To What is a Slave the Fourth of July?

Maybe more than many people think

Would forestalling or defeating the American Revolution bring about an earlier end to slavery?

Probably not. Let’s go through the evidence in turn.

Northern Slavery without the Revolution

Without the American Revolution, slavery spreads into the Midwest and declines more slowly in the Northeast.

It’s impossible to state for certain how quickly the Northeastern states would have abolished slavery in the absence of the American Revolution. We do know that precocious abolition in Massachusetts and Vermont was directly related to the events of 1776. In Massachusetts, abolition was an unintended consequence of the state’s new revolutionary constitution; in Vermont, there would be no state government at all without the Revolution. So at the very least Abolition is delayed there.

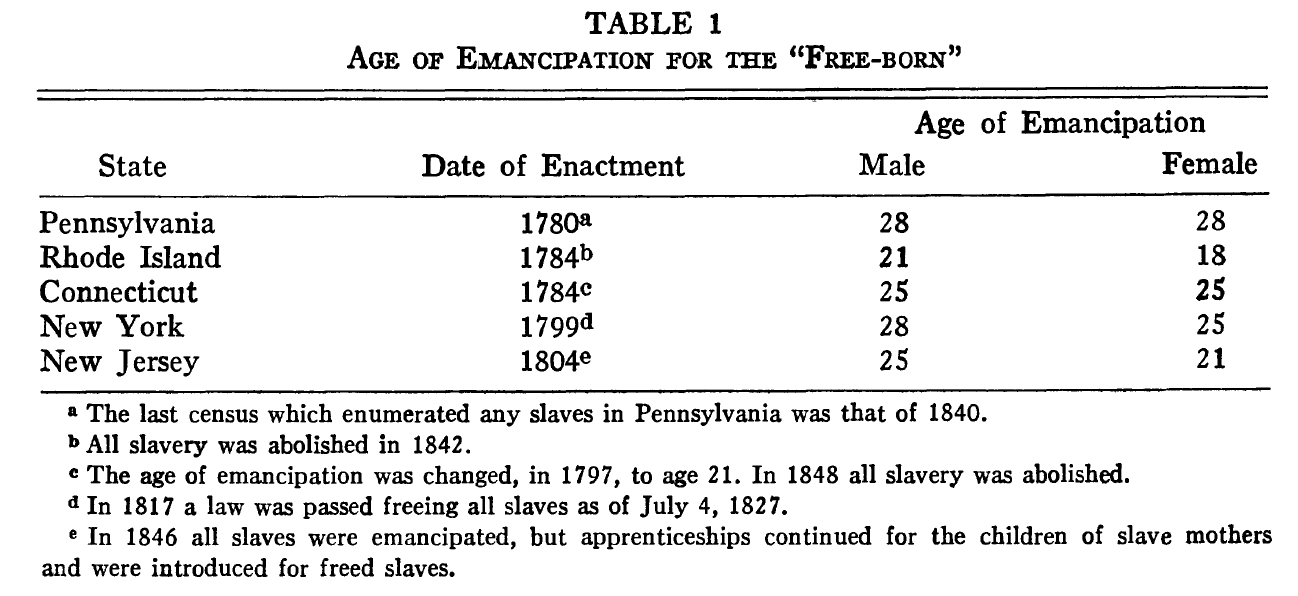

The rest of the Northeast was a lot more begrudging. None of them freed existing slaves. They did free the children of slaves born after a certain date, but only after extraordinarily long transition periods. New Jersey was the most “liberal,” freeing the children of female slaves on their 21st birthday.

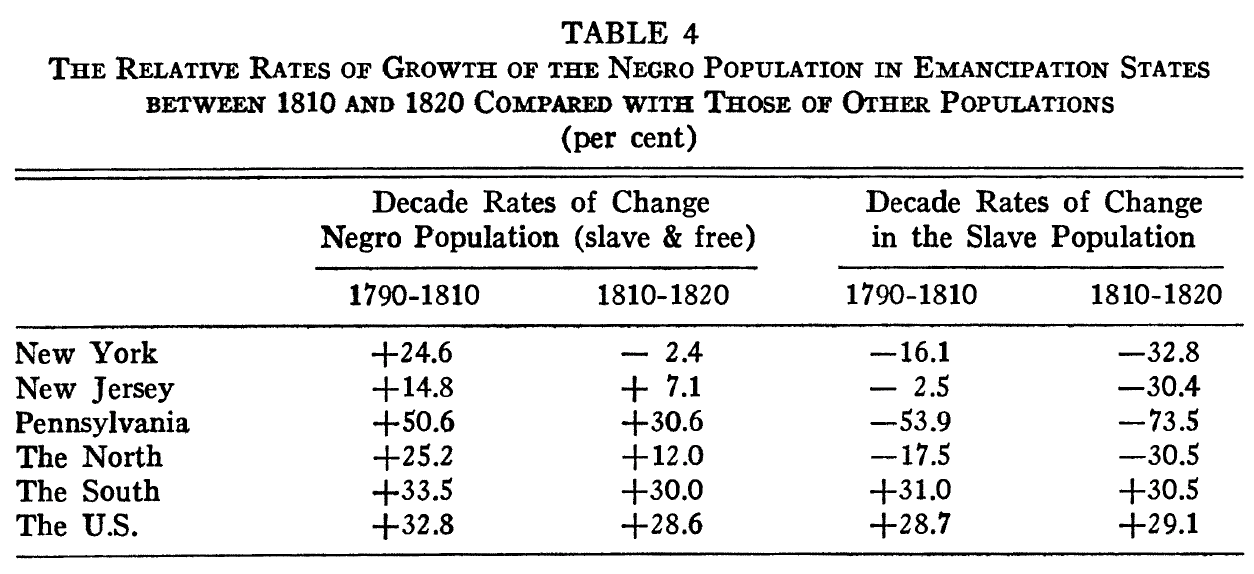

As you might imagine, that left plenty of opportunities for unscrupulous slaveowners to sell their slaves South before freedom arrived. New Jersey, at least, prohibited the forcible transportation of a free-born person out of state without their permission, but enforcement was spotty. In both New York and New Jersey, the growth of the Black population fell well below natural increase after the passage of the free-born laws and the enslaved population plummeted … even though nobody was yet legally freed.

In the words of Fogel and Engerman, “The entries in Table 4 strongly suggest that slaveholders in New Jersey were selling their slaves to the South.” It is hard to see why this sad story would be better in a world without the American Revolution.

But there are reasons to think that it would be worse. Remember, we’re in a universe where London puts imperial unity above all other interests. (If we’re not in that world, then the Revolution happens on schedule!) Well, in that world the British authorities have incentives to veto local attempts to abolish slavery. As historian David Brion Davis wrote in 1983:

If the states south of Maryland had remained within the empire, it seems highly probable that the British government would have vetoed all such emancipation acts in the interest of imperial unity and security. Restraints might even have been applied on the judges who actually succeeded in undermining slavery, without benefit of positive law, in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and the eastern provinces of Canada. Certainly British courts gave no encouragement to the idea of extending to the colonies the common-law principles of the famous Somerset case of 1772, which denied legal support for slavery in England. As late as 1827 …Somerset could not even prevent the reestablishment of slave status for a black who had voluntarily returned to the colonies from England.

Second, we have to think about the territories known in our history as “Northwest.” In 1774, the Quebec Act handed “Ohio Country” and part of “Illinois Country” over to the Province of Quebec. Slavery was legal in Quebec. Partly as a result, English-speaking settlers brought enslaved people with them. In a no-Revolution timeline either there is no Quebec Act and Virginia extends its claim, or there is one but London soon detaches the territory to accommodate English-speakers once their number rise sufficiently, just as it did in Upper Canada.

What won’t happen is a precocious ban on slavery. Abolitionist wins no victories before 1806. (That is when Parliament banned trafficking enslaved people across the imperial border.) In our world, Congress banned slavery from the Northwest Territories in 1787, but even then it required a struggle to bring Indiana and Illinois into the Union as free states. It is unlikely in the extreme that an exhausted British Crown, having recently subdued the rebellious colonies, is going to have an appetite for a similar struggle. Slavery will remain legal in the territories currently occupied by the states of Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, and Wisconsin, even if only Indiana and Illinois are likely to see a large enslaved population.

So while it is possible that abolition is delayed in the Northeast, it is probable that slavery extends into the Midwest.1

Would things be any better in a world where the Revolution happens but the British defeat it by force of arms? Not likely. Both sides promised freedom to enslaved people who fought for them but neither campaigned against slavery as an institution. Sir Henry Clinton’s Philipsburg proclamation was a worthy thing, but it was no Emancipation Proclamation. In fact, it deliberately did not promise freedom to enslaved refugees, but rather vaguely stated:

But I do most strictly forbid any person to sell or claim right over any NEGROE, the property of a rebel, who may take refuge with any part of this Army: And I do promise to every NEGROE who shall desert the rebel standard, full security to follow within these lines, any occupation which he shall think proper.

Since he hadn’t promised freedom, but rather security, Clinton saw nothing wrong with returning refugees to their enslavers when too many began escaping across British lines. Even more tragically, neither Clinton nor the British authorities saw anything wrong with re-enslaving many of the refugees themselves and transporting them to the West Indies after the war.2

The British rejected all serious proposals to attack the slave system. They summarily rejected a proposal by Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, to subdue Southern resistance with an army of 10,000 free Black soldiers. Lieutenant Colonel Archibald Campbell later proposed to free, enlist, arm, and transport at least 1400 West Indian slaves to the mainland, where they would encourage America’s enslaved population to desert and wreck the rebel economy. London rejected that as well.3 In fact, the British made open appeals to slaveholding Loyalists on the basis of their economic interests.

By the time of Yorktown, the vast majority of enslaved people were still in captivity, and the British showed no interest in freeing them.

None of this is consistent with the hypothesis that a British would have precociously weakened slavery on the mainland.

The Economics of Emancipation

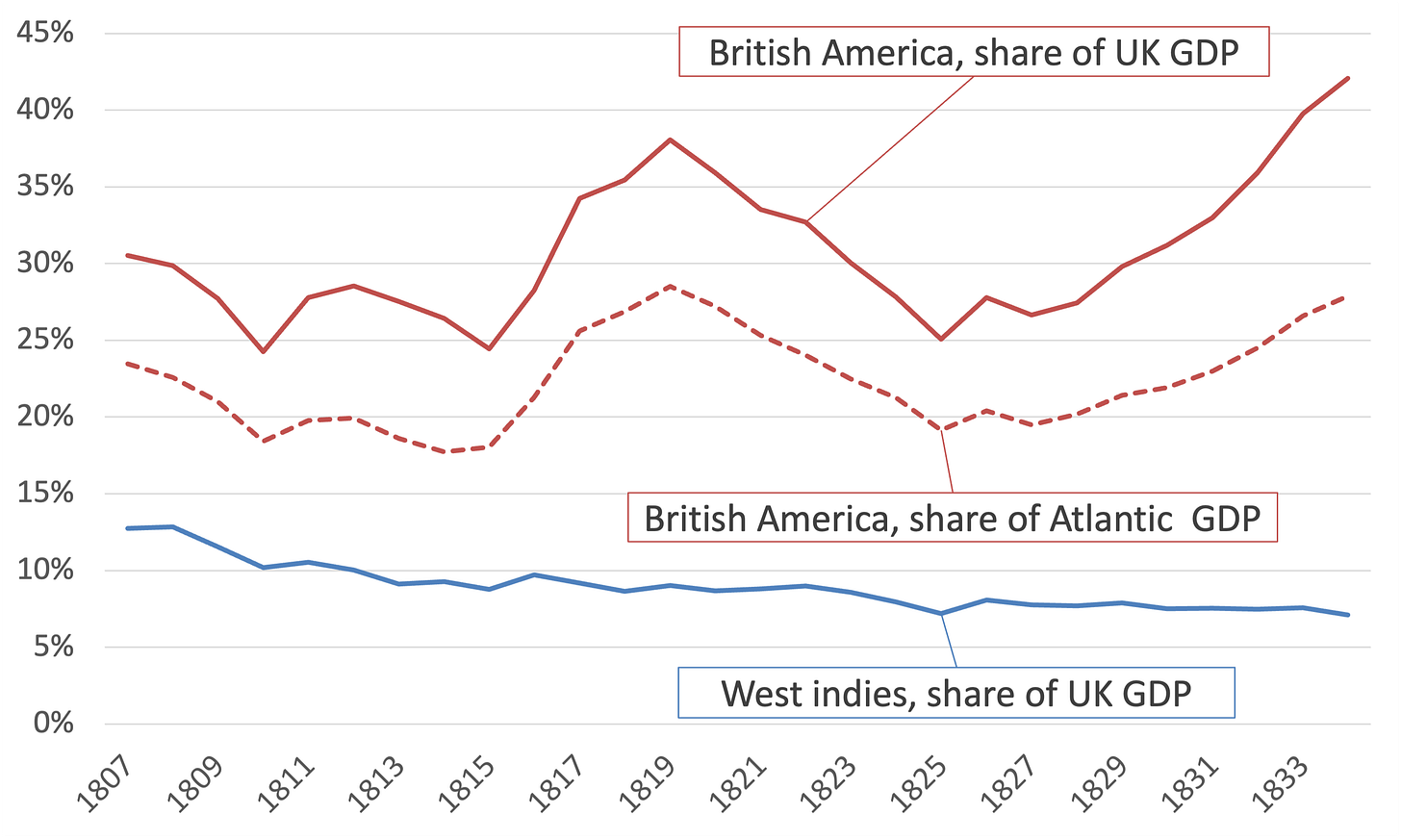

The problem is that North American slavery is on an entirely different scale from the West Indies. The “value” of the 655,000 enslaved people in the West Indies came to roughly £37 million in 1833, when Parliament passed the Abolition Act. If you add in the 2.1 million enslaved people in British North America, then you get a total value of £210 million, which is an entirely different order of magnitude. That value came to roughly 40% of the United Kingdom’s GDP. Even if you assume that Parliament could have gotten away with subsidizing the North American slaveowners to the tune of only 44% of the “market” value of their enslaved people, the cost is still 19% of the country’s GDP — and almost five times what it actually paid.

Gabriel Mathy, in his paper regretting the American Revolution, makes the point that a united empire would have a larger tax base to draw upon. That gets into two problems. One is economic and the other is political. Let’s take the economics first.

A “United Empire” isn’t that much richer than the United Kingdom

Simply put, the United Kingdom was still a lot richer than the USA in 1833, at least in aggregate terms. The nominal GDP of the U.K. was £494 million, as against £245 million for the entire United States. Adding them together reduces the scale of the problem facing any program for compensated abolition, but by rather less than you might think:

It is true that these numbers do not include Canada, but Canada was small, and they do assume that British North America grows as fast as the United States did in our history. There are many reasons to doubt that, as the last post averred. First, the colonies might not be united into a common market. Second, they might have a far less efficient financial system, in a world without Alexander Hamilton. Third, in our history there was an explosion of joint stock companies after the Revolution, as states competed with each other to charter this new form of private enterprise. Whether the reforms enabling this new form of entrepreneurialism would have spread as fast in British North America — they didn’t in Canada or the U.K. itself — without the Revolution is anyone’s guess.

How is the United Empire governed?

The political problem is fairly straightforward. Could London have taxed the colonies to pay for Abolition? Mathy’s scenario is a world where Parliament never tried to tax North America — or if it did, soon admitted that it should not. That is a strong precedent. I can imagine situations where London would ignore it — some sort of world war, for example — but I am not sure that Abolition in 1833 would have had sufficient support, even within Britain.

Alternatively, we might be in a world where the colonists accepted some sort of plan for imperial unity. Elsewhere, I have argued that this is exceedingly unlikely, but it is not outside the realm of possibility. The problem, however, is obvious: Parliament now has to deal with the representatives of Southern slaveholding elites.

Under the Galloway Plan — offered as a 1774 compromise to head off the war — the American legislature would have had a veto over British legislation for America. The 1778 offer from the Carlisle Peace Commission was far vaguer, but at the very least it would have put colonial representatives into Parliament … and it certainly appeared to preclude the possibility of imperial taxation with the words:

In short, to establish the power of the respective legislatures in each particular state, to settle its revenue, its civil and military establishment, and to exercise a perfect freedom of legislation and internal government, so that the British states throughout North America, acting with us in peace and war, under our common sovereign, may have the irrevocable enjoyment of every privilege that is short of a total separation of interest.

What would have happened had the rebellion collapsed after 1778? Maybe Britain would have been in a position to simply legislate for the colonies. But that just brings us back to the economic problem: the subsidized emancipation of slaves on the American mainland would have cost five times as much as freeing the ones in the West Indies. And no, neither Mauritius nor the Cape Colony had enough slaves to alter that conclusion.

So even if British politicians are willing to tax the colonies (risking a revolt) they would have to tax the United Kingdom quite a bit more to finance abolition.4

Cotton was a strategic crop and growing in importance

But now we get to the even bigger economic problem. Slave prices in the West Indies were sinking in the 1820s along with the price of sugar, which dropped (net of shipping costs) from 2.3p per pound in 1818 to 0.8p per pound in 1829.5 There were exceptions, of course: slavery was booming in Trinidad and British Guiana. But in general slave prices were declining across the West Indies and British policy prevented slaves in declining areas (like Jamaica) from being sold on to booming places. Barbadian slave prices, for example, fell by half between 1823 and 1831.

That is not to say that the British planters supported abolition; slavery was obviously more profitable to them than free labor would be. (J. R. Ward looked into that back in 1978.) It is to say that they were willing to accept compensation at 44% of the average market price because market prices were falling fast.

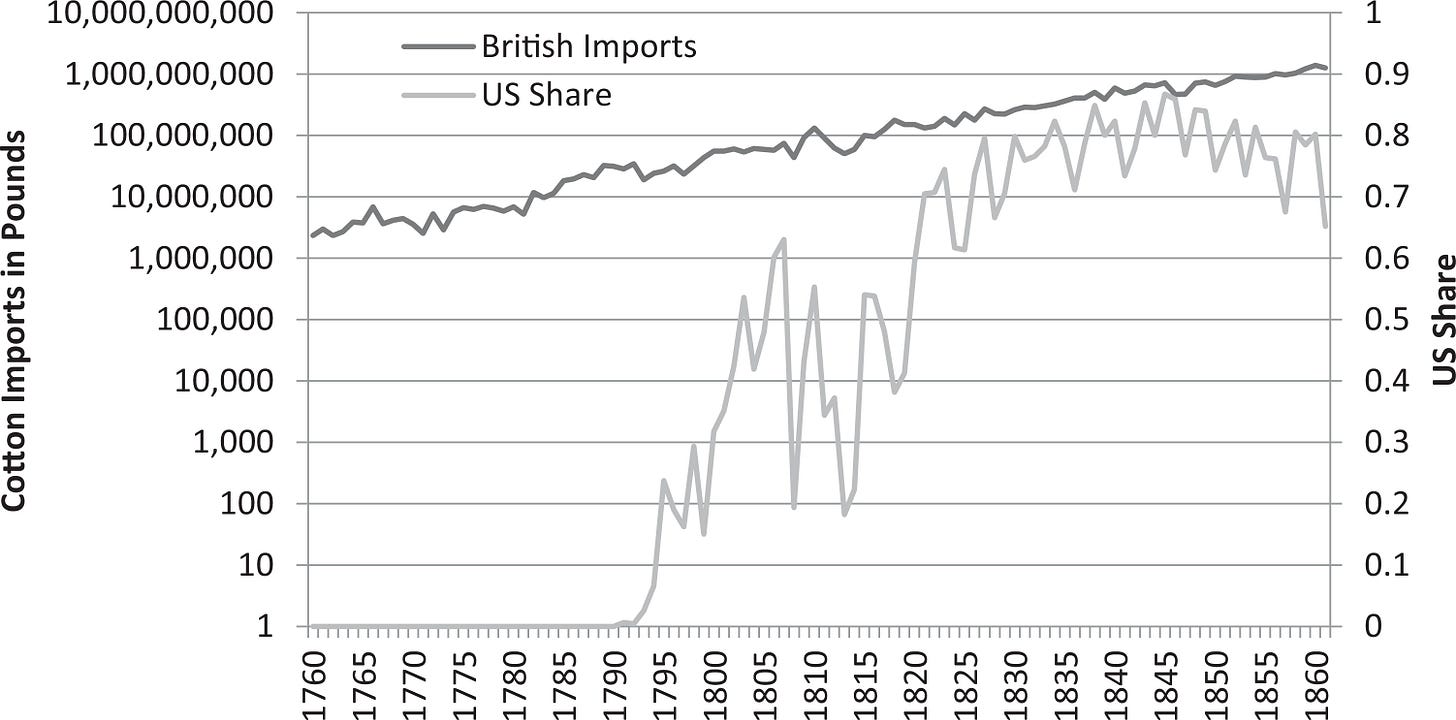

Contrast that with the southern United States, where the cotton boom was just getting started. By 1833, the South was starting a prolonged cotton boom driven by exploding British demand for cotton textiles. In addition, American slave populations were growing fast.

It doesn’t take a political scientist to realize that the politics of abolition are going to look very different in the above world. West Indian interests reluctantly capitulated to subsidized abolition; North American slaveowners are going to fight a lot harder. Any compromise is going to result in a much higher compensation per slave than the West Indian slaveowners received.

We then add the third problem: in the 1830s, cotton was a strategic crop. Sugar is nice; cotton drives the U.K. economy. It is the oil of the day. Politicians could contemplate a disruption of sugar production in the West Indies with equanimity. After all, the product is available from elsewhere and who cares if it comes from within the Empire or outside? Those same politicians could not easily contemplate a reform that might disrupt the flow of cotton to British textile mills.

In the words of David Brion Davis:

It is impossible to imagine Parliament passing the celebrated Emancipation Act of 1833 if the United States had remained part of the empire. Cotton was by then far more vital for British industry and trade than sugar had ever been. [Italics mine.]

Moreover, both contemporary British observers and later historians agree that no emancipation plan was politically feasible unless it included monetary compensation from the British government to West Indian proprietors. Parliament finally assented to the staggering figure of £20 million because of the pressing need to win the cooperation of slaveholders, to affirm the sanctity of private property, and to guard against other and more threatening forms of expropriation. But this twenty million-pound grant, which the so-called black apprentices were to supplement for a period of six years with forty-five hours of unpaid labor for their masters out of a sixty-hour working week, was clearly an upper limit for British taxpayers.

It is true that the addition of the United States would have increased the number of taxpayers, but if British leaders had managed to preserve the empire for fifty-seven additional years, they presumably would have been sensitive to American feelings about taxes. As Thomas Jefferson put it in 1824, after making somewhat similar calculations of the costs of African colonization, “it is . . . impossible to look at the enterprise a second time.”

Moral pressure mattered, but it was never sufficient on its own. Religious abolitionists like Wilberforce succeeded only by aligning with economic and political interests already in motion.

An abolitionist U.K. government will face a Hobson’s choice. They can abolish with insufficient compensation. But even if it could get such a bill through Parliament — which is unlikely — they would risk triggering a revolt by Southern planters. The British Empire could probably win such a revolt (strangling Southern commerce and trying to mobilize Northern armies), but no government would take such a threat lightly. Remember, uncompensated emancipation was never seriously contemplated in Britain; even the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 required substantial compromise and freeing slaves without compensation was seen as a radical threat to property rights.

Moreover, unless this world saw some sort of parallel to the Napoleonic Wars, Northern armies won’t necessarily be loyal to London without the national and ideological sentiment forged by the Revolution.

They can abolish with sufficient compensation — which would be extremely expensive and would still risk triggering a planters’ revolt regardless of how the resulting debt burden is apportioned. Or they can ignore public opinion (10% of the British population signed an anti-slavery petition) and hope the problem goes away.

The problem is that the longer Parliament waits, the less tractable the problem becomes. I would like to believe that a unified British Empire could solve it without having to fight against a “Treasonous Slave-Owner’s Rebellion.” But the only solution on offer parallels the kind of abolition offered in our world by the State of New York or the Province of Upper Canada: slow intergenerational abolition with ridiculously long lead-times. That is better than a rebellion, I suppose — I am genuinely not sure that is true — but it does not lead to much earlier freedom than arrived in our universe.

To give credit where it is due, Gavin Wright made this exact argument about the Northwest Territories in his 2003 essay, “The Role of Nationhood in the Economic Development of the USA,” published in Alice Teichova, and Herbert Matis (eds.), Nation, State and the Economy in History (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World (Oxford University Press, 2006), page 151.

Davis, Inhuman Bondage, pp. 148-49.

I can imagine one possible solution, but it seems almost fanciful to suggest it. Perhaps Parliament could offer British North America some sort of protective tariff, the proceeds of which could be used to pay off the abolition debt. The problem with that solution is obvious: it will anger both the U.K.’s industrial exporters and the representatives of the slave South who purchase the bulk of imported goods.

Prices are contemporary, but expressed in modern decimal values. Data from Robert Martin, Statistics of the Colonies of the British Empire, 1839, Appendix p. 3.