The politics of Abolition in Britain

This started as a Fourth of July post

I started writing a Fourth of July post to argue that American independence was all around a great thing for the world, in reaction to some fun provocations from my friends Vincent Geloso and Joseph Francis. Time, of course, was limited — there were fireworks to watch!

But as I wrote, I got caught up in the details of British emancipation. (Referee reports were also involved.) So I am pulling it out as a separate post, because why not? I’m working heavily on forced labor and its effects and I may as well share some of what I’ve learned with the three people who might be interested.

The politics of Abolition

In our world, the British parliament voted to abolish slavery in 1833 and finished the process by 1838, although you will find different dates in different sources, since the actual process was as messy as we expect any British reform to be.

Abolition arrived at the end of a long political process. The East India Company got out of the business in 1772. The Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade formed in 1787. Parliament required anyone wanting to traffic slaves to obtain a permit in order to transport slaves between British territories in 1806. That same year the cabinet restricted the transportation of slaves from other parts of the British Empire to the newly-acquired territories of Guyana and Trinidad and an act banning the slave trade passed the Commons but was killed in the Lords.1

In 1807, Parliament abolished trafficking in slaves from outside the British Empire to any point within. In 1811, it upgraded slave trafficking over the imperial border to a felony. In 1817 and 1818 the government signed treaties with the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain to further restrict the transatlantic slave trade. In 1819 it passed the innocuous-sounding Registry Act, which required every slave and slave-related transaction to be registered with the colonial government. Sounds boring, but proponents and opponents recognized that the bill intended to combat illegal slave trading and create the records that would be needed to abolish slavery in the future.2

In 1823, it banned intercolonial slave trafficking: it would no longer be legal to forcibly remove slaves from their home island (Eltis 1972). After that, British legislators actively debated slavery in almost every session — although until 1832, in the words of Izhak Gross:

Most of the governmental measures on colonial slavery were to a great extent tactical devices intended to create the illusion that ministers were pursuing an active amelioration policy and thus to prevent or reduce any pressure for more direct action (Gross 1980).

Even if much of the activity was intended to head off serious action, the fact that British governments needed to address the issue was a sea change.

Was it changing values?

What explains the increasing salience of abolition in British politics? One hypothesis is that urbanization and industrialization changed people’s values. In a nicely done 2023 paper, Valentín Figueroa (Católica de Chile) and Vasiliki Fouka (Stanford) showed that “industrialising parishes sent more abolitionist petitions than other parishes.”

I would prefer to attribute changing values to the American Revolution, but sadly, that’s not right. Figueroa and Fouka failed to recognize that America fought a war not to abolish slavery but for the freedom to write “industrializing” with a Z, which we call “zee,” not “zed.”

The correlation between abolitionist sentiment and industrialization is only suggestive. But Figueroa and Fouka also manage to track down the only surviving copy of the myriad anti-slavery petitions that hit Parliament, link the names to data on individual occupations from the Manchester and Lancaster Family History Society, and show that people involved in manufacturing were much more likely to sign.

They are on weaker ground when they argue that the new industrial elites had distinct moral values, although they convincingly show that industrialization seems to have something to do with the shift in popular opinion.

Was it slave resistance?

A second hypothesis is that the slaves themselves pushed along their own liberation. Maybe rising unrest in the West Indies pushed people in Britain — including slaveowners — to see the writing on the wall? In 1816, Barbados experienced the largest slave rebellion in its history. The massive and (mostly) nonviolent Demerara Rebellion broke out in 1823 — suggestively, this is also the year Parliament began an almost continuous debate on slavery. In 1831, the Jamaican Baptist War started on Christmas Day as a general strike and soon descended into generalized violence that killed 14 white people and at least 207 rebels.

Speaking as someone who almost named one of his children after Denmark Vesey, a great American, it would certainly be nice to believe that the enslaved were the authors of their own emancipation. In a current working paper, the excellent Gabriel Leon-Ablan (King’s College London) tries to make the case that the revolts were key to the passage of the 1833 act. Unfortunately, I don’t quite think he succeeds.

The standard story is that abolition moved to the front-burner because the Great Reform Act of 1832 expanded the electorate and made Commons representation more proportional to population. Leon Alban makes the argument that it was actually slave revolts, particularly the aforementioned 1831 Baptist War. The argument is that the rising cost of control — and the rising chance of losing everything in a successful revolt — reduced the profitability of slavery. That in turn caused MPs from constituencies with lots of slave owners to shift towards abolition. Moreover, Leon-Alban argues that the effect was cumulative: each slave revolt raised planter expectations that there would be future slave revolts.

It’s not implausible, but the evidence is thin. The basic model examines whether representatives from constituencies that were more exposed to slave revolts were more likely to vote for abolition — with exposure measured as the number of slaveowners in a Parliamentary district who owned slaves in a colony that experienced a revolt in 1823-32. He also runs a difference-in-difference model looking at how much constituents’ economic exposure to the Baptist War correlates with the likelihood that an MP switched his vote from against a 1826 resolution condemning the harsh treatment of Jamaican rebels to support for one of several the 1833 procedural votes on the abolition bill. (The bill itself passed by acclamation.)

But there are issues:

Everyone experiences the Baptist War “treatment”! There’s only one pre- and post-shock. That makes diff-in-diff with time and group fixed effects fragile.

There’s no falsification test. What happens if you placebo the revolt year to 1829 or 1830?

The exposure variables are coarse and arguably endogenous. It is quite plausible that the number of slaveowners in a constituency correlates with something else.

Standard errors are clustered at the MP level, but the sample isn’t huge. How much is driven by a handful of Whigs switching sides?

The coefficients aren’t that large, and given that abolition passed by acclamation, it is a little hard to believe that the slave revolts really mattered to the timing or the passage.

Finally, there is that evil bugaboo of all empirical economics: endogeneity. The outbreak of the Baptist War was not separate from the debate on abolition. The rebels were highly connected to the abolitionist movement; their initial plan was a general strike, but things spiralled out of control.

The paper cites newspaper reactions, mentions of the rebellion in parliamentary debates, and public reports from the Colonial Office. But there is no smoking gun — no memo from a swing-vote MP saying “I’ve changed my mind because of the Baptist War,” no diary entry from Stanley or Howick citing the revolt as decisive. Instead the evidence is circumstantial. The timeline lines up, the tone of debate shifts, the Abolition Act follows within 18 months.

But abolition had been in motion for years and the Reform Act had just gutted rotten boroughs and practically doubled the electorate!

The story isn’t implausible — William Knibb testified evocatively about the rebellion in front of a Parliamentary select committee — but it remains unproven.

The compensation debate

Basically nobody in the 1830s thought that it would be a good idea to simply abolish slavery without compensating the slaveowners — even John Stuart Mill thought former slaveowners should get something.3 There were examples of abolition without cash payments from North America: eight American states and two British Canadian provinces abolished slavery between 1777 and 1804. None of them paid the former slaveowners a dime.

The problem was that most of the emancipation schemes adopted by those states provided for extraordinarily long transitions. Only Vermont and Massachusetts freed existing slaves — and in Massachusetts that happened because of a decision by the Supreme Judicial Court that declared forced labor incompatible with the Commonwealth’s constitution, not legislative action.

The remaining jurisdictions not only kept existing slaves in bondage for the rest of their lives, they kept the first generation of free-born in thrall for astonishing long periods: from 18 years for a female child born in Rhode Island all the way up to an astonishing (and horrifying) 28 years for a male child born in Pennsylvania.4 Upper Canada’s freedom statute was similar, enslaving the next generation for the first 25 years of their lives. Two jurisdictions got around to completely abolishing slavery before 1833 — New York and Upper Canada — but it took 18 years in New York (1799 to 1817) and 26 years in Upper Canada (1793 to 1819).5

In short, if a British legislator was going to look around for emancipation plans that didn’t come from Spanish America — as far as I know, nobody thought of the Latin countries as a model — the only radical examples came from Massachusetts and Vermont. But neither had significant enslaved populations at emancipation. So nobody save a few powerless radicals considered the idea of just doing away with forced labor.

Instead, the question became: how much it would take to buy off planter opposition?

The plan

Of course, when the government made its initial abolition proposal on May 14th, 1833, it didn’t phrase it in such crass terms.6 It proposed the following plan:

All children under six would be immediately freed;

Slaveowners would continue to provide for their former slaves’ subsistence during the 12 year period;

The government and the slaveowners would fix a notional wage rate for the former slaves (based on the value of the slave) — the former slaves would then have to continue working for 12 years for the same slaveowner as before;

The government would take out a £15 million loan that would be lent to the former slaves in order to purchase their own manumission;

The “apprentice” would not actually get any wages. The former slaveowner would retain 75% and the remaining quarter would be used to repay the £15 million loan over the 12-year phase-out period;

The imperial government would subsidize West Indian expenditures on judges, police, and education in the colonies, although no amount was set. The idea was twofold. First, it would help buy off colonial resistance. Second, it remove power from the slaveowners by selected officials “to be appointed by the Crown, unconnected with the colonies, having no local or personal prejudices, paid by this country, for the purpose of doing justice between the negro and the planter, of watching over the negro in his state of new-born freedom, and of guiding and assisting his inexperience in the contracts into which he may enter with his employer.”

Now, twelve more years of service is a hell of a benefit for the slaveowner! It is not implausible, in fact, that 12 years exceeded the average expected future work life of most adult slaves.

The government plan percolated for a while but did not sit well with either abolitionists or slaveowners. On July 3rd, 1833, a Tory MP from Liverpool named Dudley Ryder (aka “Lord Sandon,” from his status as the heir to the Earldom of Harrowby) invited a bunch of MPs from the “West-India body” to his house that morning. There they hashed out the £20 million figure. Later that day, Ryder gave a Commons speech proposing that the government just take out a £20 million loan and just give the cash straight to the slaveowners. In the same speech, he warned the slave lobby that if they tried to get more, they would fail and abolition would happen regardless.7

Ryder came up with a bizarre formula to justify his valuation. First, he claimed that the value of the “whole of the produce of the West Indies” came to £6.1 million. One-quarter of that — the share of labor output that the government bill would have notionally redirected to paying for manumission — was about £1.5 million. Over 12 years that came to £18 million. Throw in “a couple of millions” and you got £20 million.

Everyone knew that Ryder’s formula was gobbledygook based on invented data and that the number was a political compromise, even if nobody wanted to say so explicitly. Well, nobody save a Whig parliamentarian, Ralph Bernal, who admitted that the figure “was proposed rather for the purpose of conciliating the colonists, in order to induce them to act cordially with Government, than as a compensation for the loss that might be sustained.”8

Interestingly, the only reference to the market value of slaves came from the abolitionist John Spencer, aka Lord Althorp, who said that even though the value of the West Indian “property” came to £45 million, he “considered £15 million quite sufficient,” because they were going to be entitled to free labor for some time thereafter.9 How Lord Althorp came up with the £45 million number in 1833, before the Slave Compensation Commission started work, is thoroughly unclear.

Parliament finally passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833 . The act set emancipation day as August 1st, 1834, but provided for “apprenticeships” thereafter: four years for domestic slaves and six years for field hands.10 Colonies with some degree of self-government could accelerate that process: Antigua and Bermuda emancipated all the enslaved immediately and Jamaica voted to limit all “apprenticeships” to four years.11 Parliament quickly came under pressure to abolish the “apprenceships,” however, and in May 1838 it voted that all former slaves shall be freed completely and totally on August 1, 1838, except for Mauritius, where freedom arrived on March 31st, 1839.12

What value to a Slave is the First of August?

Divvying up the £20 million proved a little more complicated. The Slave Compensation Commission collected a database of 74,000 transactions recorded between 1822 and 1830. This data collection tour-de-force valued the stock of slaves across the Empire at £45 million.

The Abolition Act of 1833 and Slave Compensation Act of 1837, however, authorized the use of only £20 million in bonds to pay off the slaveholders, not £45 million.13 So the Commission did its best to divvy up the money proportionally to the “market” value of the slaves. The end result was that the average slaveholder received 44% of the calculated market value in compensation. That is better than giving them 100%, of course, but worse than zero. Moreover, it doesn’t account for the fact that slaveowners also received four years of free labor in addition to the compensation payments.

In 1974, Fogel and Engerman calculated that the value of the additional years of labor came to an additional 47% of the market value … although they assumed that the former slaves were forced to work for their former owners for six years and handed over only 75% of their output. In reality, the system lasted only four years and the “apprentices” engaged in widespread wildcat strikes, legal actions (using their newfound rights), and passive resistance.14

Still, the calculation gives an idea of the political possibilities: the British voted for freedom, but they also voted for a subsidy to enslavers intended to compensate them for more than 90% of the value of the labor they could steal from their slaves.

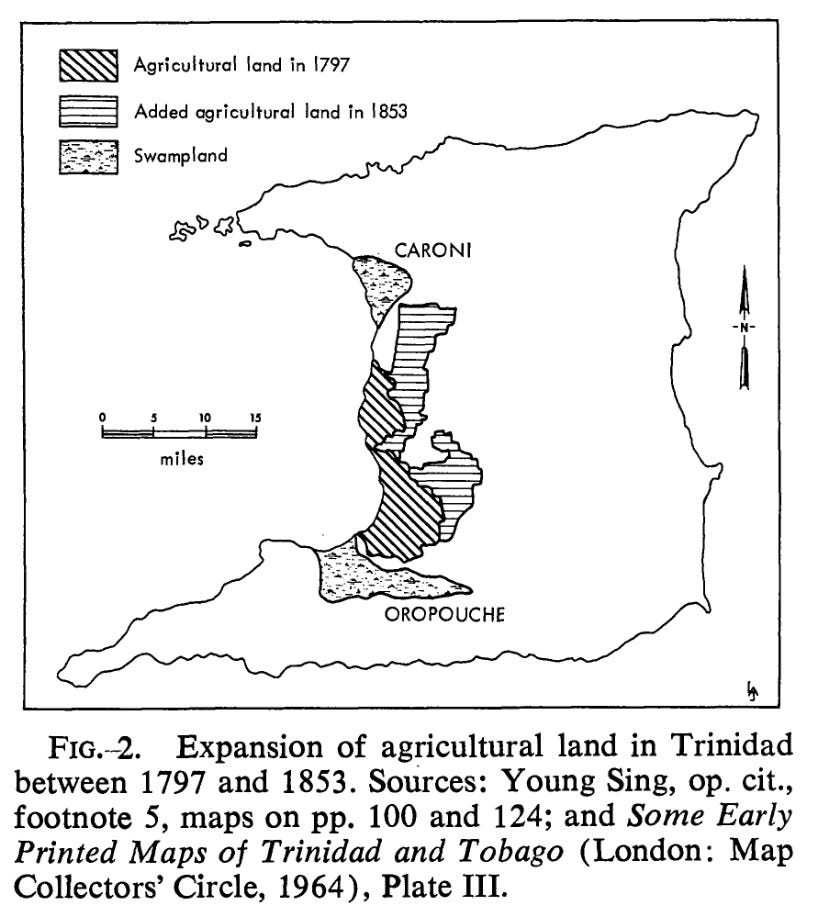

In addition, the price data show just how badly the older slave economies of the West Indies were performing by the 1830s. Slave prices were high in Guiana, Trinidad, and British Honduras — places to which London restricted slaveowners from forcibly transporting their slaves. Elsewhere, save South Africa and Mauritius (neither in the West Indies) prices were generally low and falling.

Financing the subsidy

The subsidy Parliament granted former slaveowners was significant. The £18.7 million that the country ultimately shelled out came to 4.1% of GDP. In 2024, that would come to about £116 billion: call it, say, roughly equivalent to the current plan the to replace the United Kingdom’s nuclear deterrent with new submarines, warheads, and delivery systems.

Still, in the context of the U.K.’s national debt at the time, it’s not that large an effort. The debt hangover from the Napoleonic Wars came to £754 million — making the cost of paying off the slaveowners a 2.5% drop in a rather large bucket. The bond issue attracted a lot of attention since it was the first major borrowing since the end of the wars. But by this point the British financial machine was in fine fettle. The Treasury announced that it would allow open bidding, four investor groups announced their desire to bid, but for some reason three of the four groups dropped out. Rothschild wound up financing the entire issue, but that didn’t have much effect on its success: the effective interest rate on the first £15 million issue in 1835 came to only 3.375%. Interest expenditures on the new debt came to a little over 1% of all government spending.

The bottom line is that the British government really wasn’t willing to spend very much directly on abolishing slavery. Moreover, sugar was not particularly important to the British economy. It wasn’t a strategic good and there were plenty of other places from which it could be imported. As a result, nobody worried about the inevitable economic disruptions that would come from the end of forced labor.

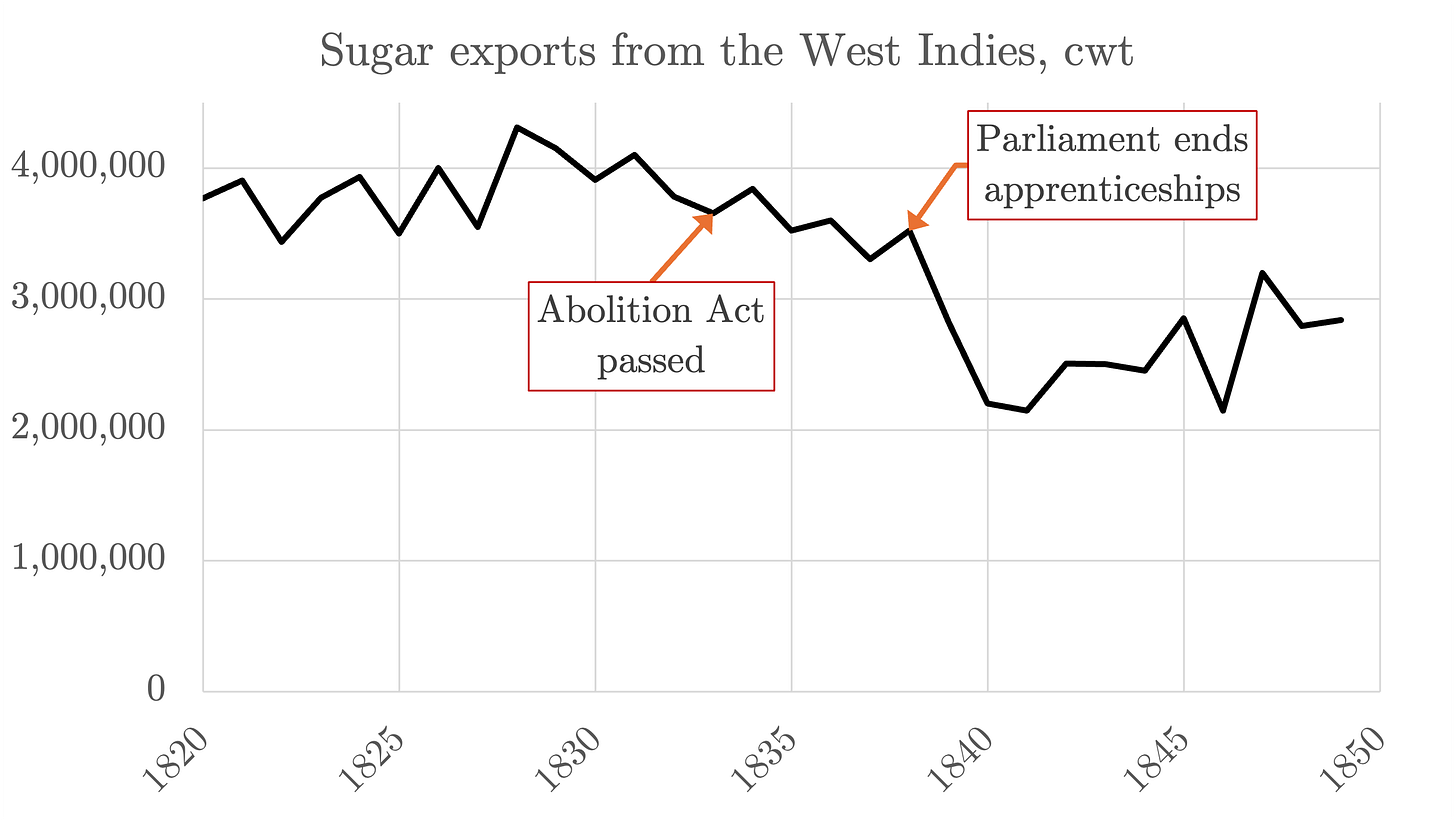

Why did emancipation cause sugar production to crash? Well, forced labor in the sugar fields was forced. Take away violent coercion and allow workers to chose their employment, and the labor supply for sugar inevitably falls.

How much the labor supply for sugar fell, however, depended on the particulars of the island. Stanley Engerman usefully broke the West Indies into three groups:15

The small overpopulated islands of Antigua, Barbados, and St. Kitts. In those islands the former slaves simply lacked outside options. There was not a lot of free land to settle and few alternative economic activities. In those places, working conditions for freedmen certainly improved, but generally things went on. In the decade after emancipation sugar output rose 9%, 6%, and 4%, respectively. Per capita output also rose.

The frontier economies of Trinidad and Guiana. There newly freed slaves lit out for open lands as quickly as they could. This prompted two adjustments. First, the governments of the colonies tried to stop the freedmen from settling the frontier. Second, they started to import indentured laborers from India in large numbers. In Trinidad the combination “worked” and sugar production rose 22%.16 In Guiana, with its huge open frontier, the strategy failed: production collapsed by 43%. It is worth noting that per capita production declined in Trinidad — it was only a huge influx of Indian laborers that enabled production to expand.

The middling colonies. These were places that lacked Trinidad and Guiana’s endowment of potential sugar lands, but which also had plenty of places for freedmen to go and plenty of alternate economic activities for them to engage in, from subsistence agriculture to logwood to bananas. In most of these places, sugar output plunged by about half, with only Dominica and St. Lucia experiencing smaller declines (6% and 22%, respectively).

But sugar was a sideshow and London didn’t really worry about the impact on production in 1833. There were Parliamentary inquiries into the causes of the decline in 1842 and 1847-48, but the tone was more forensic than urgent.

The bottom line

Abolitionist sentiment grew in Britain throughout the beginning of the 19th century. Whatever the trigger — insurrection or industrialization — the Representation of the People Act of 1832 made abolition inevitable.

The Britain of 1833 deserves acknowledgement for abolition. It wasn’t inevitable or easy. But it is important to note two things. First, nobody was willing to simply throw the slaveowners under the bus. That would have been the just thing to do, but the belief that enslavement was a “property right” for the enslaver ran deep.

Second, the sacrifice was small, almost risible, and certainly unnoticeable to the great bulk of Britons — about 1% of contemporary government spending. In fact, it also was unnoticeable to the vast majority of the British elite, which had no interest in West Indian or Mauritian sugar production, let alone whatever it was that the Cape Colony did with its enslaved population. A fall in sugar production would be a minor political headache at most, since sugar was readily available elsewhere.

Needless to say, the second point did not hold for most of the other places around the world that allowed chattel slavery in the 1830s.

Abolition was a great event, but it is far from clear that it would have happened had the impact on British purses or British production been even a little bit higher.

The law limited the transportation of enslaved people into the territories of Demerara, Essequibo, Berbice (later combined into British Guiana) and Trinidad to 3% of the current enslaved population. Governors could restrict the number of permits further if they so desired. See D. Eltis, “The Traffic in Slaves between the British West Indian Colonies, 1807-1833,” The Economic History Review (February 1972), pp. 55-64.

Hansard, “Slave-Registry Bill,” Volume 40, debated on Tuesday 8 June 1819. A registry would only be necessary, of course, if the government intended to abolish slavery alongside some sort of compensation for the slavers.

Mill expressed outrage in 1833 that Parliament did not immediately free the slaves if it was going to pay full market price for them, but in the same paragraph he dismissed the idea of emancipation without compensation:

On the best official calculations which could be made, the twenty millions which have been granted are, as nearly as can be estimated, the FULL MARKET PRICE of all the slaves in our colonies. Emancipation without compensation was apprehended; but who ever dreamed that the gift of a reformed Parliament would be compensation without emancipation; that England would buy the slaves out and out, and not make them free!

Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman, “Philanthropy at Bargain Prices: Notes on the Economics of Gradual Emancipation,” The Journal of Legal Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2 (June 1974): 377-401, Table 1.

See Fogel and Engerman (1974). The rapid decline in the enslaved populations of New York and New Jersey horrifyingly implies that plenty of slaveowners sold their slaves South long before the law would free them.

Hansard, “Ministerial Plan For The Abolition Of Slavery,” Volume 17, debated on Tuesday 14 May 1833.

Hansard, “Ministerial Plan For The Abolition Of Slavery,” Volume 18, debated on Monday 3 June 1833.

Hansard, “Ministerial Plan For The Abolition Of Slavery,” Volume 19, debated on Monday 22 July 1833.

Hansard, “Ministerial Plan For The Abolition Of Slavery,” Volume 18, debated on Monday 3 June 1833.

You can find the details at Hansard, “Abolition Of Slavery,” volume 42, debated on March 29, 1838, where Parliament discussed the end of the “apprenticeships.” Confusingly for a modern reader, the parliamentarians refer to field hands as “prædial” apprentices and domestic slaves as “non-prædial.”

Kate Boehme, Peter Mitchell, and Alan Lester, “Reforming Everywhere and All at Once: Transitioning to Free Labor across the British Empire, 1837–1838,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 2018; 60(3):688–718, p. 711.

Boehme, Mitchell, and Lester, p. 715.

The U.K. issued £15 million in new debt in 1833 to pay off slaveowners in the West Indies. The 1837 act cobbled together a portfolio of existing bonds held by the Exchequer or the Bank of England to provide another £5 million to free slaves in the rest of the Empire. See Michael Anson and Michael D. Bennett, “The collection of slavery compensation, 1835–43,” Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 1006 (November 2022), p. 4.

Gad Heuman, “The Apprenticeship System in the Caribbean,” New West Indian Guide (22 Aug 2023).

Stanley Engerman, “Economic Adjustments to Emancipation in the United States and British West Indies,” The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Autumn 1982), pp. 191-220.

The Trinidadian colonial government didn’t fully open the island’s Crown Lands to small-scale settlement until 1869. (See National Archives, Honoring Our Industrial Roots.) This is particularly awful considering as they consisted of more than four-fifths of the island’s land area. From Bonham C. Richardson, “Livelihood in Rural Trinidad in 1900,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers, Vol. 65, No. 2 (June 1975), pp. 240-251: