The intervention will be televised

You will know if the U.S. is planning to invade Venezuela

There is a lot of worry out there that the United States might invade Venezuela. The consensus among commentators is no, they won’t, but there’s always a degree of tea-leaf reading in the analyses.

I am here to say no tea leaf readings are necessary. Venezuela is hard to invade, so you’ll know it if an invasion is in the works. But to my surprise, there was no easy place to find an estimate of what it would take to invade or why it would be obvious!

So I decided to fill the gap. I’m not a military analyst. In the Army, I was just a lowly enlisted guy in the S-2 of what was then called a corps support battalion. But I read a lot in the course of putting together all the paperwork for a Navy commission that I never pulled the trigger on, and I read even more when bored in New Jersey and Afghanistan. I even wrote “A Historical Guide to Invading Panama,” based on a bunch of research I did while writing The Empire Trap. So if not me, who?

I’ll start with the requirements for “forced entry” and discuss what observers would see if that were in the works. Then I’ll mention “kinetic” actions that would likely precede the forcible entry.1 Finally, I’ll show how anyone who cares will see the preparations coming a mile away. Think of it as three phases: lodgment, air supremacy, and sustainment.

The U.S. could suddenly airstrike Venezuela or land some sort of small team, of course. We could even try a raid using the Marines currently offshore. But that’s another way of saying that the U.S. could do something completely stupid, and you can’t predict stupid. (When I do stupid things, I’m usually surprised at myself.)

But if invading Venezuela is going to be less than 100% stupid, it will look like what I’m laying out below. And you will see it coming well before the fact.

Pier review (lodgment)

Venezuela has two airfields conveniently located on the coast: Simón Bolívar, in Maiquetía, right over a rather intimidating set of low mountains from Caracas, and Jose Antonio Anzoategui International Airport in Barcelona, located a hair less than 200 miles from Caracas. Both also happen to be bases for the “Bolivarian Military Aviation of Venezuela.”2

Now, the U.S. wouldn’t need to seize the airfields, as helpful as that might be. The mellifluously-named “Joint Concept for Entry Operations” points out that sea-basing is a reasonable substitute for land basing. Right after entry forces secure a lodgment, follow-up reinforcing entry forces will be tasked with creating expeditionary airfields and securing temporary docks to allow offloading.

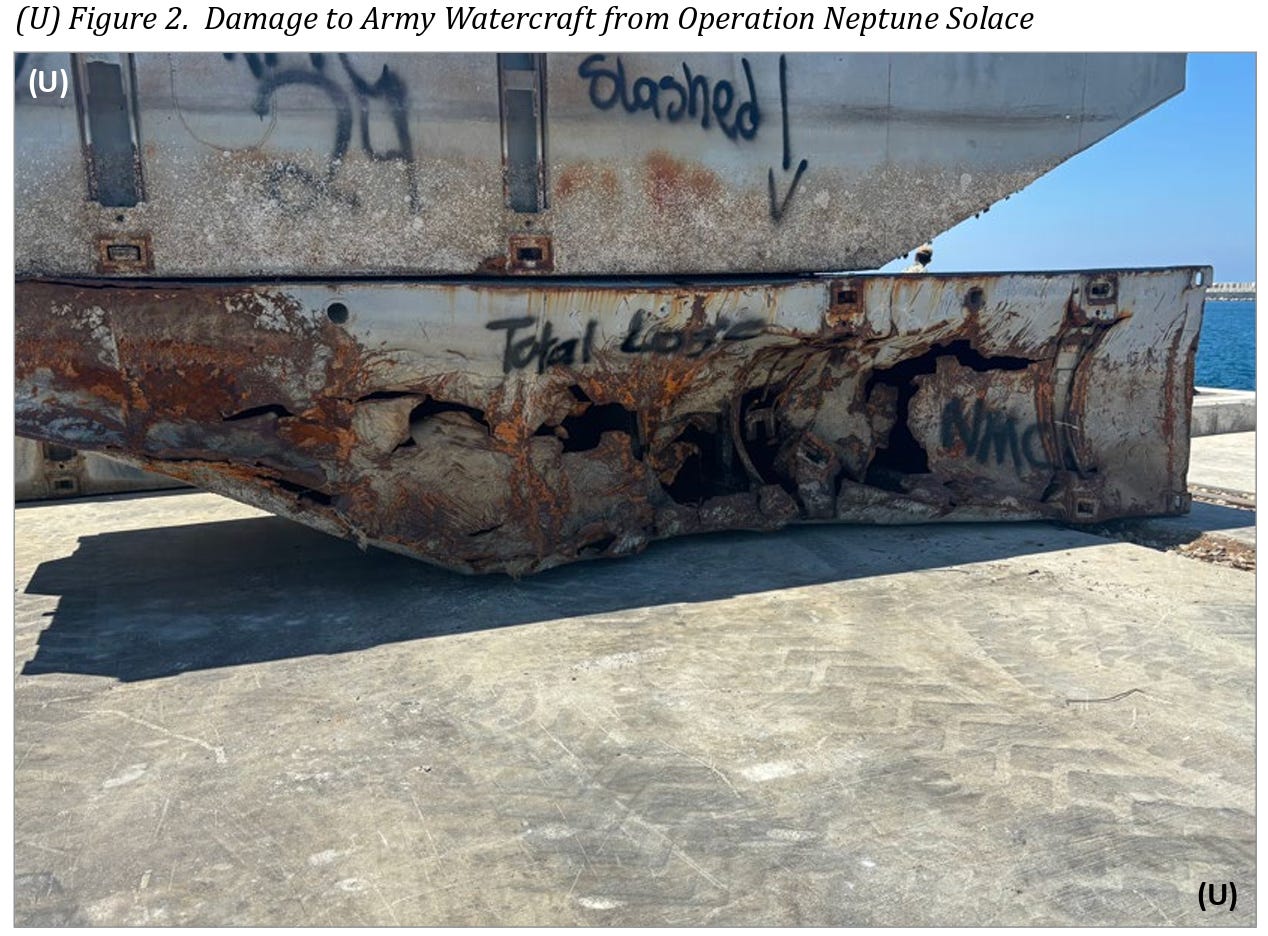

That said, the fiasco of the U.S. floating dock — in Army-speak the “joint logistics over-the-shore” (JLOTS) infrastructure — in Gaza last year should give a little pause as to the military’s ability to pull off this sort of thing seamlessly, let alone without giving notice something was up.3 And while the military could get an airfield up-and-running in 96 hours if it had to, they probably would prefer not to.

Either way, the U.S. needs to get a secure lodgment before it starts worrying about JLOTS and managing captured airfields. That means a force package of at least one Marine Expeditionary Brigade (MEB) and an airborne brigade from the Army. That’s about 14,500 marines and about 4,000 soldiers. The rationale here is that Venezuela has a pretty big military, if a flabby one of uncertain capability and morale.4 Without the MEB, airborne operations will fail if Venezuelan counterattacks exceed the brigade’s defensive capacity. (That went kind of badly for the Russians in 2022.)

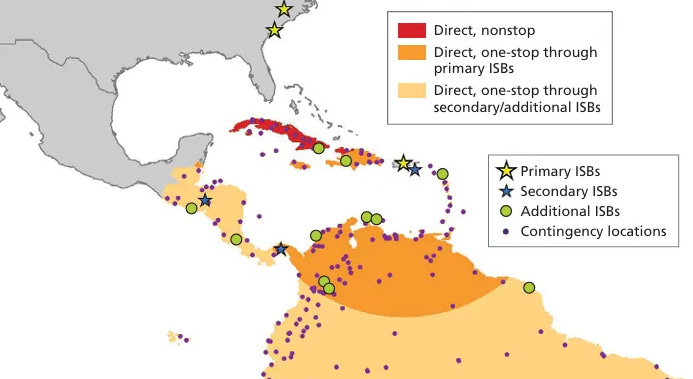

Landing a MEB requires about 15 specialized amphibious warfare vessels. (Page 6.)5 As of right now, we have only three amphibious warfare ships in the Caribbean: Iwo Jima, San Antonio, and Fort Lauderdale. (The latter name makes me smile, I can’t help it.) The remaining ships are scattered from Japan to Virginia. It would take about 20 days for the vessels based in Sasebo and Okinawa to get to the Caribbean, so that’s the first thing to watch for.

I suspect that U.S. planners would prefer to go larger, but we can’t. In theory, we have the capability to land two MEBs. In practice, it’s only one, because only 41% of our amphibious fleet is fully operational at any given time. (That is doubleplusungood.) On the other hand, we can get airborne units into the mix, so it is likely that the 82nd Airborne would stage simultaneously with the MEB. The Army and Air Force can deploy one brigade of approximately 3,000 to 4,000 reinforcements somewhere between 18 and 37 hours after notification (page 25 and 27). It takes about five hours to fly from North Carolina, but the operation would likely stage through Puerto Rico.

Bomb Voyage (air supremacy)

None of this will work without air superiority, and preferably air supremacy. So the U.S. will want to dismantle Venezuela’s air force and air defenses as well as degrade the of the Bolivarian Armed Forces to call up and move around their forces. So the United States will open with a massive focused bombardment that won’t stop until there are no more SAMs and all Bolivarian Military Aviation is stopped. Israel’s success in destroying Iran’s air defense system implies that this won’t be that hard, but it will be dramatic.

It is hard to imagine the United States carrying out such a campaign without an aircraft carrier. In theory it could — Venezuela isn’t that far away. But in practice it probably won’t. Air operations are split into offensive counter air (OCA), suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD), and defensive counter air (DCA), all of which are easier to manage with the flexibility you get from having a carrier right offshore.

So the first thing to look for is a carrier group in the Caribbean. Again, to be clear, the U.S. might try to launch an air campaign without one — it’s just not the way I’d bet. The main reason to avoid moving a carrier to the Caribbean is to preserve the element of surprise but you need to move the amphibious fleet anyway. In addition, there isn’t a whole lot that the Venezuelans can do with advance knowledge, except maybe crater their own air bases’ runways. Which won’t work even if they tried: the USAF plans on getting a 10,000-foot runway back up and running in 6½ hours.

Even without a carrier, you would see a lot of Air Force tankers start flying in predictable patterns off the Venezuelan coast. Tanker aircraft don’t randomly float around or wait on the ground until they’re needed; they fly along set routes (called “tracks” or “anchors”) so that planes needing fuel can rendezvous with them safely and efficiently. (See page 18.) In the run-up to a big strike you will see multiple tankers on overlapping flight paths making frequent trips in and out of the same zones.

Hurry up and wait (sustainment)

Before we finish, let’s circle back to what happens after the U.S. takes control of an airfield or establishes a lodgment to bring in forces by sea. What happens is that somewhere between 50,000 and 100,000 uniformed personnel from every service save the Space Force (plus the associated equipment and supply) pour into Venezuela.6 These units will start arriving en masse within two or three days of the initial forced entry (page 46). I have no idea how many divisions the U.S. will move or how it will plan the invasion after the initial forced entry — I am trying to resist the temptation to start drawing MSRs on a map of Venezuela and play-acting what I used to help officers do for real — but it will be a lot.

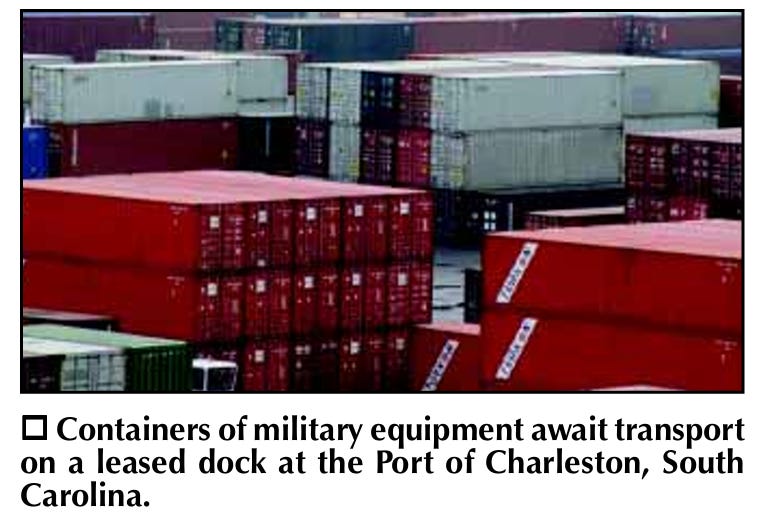

The preparations for the above are gonna be very very obvious to everyone. First all these units will get “prepare to deploy orders” (PTDO). Within a week, units will start moving towards “ports of embarkation.” Soon thereafter you’ll see heavy equipment loaded onto civilian trucks and trains; unless things have changed dramatically, you’ll see convoys on the roads. By the second week, various East Coast ports will fill up with military vehicles. (See Chapter 4.) You’ll also see increased chartered aircraft traffic as the Civil Reserve Air Fleet ramps up. By the third week, anyone looking at American ports will see ro-ros moving in and out constantly.

“Hurry up and wait” is not just an old Army cliché— although oh my Lord is it an accurate description — but it describes the reality even with modern logistical miracles. Units get PTDOs quickly, but then spend days doing the unglamorous things I spent a lot of my doing in 2002: pulling vehicles out of garages and storage lots, draining fluids for transport, signing hand receipts, filling out spreadsheets, checking off lists, and loading gear onto trucks and railcars. When you start seeing ports and airfields backed up with equipment, you’re already two weeks into a mobilization, and you know the big move is coming.

Ports and railheads have finite berths and sidings, which means units end up parked in improvised motor pools on the edges of cities, waiting their turn to load. Traffic jams happen, with civilian containers backed up waiting to hand off military cargo. During Desert Storm, nearly 48,000 containers backed up despite months of preparation. (Page 2.) That was with Cold War capacity still at hand. Today’s smaller merchant fleet and leaner port system would make backups more obvious, not less.

TLDR

The presence of electric flying robots on the battlefield will change things, of course. My intuition is that drones will continue to favor the defense, as they have in Ukraine, but that is speculative. The battlefields of 2035 may be filled with microwave rayguns that fry autonomous flying robots but allow lightly shielded grunts (or heavily shielded vehicles) to pass unmolested. Who knows? In the case of Venezuela in 2025, however, I will be very surprised if the National Bolivarian Armed Forces has either enough drones on hand or the tactical knowledge to use them effectively.

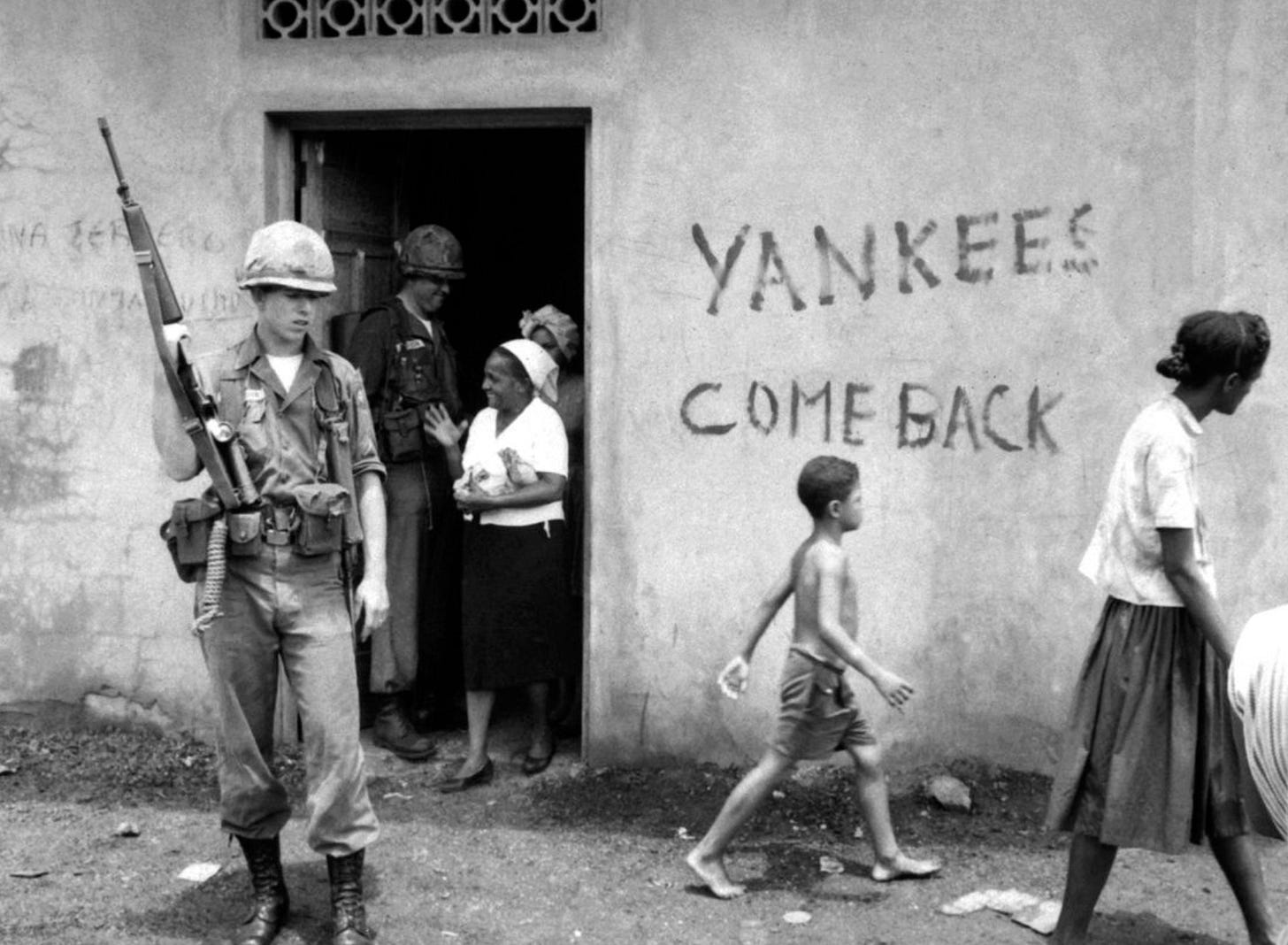

Venezuela in 2025 is not Panama in 1989 or the Dominican Republic in 1965. In Panama, the build-up in the Canal Zone was obvious if you looked — the invasion was a surprise more because too many observers lulled themselves into thinking that George H.W. Bush would never pull the trigger, not because the signs were hard to see. Meanwhile, in 1965 the D.R.’s small 18,000-person military was busy fighting itself (and the U.S. had far greater air and sea lift capacity than today) so it could take only 48 hours between giving the order and helicoptering the first Marines to the Embajador Hotel.

Venezuela won’t work like that, at least not if regime change is the point. It will require preparation. The invasion will be televised and you will all see it coming. So please ignore breathless speculation or silly news reports. In fact, please ignore reasoned measured speculation, unless the speculator has actually looked at these indicators or can muster a reasoned argument about why this time is different.

I was in the Army, so I have the social cred to point out that these terms sound vaguely Orwellian and a bit stupid. “Kinetic” appeared sometime in the 1990s to distinguish shooting from “war by other means.” It seeped into military usage after 2000. As for “forced entry” as a euphemism for “invasion,” the first use I could find in a basic search of military documents was FM 100-5, Operations (14 Jun 1993), page 7-4. Before ‘93 the terms of art were “opposed landings” and “opposed assaults,” or “amphibious landings” and “air assaults.” To be fair, reason for the new term was not Orwellian; it was to come up with a term that could capture both air and sea operations; “invasion” didn’t work because it implied strategic intentions that don’t usually hold. Nonetheless, the phrase sounds like a euphemism, since “forced entries” in the civilian world mean breaking locks, not shooting people.

But maybe they’ll pick somewhere else, I don’t know, I’m a sergeant, not a strategist. Go ask the Secretary of War. I’m just telling you the minimum size of the operation and telling you what to look for if it was going to happen.

The inspector-general’s report on the mess is a gold mine. In case of link rot: “Evaluation of the DoD’s Capabilities to Effectively Carry out Joint Logistics Over-the-Shore Operations and Exercises,” Office of the Inspector General Project No. D2024-DEV0PC-0163.000 (2 May 2025).

In 2023, the Navy decommissioned its only East Coast JLOTS unit, leaving only one other unit in California. But the Army had the 7th Transportation Brigade in Virginia and the 3rd Transportation Brigade in the USAR, so all was not lost. Sadly, in an organizational SNAFU that brings up memories of my time in the 369th Corps Support Battalion, the 3rd Transportation Brigade lacked the subordinate units that would actually build the modular causeways. (Head, desk.) Luckily, now the Navy Reserve rescued the Army — the Navy Reserve had seven battalions trained to load and off-load bulk cargo. But then we ran into the problem that the Army and Navy use different docking standards. Navy docks sit higher in the water, so you have to bend things to get them to hook up, whereas Army watercraft aren’t designed to get close to Navy docks without banging them up.

Hey, that’s the Defense War Department for you.

From the link: “Salaries are a major cause of discontent. The Venezuelan military is among the lowest paid in the world, echoing the national economic calamity: at current exchange rates, a general’s wages do not exceed $10 per month, while for low-ranking soldiers they are slightly over $2.”

Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy LPD-17 Amphibious Ship Procurement: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress,” Congressional Research Service (9 June 2009).

Ah, memories of 2002 in New Jersey. Or driving between New Haven and Fort Dix every week just to make that happen.