Invading Panama, a historical guide

The country came pre-invaded the last time around

The U.S. has invaded Panama with some frequency. What they all have in common is that Panama arrived “pre-invaded”: that is, American forces were already positioned on the Isthmus. Even in 1989, the amount of men and materiel that needed to be moved in from CONUS was minimal.1

TLDR: Invading Panama would be hard, even without Panamanian resistance. But it’s doable, from a military point of view. Economically and politically, however, it seems like a bad idea.

Before Blue Spoon: A short history of interventions

The American military regularly intervened in Panama during the 19th century, when it was a province of Colombia.

By 1904, with the new country of Panama in place, the Roosevelt administration was tired of using tortured readings of preexisting treaties to justify sending force. So Secretary of State John Hay communicated to the new United States ambassador to Panama, William Buchanan, that it would be “preferable that the Panama constitution should contain nothing in conflict with the widest liberty on our part.”

Buchanan in turn urged the Conservative Party in Panama to support the inclusion of Article 136 in the Panamanian constitution of 1904. The Conservatives acceeded to the request, and we got, in the constitution, the following:

The Government of the United States of America may intervene in any part of the Republic of Panama to re-establish public peace and constitutional order in the event of their being disturbed, provided that that nation shall, by public treaty, assume or have assumed the obligation of guaranteeing the independence and sovereignty of this Republic.

The U.S. started to use this authority almost immediately, but none of these interventions rose to the level of “invasion” or “occupation.” In November 1904, President Roosevelt deployed the Marine Corps to forestall an attempted military coup by a disgruntled former Colombian general. (The Marines were already in-country to dissuade Colombia from retaking its rogue province.) The coup leader resigned his commission, and Panama abolished its army soon thereafter.

In 1908 and 1912, at the request of the Panamanian government, U.S. Army soldiers and civilian Canal Zone officials supervised registration and voting in Panama, while the USMC stood ready to intervene should violence break out. In April 1915 a riot broke out over a baseball game between a bunch of American soldiers and the Cristobál team. (The Americans lost, beginning a long tradition of Panamanian baseball excellence.) The riots grew of control and a Panamanian police officer (probably!) shot and killed an American soldier. The local U.S. commander briefly sent active duty soldiers out on patrol, although it is not clear that they actively did anything to restore order. When the U.S. chose to not supervise the 1916 election it prompted widespread protests by Panamanian opposition politicians.

In 1918, acting-President Ciro Urriola unilaterally declared that he was postponing the midterm elections. The U.S. was in contact with the opposition, and the Secretary of State himself announced that the action was not acceptable. Once again, the Army swung into operation—I can’t really call it “action”—disarmed the National Police in Colón and Panama City, and supervised the elections.

In Chiriquí Province, however, the situation collapsed into chaos. The American sent to supervise elections wound up staying and creating an occupation government. This was tied up in a bizarre—and I mean bizarre for the time—attempt by the Panamanian government to convince the Americans to subsidize Puerto Rican settlement in Panama’s border regions with Costa Rica. Needless to say, that didn’t happen.

Historians disagree on the motives behind the decision to take a Panamanian border province (and location of the second-largest city, David) and try to create an occupation government. Some of it may have to do with Panamanian pressure to get Puerto Rican settlers. Another bit was that several Americans had purchased cattle ranches in the province and violent cattle rustling was on the upswing. Rustlers had killed at least two American citizens and the Panamanian police appeared incapable of handling the situation.

It gets weirder. A Jewish-American corporal (or maybe sergeant? sources vary) from New York, Abraham Solomon, winds up personally damaging Panamanian-American relations. The Assistant Department Intelligence Officer of the Panama Canal Department, U.S. Army, writes the following about Solomon:

There was an enlisted man in the detachment, Sergeant Abraham Solomon by name, who was so influential in Chiriqui affairs that he was familiarly called “the Mayor of David.” He personally captured most of the cattle thieves apprehended, and turned them over to the Policia Nacionále [sic] for Captain Grimaldo to take the credit.

In June 1919 the actual mayor of David writes the national government complaining, “there is a soldier named Salomón who ... interferes in everything, and the information that he gives to his superiors is generally false and based on rumors.” Solomon goes on to threaten county officials across the province and eventually winds up crossing the border into Costa Rica in hot pursuit of Cruz Jiménez, a suspect in the murder of an American resident. Solomon shoots Jiménez dead. He then separates from the Army in 1920, only to have the Panamanian Attorney-General write the President, saying that they need to get him for the secret police, “with the object of having him on our side, or, at least, of neutralizing him.”

Solomon instead goes to work with an American rancher, William Chase. Later winds up the subject of an international investigation into his decision to capture and detain a trespasser for a day. Solomon gets arrested, charged, acquitted, and then he decides to sue the Panamanian government for wrongful detention. He wins and goes home with a $5,000 indemnity from the Panamanian government. That’s $88,158 in 2024 money—probably less than Solomon expected to make, but not bad.

That’s some serious chutzpah.

What happened to that guy? Surely he went to work for Meyer Lansky, got rich, and died of a heart attack after a seder surrounded by grandchildren at his home in Rosslyn, Long Island, in 1962. Either that or he had a long career as an NYPD detective and also died after a seder, only this time in Marine Park, Brooklyn, instead of Rosslyn. Or so I want to believe.

Anyway, I digress. The occupation is a mess, as the Solomon story makes pretty clear, and the U.S. pulls the troops out of Chiriquí in 1920.2 Unfortunately, two gunboats and a battalion of Marines has to return the next year after Panama sends an armed expedition to expel Costa Rican forces from the contested town of Coto. You can see Coto on the left edge of the above map, where it reads, “Teatro de la guerra entre Panamá y Costa Rica.”

Finally, in 1925, the Panamanian president calls in the U.S. Army to restore order after local firemen fail to break up a Panama City rent riot by turning their hoses on the crowd. Six hundred American soldiers move into Panama City with fixed bayonets to quell the riots.

In other words, American forces were often on the ground. Over and over again. But you really couldn’t call any of these actions an invasion; the occupation of Chiriquí in 1918 comes the closest.

1989 and all that

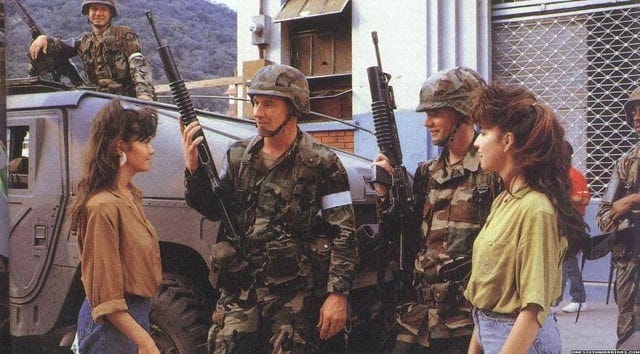

So things are quiet from 74 years, until Cara de Piña—also known as Manuel Noriega—starts going out of his way to antagonize the United States. This all comes to a head on May 5, 1989, when Noriega steals the presidential election for his chosen candidate. Noriega not really thinking things through, does this in the heyday of modern opinion polling, with polls showing opposition candidate Guillermo Endara ahead by 40 points. When Endara organizes a protest, Noriega’s goons beat Endara unconscious—this was not easy, Endara weighed about 250 pounds—and then they sprayed the crowds with water cannons from trucks painted with pictures of the Smurfs on the side.

At that point, on July 26th, our boy Noriega announces that Panamanian representatives will boycott meetings of the Panama Canal Commission. The incoming Bush administration publicly announces that it won’t accept anyone nominated by Noriega to head the Commission. Privately, this is the last straw, and the famously prudent George H.W. Bush decides that it’s time to prepare Operation Blue Spoon (I guess to scoop out the Smurfs?) and wait for what he calls a “trigger event.”

That happens on December 15th, when Cara de Piña follows in the footsteps of … uh … Adolf Hitler? He declares war on the United States. And I’m not meaning cheap talk. He formally gets the National Assemby to declare war on the United States.

Panamanian Defense Force members start attacking American troops and their dependents, killing one, wounding three, and sexually assaulting a fifth. On December 17th, President Bush makes his decision, with the immortal words: “Okay, let’s do it. The hell with it!” His political advisors change the name of Operation Blue Spoon to Operation Just Cause—setting an awful precedent—and the invasion starts at 45 minutes past midnight on December 20th, 1989.

The Panamanian Defense Forces were not a particularly serious opponent. They consisted of a sum total of 3,500 actual soldiers. (The other 11,500 were poorly-trained policemen.) Its equipment, in addition to the Smurf trucks, consisted of 29 armored personnel carriers and 28 light aircraft. These guys were great at neutralizing domestic opposition, running drugs, and setting off bombs in Sandinista government offices two countries over. Actual fighting? Not so much.

Conversely, the United States had 12,000 troops within the country even before the Bush administration started its surreptitious buildup after July 26th. The U.S. also had “Elaborate Maze,” a beautifully-named series of contingency plans from the era before the we started giving military operations stupid propagandistic titles like “Just Cause” or “Desert Storm” or “Enduring Freedom.”3

In the early preparation for the invasion, President Bush ordered 1900 troops to Panama as part of Operation Nimrod Dancer (seriously, these names were art) in an effort to protect U.S. citizens. It required 55 flights over 24 hours from bases in California, North Carolina, and Louisiana. The transport flights landed at U.S.-controlled military airstrips in the former Canal Zone. Nimrod Dancer patrols started scouting outside American bases and posts.

And what did Noriega do? He ordered his forces to let Nimrod Dancer patrols do whatever the hell they wanted to do. He won’t interfere with them until December.

In August, General Colin Powell reworked Operation Blue Spoon to speed up the final deployment of 27,000 additional soldiers from three weeks to five days. Note: five uncontested days. This was a plan for a buildup to start a forced entry operation from inside Panamanian territory, not a plan for a invasion from CONUS.

On December 19, we started the airlift. 200 aircraft participated in the deployment. Note again that this was a deployment from the CONUS to U.S. bases in Panama. No shooting.

And so, D-Day involved 20,000 U.S. forces going up by land against 3,500 Panamanian soldiers who had no air support and no air defenses.

Immediately after D-Day, we implemented Operation Blind Logic, which the Bush Administration unforgiveably renamed “Promote Liberty.” That involved sending the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion from North Carolina to help restore order, reconstitute the Panamanian police, and support the elected Endara government. There was scattered fighting, but no organized resistance. Some PDF elements fired 70 rounds at the car of U.S. chief of mission; he survived unscathed. The fighting was over by Christmas.

The U.S. then shelled out $25 for a hand grenade, $100 for a pistol, $125 for a rifle, $150 for an automatic rifle, and $150 for a mine. This worked, because nobody liked Noriega and Panamanians saw the U.S. presence as legitimate. There was rioting, but nothing like we would later see in Iraq in 2003. In other words, Operation Blind Logic was a success. The U.S. Army handed the keys over to President Endara and that was the end of that. Mission accomplished.

Needless to say, an attempt to invade Panama and secure the Panama Canal would look very different in 2025. It isn’t that Panama has more organized resistance: it probably has less.

But whatever might happen, it won’t look anything like the interventions of the 1920s or the one in 1989.

But maybe we have another model?

Operation Power Pack

Operation Power Pack was the military’s name for the 1965 invasion of the Dominican Republic. I firmly believe that most Americans would remember this today were it not for, well, the other war that started that same year. Unlike that other war, Operation Power Pack was over quickly and was most definitively a victory.

At the time, the D.R. had fallen into civil war, with the D.R. Army split into U.S.-favored “Loyalists” and U.S.-opposed “Constitutionalists.”4 Washington believed that the Communists were ready to take advantage of the split. So LBJ pulled the trigger. Now, remember that the D.R. is rather closer to the United States than Panama. In addition, technology has changed significantly. So this isn’t exactly how an attempt to secure a hostile Latin American capital would go down today. But it’s not that far away from it, either.

First, on April 27th, 1965, six Navy vessels evacuated 1,176 civilians via helicopter under fire from Dominican rebels. The next day the USMC airlifted another 1,000 civilians to ships from a makeshift LZ in the Polo Grounds next to the Embajador Hotel. This operation was cinematic and it’s kind of a shame that nobody’s made the movie.

The invasion proper started two hours after midnight on April 30th. Two paratrooper battalions from the 82nd Airborne landed unopposed at San Isidro Airfield, eight miles outside Santo Domingo. This was not that different from the Russian concept in 2022, where they sent special forces to seize airfields in order to bring in more troops later. The difference was that the Americans succeeded, given that the Dominican Army had split in two and was busy fighting itself. So the Constitutionalists in ‘65 were in no position to hit the Americans hard before they could resist, the way the Ukrainian Army crashed the Russians’ party in ‘22.

Through May 14th, a bit over 100 flights a day delivered 14,600 soldiers and 30 million pounds of equipment.

The U.S. did not, however, wait in San Isidro during the build up. (This would be very different from the way we ran Blue Spoon, 24 years later, where we did indeed sit and wait during the build-up.) At dawn on April 30th, only a few hours after landing at San Isidro, the 1st Battalion, 508th Infantry, advanced west toward Santo Domingo and secured the Duarte Bridge, blocking what was then the only route out of the city to the east. The original plan had been for the 1st Battalion to paradrop into the city, but it turned out that would have been a terrible idea, since the landing zone was covered by sharp corals. The Army pushed west across the bridge while the Marines expanded their footprint from the Embajador Hotel.

At that point, the Americans arranged a cease-fire between the Loyalists and Constitutionalists, brokered at the San Isidro airbase. It didn’t hold.

But nonetheless things sat there until May 2nd, when the Americans decided that the ceasefire was too weak to let the Marines stay in their compound with no lines of communication to the Army troops at the river. In a sign of how remarkably top-heavy the U.S. military was in 1965 the decision to move out and link up went all the way up the chain of command to President Lyndon Baines Johnson (page 93).

You might think that was great (diplomacy and civilian control!) or you might think that was terrible (micromanagement and political interference!). But it’s not how the U.S. military typically handled things in the 2000s, or, as far as I know, today.

Whatever your opinion, President Johnson gave the go-ahead to establish a corridor between the Army and the Marines around 8:45 EST. The 82nd Airborne advanced along San Juan Bosco Street, with battlions “leapfrogging” every block. That is, one would advance a block, secure it (basically from snipers), and then the rearmost battalion would advance to the front and take the next block.

The Marines did the same thing but with, uh, platoons instead of battalions.5

When the two forces linked up, an ill-timed shot by a Constitutionalist sniper caused the Marines to open fire on the Army. Fortunately, it seems nobody was hit—it was night, in 1965, so no fancy see-in-the-dark stuff—and General Robert York (U.S. Army) managed to get the Marines to stop by the standard tactic of standing up and angrily hollering at them (page 90-91).

The corridor was established by the end of the day.

At this point, the military portion of Operation Power Pack was basically over. The Americans had geographically isolated the Constitutionalist forces and cut off their supply lines. They’d kept the Loyalists under control. They’d occupied the heart of the capital city. In June, the Constitutionalists initiated a round of fighting by trying to assault American positions, but they failed. The Americans—along with 1,600 soldiers from various Latin American countries—oversaw elections. The Americans also cleverly bundled the military leaders of both factions into unofficial exile after a Loyalist general, Elías Wessin, tried to foment a coup:

Following the attempted coup, General Wessin y Wessin was removed from the Dominican Army, named the Dominican Counsel General to the United States, and forcibly placed aboard a plane to Miami by two armed U.S. officers. At approximately the same time, the Constitutionalist military leader, Colonel Francisco Caamano was named the Dominican Military Attaché to England and flown to London.

And that was that.

Panama in 2025 isn’t the D.R. in 1965, but it rhymes

There would be a bunch of differences if we tried to reoccupy the Canal today. The positive one is that Panama doesn’t have a military and armed resistance would be much lower. But then on the other side there is:

Surprise. It’s not clear that the U.S. could launch a surprise landing the way we did 1965.

Distance. Panama is further from Florida and Puerto Rico than the Dominican Republic.

Area. We would need to secure the entire area along the Canal (or at least most of it) which is rather larger than the limited section of Santo Domingo that we targeted in 1965.

Damage to the Panama Canal. If I were an American planner, I would not be worried about collateral damage. I would be worried about giving the Panamanians the chance to damage the Canal if we lose element (1), above. Now, destroying the Canal is beyond the Panamanians’ capacity. Even taking out the Gatún Dam or demolishing one set of locks would require a lot of planning and preparation. Do the Panamanians even have 5 tons of high explosive lying around to detonate in one of the locks? But sabotage—and possibly very serious sabotage, with enough notice (and quiet Chinese help)—is something the U.S. would need to worry about.

Hostile civilians. The problem isn’t that civilians would fight the occupying forces. It’s that they might engage in nonviolent resistance, presenting the Americans with some very unpalatable choices. Domestic support could unravel very quickly. (More on this below.)

New technology. I don’t expect, say, civilian drones to overwhelm our occupation forces or anything like that. But I do think that they will complicate the operation, particular since the military will be operating under conditions of almost complete transparency. This is a huge difference from 1921 or 1965 or 1989 and it is too often underrated.

We would need to occupy several airfields at once, seize the Gatún and Miraflores locks, and then secure the banks of the Canal. It’s not undoable. But it would be messy and require a lot of manpower. The problem, essentially, is that there are now civilian settlements up to the banks and anyone can walk right up:

It’s not that somebody standing where I stood could damage the Canal. But they could make life miserable for the occupying soldiers unless they were willing to act quite brutally, which would generate costs domestic. I know many MAGA types, they are my friends and relatives. Heck, I am close friends with people who’s political opinions I consider completely insane. And most of them would blanche at shooting Panamanian civilians in Panama.

That dilemma wouldn’t go away, since we would need to keep it secured against interference. I am fairly certain that the PRC government would do everything in its power to foment interference, up to (and perhaps beyond) the point of plausible deniability. Eventually we would need to build a wall. The occupation and defense costs would eat up Canal profits. So would foreign boycotts, at least for a time.6 The U.S. would either need to keep rates high or subsidize Canal operations.

And I have to reiterate that Panama is one of the most popularly pro-American countries in the hemisphere. Attacking a country where the median person-in-the-street actually kind of likes the United States seems like a very stupid thing to do.

But an invasion is not undoable. We did something sort of like it in 1965, with Operation Power Pack.

But I really can’t imagine that it would be worth it, either economically or politically.

I know that this dive has ended with the conventional liberal wisdom. But I hope you think that the ride was nonetheless worth it, because conventional wisdom often derives from emotional desires and wishful thinking, without consideration of historical examples and logistic realities.

Plus, you got to learn about Abraham Solomon, who really does seem more like a character out of a Graham Greene novel than a real actual person.

CONUS means the lower 48 states. When I was in the Army I liked to imagine that it stood for “Contiguous On North-america, United States.” It doesn’t. It’s “CONtinguous United States.” But whenever an acronym was written in all caps that wasn’t a first-letter abbreviation I felt like the authors were suddenly SHOUTING at me. CON-tiguous! Which might have been pedantry or might have left-over bad feelings from getting my first introduction to the Army at the fort formerly known as Benning.

The episode is worth further study, if somebody can dig up the details from the War Department archives. I suspect that the Army lacked orders or strategy and was just winging it, with no idea what they wanted to accomplish.

I was in the ARNG and I am well aware Army custom capitalizes the names of OPERATIONS. Army custom is stupid, I say as a third-generation “The Army does a lot of stupid things” person who joined the Army and has a son who wants to join the Army.

There is a lot more detail here, of course, and the actual morality of the question is uncertain. It is very unlikely that the D.R. was about to fall to an outright Communist revolution and become part of the Soviet Bloc. On the other hand, the country was experiencing the start of a civil war that could have become prolonged and terrible.

Yes, this makes me think I should have been a Marine. Although seriously, I should have done what I really wanted to do at age 18, and become a submariner, like Jimmy Carter. But I digress.

It would not surprise me to see foreign governments boycott the Panama Canal after an American invasion. But neither would the opposite.

![r/HistoryPorn - Camión Pitufo (lit. Smurf truck) of the Panama Defense Forces, Mercedes Benz trucks equipped with water cannons that shot chemical laced water to crowds protesting against the military government, 1987-1989 [800x473] r/HistoryPorn - Camión Pitufo (lit. Smurf truck) of the Panama Defense Forces, Mercedes Benz trucks equipped with water cannons that shot chemical laced water to crowds protesting against the military government, 1987-1989 [800x473]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!YxrX!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa39856b7-801b-46aa-a338-7c511e76f49a_800x473.jpeg)

For some reason, I can't access this in the Substack app when signed in! This is Noel, not some anonymous commentator.

So ... I dunno, Randy, maybe you're right. But it is not how I would bet. You may have noticed that President Trump is bleeding support. Given how low his starting approval was, you can be pretty sure that's not from liberals who voted for him.

Would the outspoken MAGA types on social media justify or deny casualties? Of course! But that's irrelevant. What you want to ask is whether the marginal (or even not-so-marginal) Trump voters would ignore it. And that's where I say no, no they wouldn't.

If I may, since our countries aren't that different (for all the silly claims otherwise), the Conservatives bled support once Trump started attacking your sovereignty. That doesn't mean that Conservative supporters suddenly gave up all their opinions! It means that they rallied around the forces of right ... and the forces of right were smart enough to appoint Mr. Carney as PM and dump the unpopular social stuff.

Maybe you're convinced that the same wouldn't happen in the USA if we suddenly invaded Panama and shot up a mass demonstration. But I would contend that you're making the mistake of assuming that Americans are a weird alien species, rather than your close cousins.

Best,

Noel

P.S. Remember, I'm a Dutch citizen, and my other countrymen voted for another blond guy with a bizarre haircut who WOULD HAVE WON had Nederland used the same voting system as the USA or Canada. And the Dutch are rather more distant from America than you are. If I may, your country has been playing with fire for the last decade, and its only a combination of President Trump and that fact that the Liberal Party is an essentially undemocratic institution willing to throw overboard the opinion of its activists what has saved you.

God bless the Liberal Party of Canada, may they continue to never believe in anything. Would that we had such a party here.

Is anyone else having trouble seeing the comment section on these posts?