Mauritius and British guilt

The past sticks around — even when it doesn’t have much to say

In a very perplexing decision, the United Kingdom handed Diego Garcia (and the rest of the Chagos Islands) over to the Republic of Mauritius. In return, the U.K. will pay Mauritius £101 million per year for the right to use a military base that the U.S. and U.K. already use. Tory governments set the wheels in motion after a non-binding World Court advisory opinion, but we do not know how they would have handled the final negotiations. We do know that the current Labour government handed over the territory.

I find this decision fascinating, because it makes no obvious sense! Why would Britain do that? In the next post, I’ll discuss the agreement itself and possible proximate reasons. Here, though, I want to dive into the history to see if there is a deeper reason for London’s decision. Might Britons have reasons to feel guilty about their colonial legacy apart from the Chagos?1 If so, then the decision would be entirely understandable even if the proximate reasons seem weak.

TLDR:

Guilt for taking the locals’ land and freedom? Mauritius was uninhabited before the Europeans got there, and anyway it was my people what first took it, not the British.2

Guilt for slavery? Well, yes. Britain was all in on that. But slavery would have existed on Mauritius without any British involvement. Britain had already banned the slave trade before it conquered the island from the French and abolished slavery within a quarter-century of the annexation.

Guilt for economic exploitation? Mauritius grew pretty fast under British rule and living standards were pretty high. It reached the levels of southern Europe well before World War 2. Britain protected the Mauritian sugar industry and made fairly large fiscal transfers to the island in the decades before independence.

Guilt for post-colonial instability? Many British colonies fell apart after independence, with the collapse of both democracy and the rule of law. Mauritius is not one of them.

Guilt for throwing out a people who wanted to be British? Well, yes. Britons should feel bad about that! British people, in my experience, just don’t realize how bizarre it is that they turned their slave colonies into independent countries instead of integrating them into the polity LIKE EVERYONE ELSE. (Yes, apologies, I am shouting.) The French, the Americans, the Danes, they all made their former slaves into citizens.3 Heck, so did the Dutch, save one single shameful opportunistic episode around Suriname that never should have happened — and which the Dutch felt so bad about that they offered Suriname a chance to rejoin the Netherlands in 1991.4

That said, I do have to admit that Mauritius appears to have done fine on its own. Judging from Réunion — which became part of France proper and received direct fiscal transfers, political representation, and full legal incorporation — they would probably be a bit richer. But Britain never offered anything like that to any of its sugar colonies, and Mauritius nonetheless did quite well.

And now, the above, but in much more detail.

Colonization

Mauritius is one of those places where the colonizing power (or powers, since the Netherlands, Britain, and France were all involved at various points) encountered no local population. Rather than settle their own nationals, however, the colonizing governments brought in forced laborers of one sort or another.

As with so many things, the Dutch got there first. They named the island after Maurits, Prince of Orange, the sorta-kinda head of state of the Netherlands at the time.5 The Dutch East India Company engaged in the general brutality for which it became justifiably infamous, but still couldn’t make it work. In 1658, they gave up.

In 1664 the Dutch tried again, and the second time was not the charm. The last DEIC chief factor was Adriaan Momber van der Velde.6 He faced rebellion by the enslaved, food shortages, pirate attacks, and drunken subordinates with a penchant for trying to kill each other. The Dutch withdrew in 1710 and the French claimed the island in 1715.

Slavery

The Dutch did not evacuate escaped slaves, however. The former slaves understandably resisted French encroachments and weren’t defeated until 1739. There are no clear records (that have yet been discovered) detailing what the French did with the surviving freedmen, but we do know that they recognized a free Black population: the Code Noir of 1723 — which mandated cutting the ears off a recaptured escapee — subjected free Blacks to a daily fine of 10 piastres for sheltering a fugitive whereas whites were only fined 3 piastres for the same offense.7

The French were generally unable to effectively control their enslaved subjects. Four percent of enslavees escaped every year, and that number rose to a staggering 11-13% in the two decades before the British invaded in 1810 … roughly 6,800 to 8,500 people annually.8 On the other hand, life was hard on Mauritius, and sex-ratios were skewed, so the island did not develop a large free “maroon” community the way Jamaica did.

Which is not to say that there weren’t free Mauritians of color! The first recorded property purchase by a Black person appears to have occurred in 1748. The first land grant to a Black person went in 1758 to Elizabeth Sobobie Béty, the daughter of the King of Foulepointe, a slaving center in modern-day Madagascar. (In other words, she was the daughter of an African enslaver rather than the daughter of former slaves.) By the 1770s, 15 percent of land grants went to free Black people … half of whom received them as a reward for their service in recapturing escaped slaves.9

By 1806-07, on the eve of the British invasion (the one in 1810, not 1964), free people of color consisted of 8% of the population, which owned 9% of all cultivated land and controlled 15% of the enslaved population.10

Mauritius in 1810 looked a bit like Trinidad, which the British also took over from the French Spanish (in 1797).11 And as in Trinidad, once Parliament abolished slavery, Mauritian landowners looked around for a new source of labor and found it in India.

“This Inhuman Traffic”: Indian slavery in Mauritius

But there is one difference with Trinidad, which is that Indians were already present on Mauritius. Mostly as slaves.

The first Indian slaves arrived in 1728. The French took around 5,000 people (mostly to Reunión) in 1670-1769 and about 15,000 in 1769-1810, at which point there were 6,162 slaves of Indian descent on Mauritius.12 We don’t know much about how Indians became enslaved, other than from the aforementioned report from the EIC head: “It has long been the custom of the Moplas [Muslims] to steal the children of the Nairs and other Gentoo [Hindu] castes and carry them to the coast for sale.”13

We know that there was also significant free migration from India to Mauritius, enough that the French colonial government put the kibosh on it, but exact numbers have not yet been uncovered.

In May 1792, W.G. Farmer, the East India Company’s (EIC) officer-in-charge at Calicut on India’s Malabar Coast (now Kerala state), wrote an extensive report about the “evil” French slave trade from India. I don’t mean “evil” as a scare quote; I mean “evil” as in Mr. Farmer called it evil, which it certainly was, going on to discuss in great detail “the very extensive slave trade carried on by the French at Mahé from whence numerous cargoes have of late been carried for the supply of the islands of Bourbon [now Reunión] and Mauritius.”14

The East India Company decided that the French trade was going to harm Indian stability, being against “every regulation which could be framed for the improvement of the country, and for the happiness and welfare of the people.” The board ordered its agents to wipe out “this inhuman traffic.”15

That was a little disingenuous, considering how the EIC had been in up to its eyeballs in trading enslaved Indians over the previous century.16 And the EIC’s sudden turn to abolition had a lot to do with its battle with the Sultan of Mysore, the leader of a Muslim kingdom backed by the French. But I’m an American, so I’m fine with doing the right thing for the wrong reason. And being late generally beats not showing up at all.

Come the British

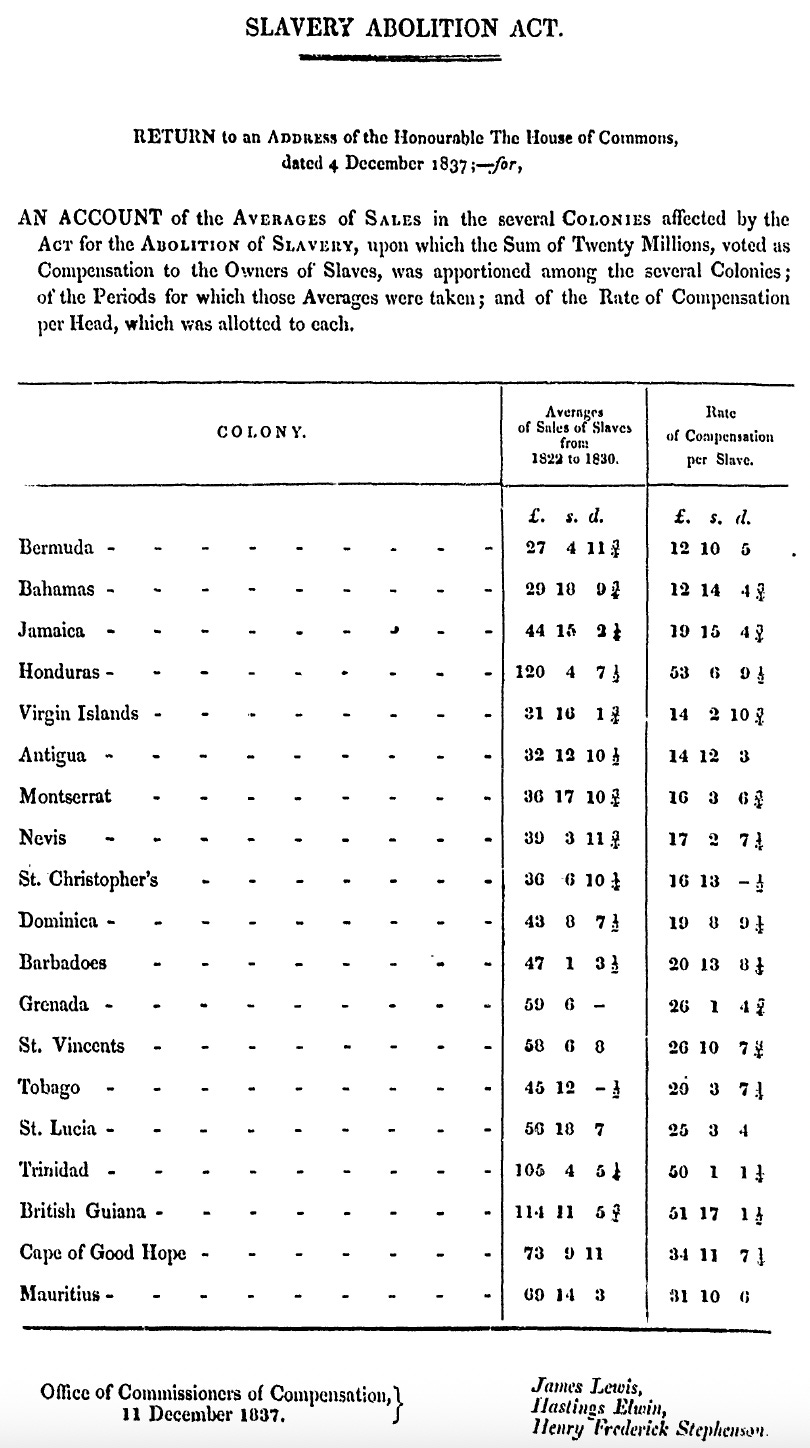

The British conquered Mauritius in 1810, during the Napoleonic Wars, and abolished slavery in 1834. They collected 74,000 sales observations across their possessions to determine compensation. In Mauritius, slave prices averaged almost £70. This was almost 50% higher than values in Barbados or Jamaica:

While the data is spotty, some circa-1770 records indicate that slave prices hovered around £26 … the implication being that prices on Mauritius were rising, not falling as in the West Indies.17 Despite high mortality and extraordinarily high escape rates, Mauritian slavery was quite lucrative for the slaveowners.

The British abolished slavery anyway, twelve years before France did so in 1848. Of course, we have to point out that this was an easy decision, since nobody in Britain had any economic interest in Mauritian slavery. The slave and plantation-owners were overwhelmingly local residents of French or African descent.

The British government refused to give “full” compensation to the enslavers: each one received less than half the market value. But that’s also not really an example of British virtue. Had all slaveowners been forced to sell at once, then the sales would have fetched much much less than £70 per person. Parliament knew that and so fixed compensation at a lower number. Either way, the slaveowners received quite a tidy sum: in today’s money that’s £3,806 for each captive … or, for our American readers, $5,268.

So how poor was it?

OK, so Mauritius looked a lot like nearby Réunion, including the fact that a lot of the enslaved lost their freedom in southern India or Bengal instead of Africa. And in both places large numbers of Indian indentured and unencumbered laborers immigrated in the decades after the end of slavery. Why one became an integral part of the Republic while the other became independent is just one of those mysteries of the English, along with their quaint oral traditions and powerful spirit of neighborly cohesion and amusing drinking customs.

But, well, how bad off was Mauritius? Was it poor? Did it become richer? Can we find circumstantial evidence that the British exploited or mismanaged the place?

The nominal wages paid to an indentured laborer on Mauritius in the early 1840s were about 70% of the nominal wages earned by an agricultural laborer in England. The gap for skilled laborers was greater — they earned a bit more than 40% of an English “artisan,” but the mix of skills was likely different so it’s not a great comparison.18 Your English worker, however, had to pay a lot for heat … but also lived in a more salubrious disease environment and certainly paid a lot less for clothes and manufactured goods. On the other other hand, the Mauritian staple diet was cheaper on a per calorie basis. In other words, it’s hard to say anything concrete about comparative living standards before 1860 without a lot more research than I am going to do for a Substack post.

But we know a little more about the second half of the 19th century. Work by economic historians supports the hypothesis that living standards on the island were neither low nor stagnant. In 2021, Tom Westland at Wageningen University used grain wages, urbanization rates, and commodity trade data to estimate the GDP per capita for various countries in 1900. Mauritius clocked in at 40% of the U.K., above Finland or Greece or Portugal and around the same level as Italy.19

The Mauritian economy wasn’t stagnant during British rule, either. In 2018, using a different methodology, Luke McLeary (Barcelona) calculated that growth in real GDP per person accelerated after 1860 to a rapid (for the time) annual rate of 2% all the way through 1938.20

These broader estimates jibe with what we know from micro-level data on wages and the cost of living. In 2012, Ewout Frankema and Marlous van Waijenburg calculated real wages for Mauritius. They found that real wages for urban unskilled workers on the island grew at 1% annually in the 1880s before accelerating to 2% in 1890-1920 and then accelerating further to 3% in 1920-50.21 Mauritius was not rich by the time the 1963 general election put independence on the front-burner, but it had reached at least southern European levels of prosperity, as this graph of GDP per capita indicates:

Whether this is a good performance or a bad one depends on your standards:

Good: Mauritius grew much faster than most of the world. World GDP per capita slightly more than doubled in 1870-1940. South Asian and West Indian incomes grew far less: about 50% and 80% respectively. Mauritius, however, grew fourfold. Rising to Southern European levels was quite an accomplishment.

Bad: Mauritius continued to get richer after 1900, but it stopped catching up to the U.K., stagnating at roughly 40% of the British level. The island’s economic performance was particularly bad over the last five years of colonial rule.

Nonetheless, Mauritius’s poor economic performance in 1963-68 was not for lack of British efforts. Britain directly and indirectly subsidized Mauritian sugar production. Moreover, starting in the 1930s, fiscal transfers began flowing to the island. The below figure shows net official transfers between the U.K. and Mauritius, excluding loans and loan repayments, measured as a share of Mauritian GDP:

Transfers averaged around 1.4% of Mauritian GDP per year between 1945 and 1968. The numbers are not exorbitant by contemporary standards: Ireland, for example, received E.U. transfers worth 4% of its GDP after accession in 1973, peaking a bit above 6% in 1991. (At the high end Alabama today receives about 16% in net transfers from the federal government; Scotland gets 10% from the U.K.) But neither are they small. Moreover, Britain gave Mauritian sugar a protected market after 1932.

For comparison, I’ve added the value of the annuity that the U.K. just agreed to give Mauritius to continue its use of the Diego Garcia bases — it comes to about two-thirds the level of postwar transfers before independence.

Independence

OK. Britain may have been knee-deep in abetting slavery, but it would have existed on Mauritius regardless until 1810, by which point trafficking in slaves between British colonies had been banned. Britain may also have undemocratically exercised sovereignty, but the alternative was continued colonial rule by France, not independence. Unlike many other colonies the island’s subsequent economic performance was quite good and living standards reached southern European levels. Finally, Britain transferred respectable amounts of aid during the late colonial period, especially when sugar crops failed or prices were low; growth only began to falter in 1963, two years before the independence conference and only five years before the Union Jack came down.

Having ruled out slavery, economic exploitation, and imperial neglect, perhaps there is still a case to be made that Britain overstayed its welcome. Perhaps the British stayed past their sell-by date? Could they have left earlier or more gracefully?

The problem with that suggestion is that the Mauritian Labour Party (MLP) did not wrest independence from a reluctant Britain. By the mid-1960s the British government had already committed itself to decolonization, and the Mauritian political leadership — whatever internal conflicts it faced — was pushing on an open door. The British agreed to grant independence during the fourth constitutional conference in London in September 1965, without significant protest or hesitation, aside from detaching the Chagos Archipelago in order to ensure continued American access to the Diego Garcia air base.

Although the Mauritian opposition floated the idea of continued association with Britain as a campaign issue, government officials in Westminster dismissed the suggestion. One MP bluntly referred to association as merely “a fighting plank for the Opposition party” and warned that the only real alternative to independence would have been “a fruitless federation with any neighbouring territory.”22

In fact, the proponents of independence would have preferred full integration into the United Kingdom, a la Réunion. The leader of the MLP, Seewoosagur Ramgoolam, only abandoned the idea in 1961 after Malta failed to get London to agree to integrate it into the U.K.23 Don’t believe the “confidential memo” cited at the link? OK, well, by 1967, the year before independence, Ramgoolam had become Premier of the country, and he restated in front of the legislature that he preferred that Mauritius would become part of the United Kingdom but for the fact that:

We are told there is not the slightest chance of this country being integrated with Great Britain ... Great Britain has no time for us. It is painful for me to stand in this House and say so, because I am a loyal citizen of the British Empire. I owe my fidelity and loyalty to this great Empire, even if it has not discharged its duties towards the common people of this country.24

As always, however, the actual story is shot through with enough irony to cure a bad case of anemia. Remember, Britain wanted to hold on to the Chagos for the air and naval bases. London also knew that popular support for independence in Mauritius was dicey. So during the 1965 negotiations the British vaguely implied that if the Mauritian Labour Party (MLP) objected too strenuously to the detachment, then London might accede to opposition demands for a referendum on continued “association” with the United Kingdom.

That may sound like a threat, but it’s not clear how seriously it was meant or how serious it would have been if carried out. All the evidence suggests that the MLP knew the British were bluffing. A Prime Ministerial briefing note directly warns against the appearance of “trading independence for detachment of the islands.”25 A history of Mauritius cited favorably on page 423 of the Mauritian legal brief in favor of their Chagos claim, bluntly concludes that the referendum ploy was likely just a negotiating device to get MLP acquiescence.26

And let’s be clear: the threat was a threat to hold a referendum, not a threat to deny independence.

It’s also worth noting that “association” meant something much weaker in British usage than it might imply to readers familiar with Puerto Rico or Réunion.27 When the British said “association,” they meant something closer to the 1967 West Indies Associated States model: domestic autonomy, which placed defense and foreign affairs in London’s hands but granted no automatic right to work in Britain and no compensating access to British public goods. Michael Corleone offered more generous terms.

And so, for £3 million, the MLP agreed to let the Chagos revert to Britain.28

Post-independence

Dutch people have two reasons to feel guilty about Suriname. First, they foisted independence on a population that clearly did not want it. Second, democratic institutions collapsed almost immediately afterwards, catapulting the new country into dictatorship and civil war.

Needless to say, that did not happen in Mauritius, despite severe ethnic tensions in the run-up to independence. Democratic institutions have functioned quite well until recently. This graph presents the “liberal democracy index” from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project. It shows the expansion of democratic institutions in Mauritius in the decades before decolonization and their postcolonial functioning quite well until quite recently:

We should note that the V-Dem scholars do not expect Mauritius’s decline to be permanent. In their words (pages 26 and 43 at this link):

In Mauritius, government media censorship efforts have been increasing significantly since 2019. In 2021, the government introduced several new regulations restricting the work of broadcasting companies and journalists. Wiretapping scandals were also among the series of actions undermining democracy. One of the longest-standing democracies in Africa dating back to its independence in 1968, Mauritius descended to a “grey zone” electoral autocracy in 2022. Yet, in a radical turn of events, the 2024 general elections led to a landslide victory for the opposition gaining 60 out of 62 legislative seats while the former ruling party was eradicated in the parliament.

The landslide victory of the alliance of opposition parties – the Alliance for Change headed by Navin Ramgoolam – secured 61% of the votes in Mauritius. It is one of the most remarkable outcomes of the 2024 election cycle. The autocratization of Mauritius started in 2019, when the Militant Socialist Movement (MSM) won an absolute majority of seats. Five years later, the MSM did not make it into the Mauritian parliament. Electoral irregularities dropped substantially, elections in 2024 were freer and fairer, and the country improved strongly in the quality of electoral registry.

Finis

I have no idea whether Britons should feel guilty about Mauritius. The British abolished slavery within a quarter-century of taking the islands from France. The country did well economically. Independence was basically uncontested. British-inherited institutions have worked fine in the decades since.

If I were British, I would feel more than a little embarrassed by my country’s refusal to integrate a recently-settled English-speaking island that clearly wanted to be part of the United Kingdom — even if the settlers weren’t originally from Britain. But I’m not sure that embarrassment would slide over into shame, let alone guilt.29

As for the separation of the Chagos, well, sure, London did carve it off. But the “threat” to insist on a referendum does not appear to have been serious and all evidence suggests that the Mauritians knew that. There may be precedents against dividing colonial territories without a local referendum, but I don’t see how that rises to the level of moral principle.

In short, I still don’t understand. But maybe there are some practical reasons for the U.K. in 2025 to accede to a World Court advisory opinion that don’t involve historical guilt? We’ll take a look at that next.

P.S. Now I have to go to Mauritius, in order to avoid violating my own preference against writing about places that I have never seen in person.

Well, the actual reason is that this post serves as a useful repository for everything I’ve learned about the slave trade from India, as comparative background for a project on slavery in colonial Latin America, in conjunction with Leticia Abad and José-Antonio Espín.

“My people” in this case the Dutch. As far as my other three peoples are concerned, I don’t think any Jews or Spanish people (let alone Spanish people from Puerto Rico) were involved and us Americans did not yet exist.

To be fair, I am oversimplifying. The French (1794–1802 and 1848) had a complex trajectory and Napoleon insanely tried to reimpose slavery in Haiti, thus leading directly to Haitian independence. The U.S. made its former slaves into citizens under military force after a civil war and took a century to make good on the promise of citizenship. The Danish West Indies were sold to the U.S. in 1917 and its residents became U.S. citizens in 1932.

I love this headline about the Dutch proposal for a do-over on the front page of NRC, February 23rd, 1991: “Commonwealth plan sows confusion in Suriname.”

The story around Surinamese independence and the subsequent Commonwealth proposal is quite astonishing. If there’s interest, I’ll tell it!

Maurits is Maurice in English, but the Dutch name makes it much more obvious how that became “Mauritius.” In Latin, Mauritius means “belonging to Maurits.” In Dutch, you pronounce the “tius” ending “tzee-us,” not “shuss.” Mau-REE-tzee-us, not Mau-RISH-us.

The “Republic of the Seven United Netherlands” is the official name of what most people call the Dutch Republic, which confusingly possessed a de jure hereditary nobility, the most prominent house of which provided the de facto head of state most of the time. Which means that it wasn’t really much of a republic. But it did unite the Netherlands. Except of course for the part of the Netherlands that it didn’t. Huh.

Some documents call him “Momber,” so maybe Spanish naming customs were still alive in the Netherlands in 1703, when he became governor? Or maybe Momber van der Velde was a mouthful, even for them.

See Richard Allen, Slaves, Freedmen, and Indentured Laborers in Colonial Mauritius (Cambridge: 1992), p. 51.

Richard Allen is the go-to guy here. If you don’t want to read his whole book(s), read “Maroonage and its legacy in Mauritius and in the colonial plantation world,” Outre-Mers. Revue d'histoire Année 2002 336-337, pp. 131-152.

See Allen, Slaves, pp. 86-87.

Allen, Slaves, p. 96.

I wrote “French” the first time because, well, because I wasn’t thinking. But the reason I made the mistake is because I used to travel to Trinidad quite often. While formally a Spanish colony, the island was settled by French creoles and French patois was spoken more commonly than Spanish — even today, I heard people refer to white Trinidadians as “French,” even though they are not. Moreover, the British took Trinidad from Spain as part of war against France. Those facts jumbled up in my head and produced the mistake. Apologies!

Total numbers of transportees from Allen, European Slave Trading, p. 18. The number of Indian slaves on Mauritius in 1806 from page 343 of Richard Allen, “Lives of neither luxury nor misery: Indians and Free colored marginality on the Ile de France (1728-1810),” Outre-Mers: Revue d'histoire no. 292 (1991), pp. 337-358.

Quoted in Richard Allen (2022) “Exporting the Unfortunate: The European Slave Trade from India, 1500–1800,” Slavery & Abolition, 43:3, 533-552, p. 536. The slaves came from four ports: Pondicherry and Madras (now Puducherry and Chennai) in modern Tamil Nadu and Dacca and Chittagong in what is today Bangladesh.

Richard Allen, European Slave Trading in the Indian Ocean, 1500–1850 (Ohio University Press: 2014), p. 63.

Allen, European Slave Trading, p. 63.

The EIC “only” exported somewhere between 1.4 to 1.7 percent of all trafficked peoples from India during the eighteenth century and stopped in 1772. Allen, European Slave Trading, pp. 35 and 59.

The prices were around 600 livres, valued at an exchange rate of ₶23.17 per pound sterling. See Allen, European Slave Trading, Appendix D. Better records for the British period may be available in the “Assistant Commissioners’ Proceedings: Exhibits: returns of sale of slaves: Mauritius” (T 71/1556), available in the National Archives. They have not been digitized.

Given the sources, I am not going to restrict myself to one significant digit! Mauritius data from Charles Pridham, An Historical, Political and Statistical Account of Mauritius and Its Dependencies (London: 1849), p. 396. English data from Arthur Bowley, Wages in the United Kingdom in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: 1900), p. 34.

To be comparable, you have to use the Maddison Project’s 2018 estimates. A reasonable implication of these estimates is that Mauritius was poorer than northern Italy but had living standards at least twice as high as the south.

With a slowdown to around 1% between 1920 and 1940, like much of the rest of the world, but less severe than many places.

Why did real wages grow faster than GDP per capita? Simply put, the prices of what workers consumed dropped faster than nominal wages during bad times. Considering that the prices of manufactured goods and land rents fell like rocks during the Great Depression, this conclusion is reasonable.

Hansard, HC Deb 14 December 1967, vol. 756, col. 679, statement by Peter Tapsell MP (Horncastle). See also CO 1036/1253 (TNA), which contains no record of any formal London-backed plan for association.

Anand Moheeputh, “Why independence was irresistible,” L’Express (12 March 2014).

Mauritius Legislative Council Debates, 13 June 1967, cols. 791 -2.

See page 41 of the written statement by the U.K. to the International Court of Justice on the Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius.

The quote from the book is: “This British attitude, however, was probably adopted as a means for persuading Sir Seewoosagur and the MLP to agree to the transfer to Britain of the Chagos Islands.”

Or Micronesia, or Aruba, or New Caledonia … I could go on.

See page 84 of Jean Houbert, “Mauritius: Independence and Dependence,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (March 1981), pp. 75-105

Yes, I am saying that the U.K. should currently include the English-speaking West Indies, Malta, and Mauritius. The separating principle is kind of obvious.