Daddy Yankee gives Argentina more gasoline

The Trump administration bails out Argentina! But why did they need it?

And so the Trump administration finally actually comes through for an ally! The Treasury just announced that it would be lending $30 billion to the Argentine Republic to prop up the peso. The U.S. Treasury will deposit the money at the Banco Central de la República Argentina (BCRA) to make debt service payments over the next few years.

Wowza. Given that Argentina has to make about $23.5 billion in debt payments between now and the end of 2026, that’s a lot of money!

But was it necessary? Well, yes. Argentina was facing a run on the peso, which started around September 7th.

What happened on September 7th? President Milei’s Liberty party got unexpectedly creamed in the Buenos Aires provincial legislative elections. The incumbent Peronists squashed Liberty, 47% to 34%. At first glance, that doesn’t look so bad: the margin was 45% to 25% in 2023. But at second glance it’s terrible. In ‘23 there were two conservative parties in the mix which collectively got 51% of the vote. So the right lost half its vote share to smaller leftish parties.1

Since the Peronist governor of Buenos Aires — Axel “Kichi” Kiciloff — is the leading candidate for the presidential nomination in ‘27, it’s doubly bad for Milei. Triply so because the election result emboldened Congress to start overturning presidential vetoes. He can’t ignore it with the national midterm election approaching on October 26th.

That said, we still have to peel the balloon further back, because the above recap begs two questions. First, why did Milei’s party do so badly? Second, why did investors react so strongly to the result? Let’s take them in turn.

Milei agonistes

Well, we’re not really sure that President Milei has much of an inner struggle about anything, but we don’t know the man, and he certainly is engaged in an outer struggle with the Argentine economy. We’ll stick with “agonistes” for now.

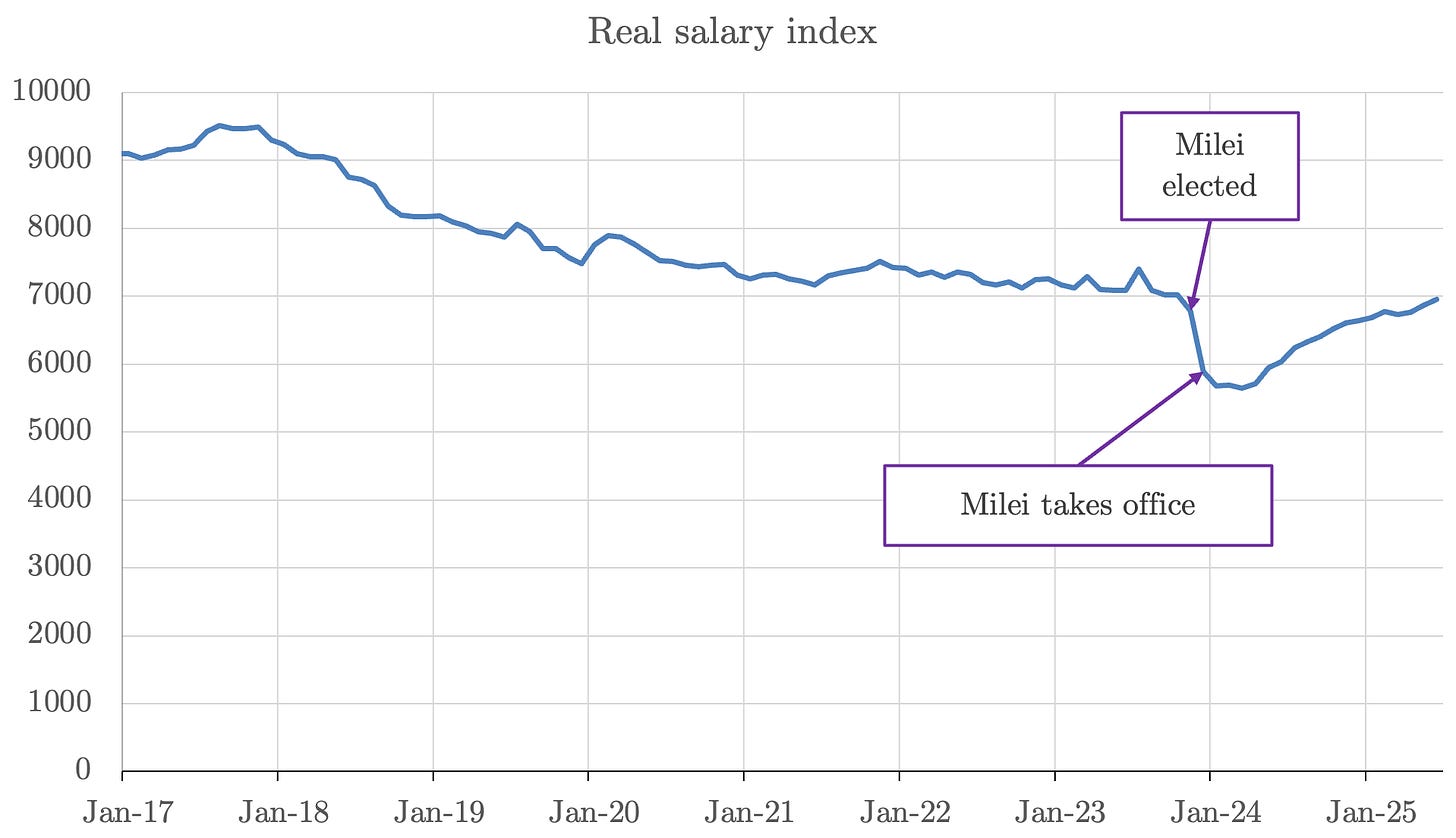

One part of the explanation for the loss is that the economic recovery has been halting. Inflation ran last month at an annualized rate of 25%. That’s better than when Milei took office, but it isn’t good by any standard. Unemployment is down slightly, but only slightly. Poverty has fallen from it’s peak, but it still around the same elevated level as it was in 2020.. Real wages have managed to touch the level they had when Milei took office in June of this year … but they are still much lower than in the recent past. And as we all know, inflation angers voters even when their real wages rise, because they view their nominal raises raised as deserved which inflation then unfairly steals away from them.2

But the economy is only one part of the wipeout at the polls, and we suspect it is actually a very small part.

The election saw an August surprise: Diego Spagnuolo, who ran the country's National Disability Agency, was caught on tape claiming that Milei’s sister, Karina, helped create a kickback scheme from pharmaceutical companies. We’ll recount what Spagnolo said because it’s juicy:

Karina is owed three or four [percent]. I calculate three because they will surely tell her that out of the five, one percent is for the operation, another one percent for me and the remaining three percent for Karina. It’s surely like that and they’re making an Olympic grab. They’re going to ask for cash from the providers. They’re embezzling the agency … behind my back. I have nothing to do with it.

I went and told him [President Milei]: “Javier, I’m denouncing all this filching and below me I have people who are going to ask for cash. What do I do?”

This is about as simple as a corruption scheme gets. Which means it lands hard. No one needs to sit down with a 20-minute explainer to understand the wrongdoing.

The President canned Spagnolo, but won’t distance himself from his sister. They have a very strange and very close relationship; he is not about to throw her under the bus. But even in the absence of direct evidence, the scandal looks terrible.

In short, there is a decent explanation of why the Libertarians lost: a corruption scandal hit amidst an incomplete recovery. But if the explanation is so decent, why did investors react so strongly to the result? Were they really that surprised?

No. They had two reasons to be scared by a bad outcome for Milei. One is economic and the other is political.

The economic catch-22 that is the Argentine peso

Milei’s anti-inflation plan has two anchors. The first is a balanced budget. The second is what’s called a crawling peg. Instead of being subject to market forces, the central bank lets the currency fluctuate inside an ever-widening band against the dollar. That takes into account the fact that Argentine inflation is higher than in the United States, but insures that the peso won’t fall in an abrupt or drastic fashion.

Empirically, most successful disinflationary programs in Latin America have involved a crawling peg.

The problem is that prices have risen by rather more than the exchange rate has fallen. We were worried about that back in October ‘24. It has since gotten worse. In other words, Argentina has become a rather expensive place to do business. To lift our explanation from October:

The “real exchange rate” tries to capture whether the exchange rate is keeping up with relative changes in inflation. For example, if inflation in Argentina is lower than in the USA, but the peso doesn’t fall at the same rate, then things will get more expensive in Argentina measured in dollars and the real exchange rate will rise. Similarly, the peso falls faster than relative prices rise, then things will get cheaper in Argentina and the real exchange rate will fall.

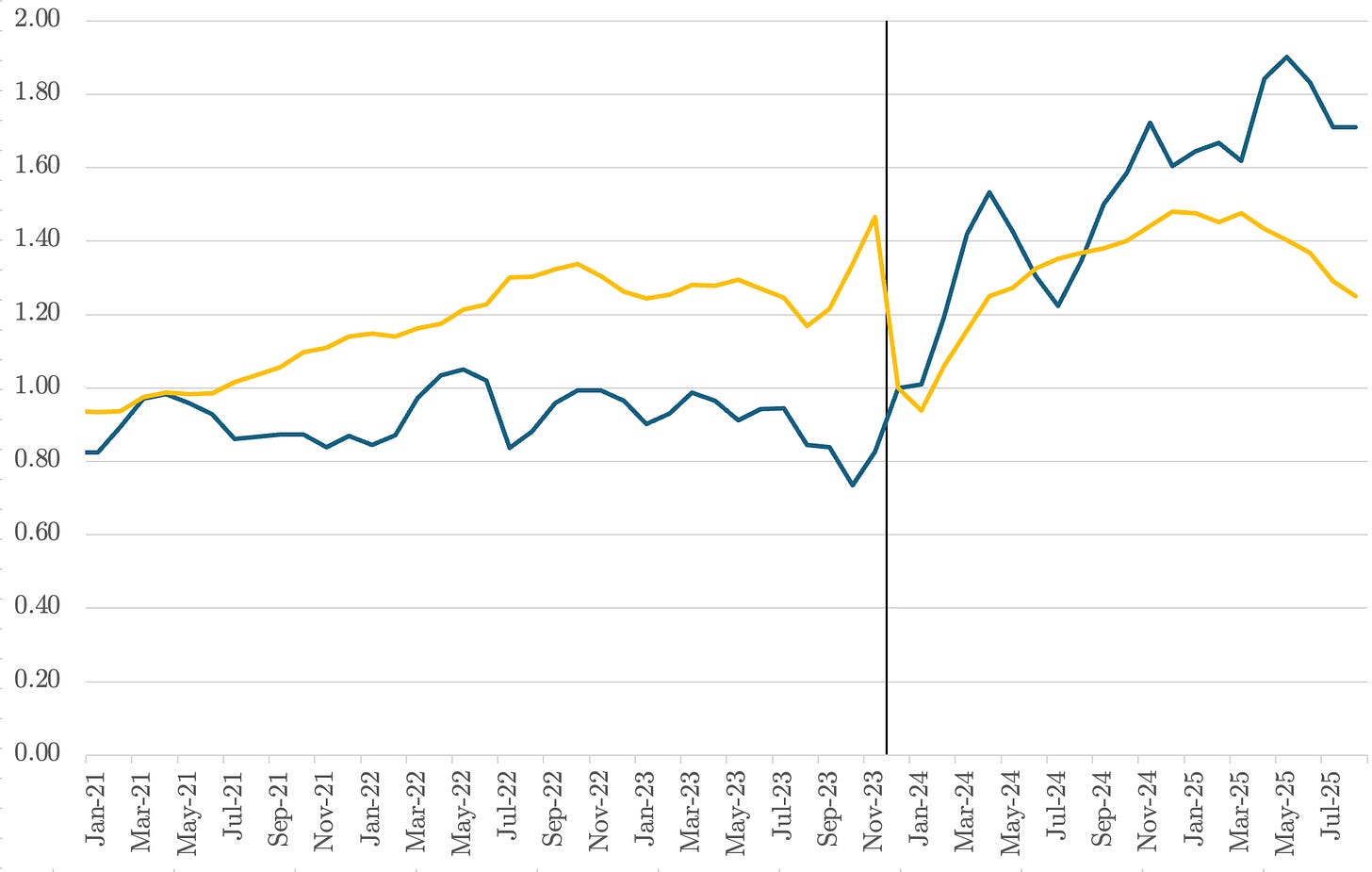

The blue line in the below graph captures the change in the real exchange rate (RER) against the U.S. dollar. President Milei took office at the vertical line. The higher the RER, the more expensive things are in Argentina relative to other countries.

As of July, the country was on average twice as expensive as it had been in November 2023. Yikes.

And that is the root of the problem. The Argentine central bank has to keep the peso within a band. That means it cannot freely buy and sell dollars. If it sells dollars, it will drive up the value of the peso … but then the central bank will use up its supply of dollars, which it needs to make debt service payments. If it buys dollars, it will build up its reserves, but the central bank pays for those dollars by printing up pesos and exchanging them in the market. It it does that, then the value of the pesos will fall against the dollar, and the effect on inflation from running the printing press is left as an exercise for the reader.

So the BCRA can’t accumulate dollars by going out on the market and buying them unless it wants to blow up the exchange rate band. Doing that, however, risks igniting inflation or crushing interest rate hikes.

If the Argentine economy were regularly selling more to the rest of the world than it was buying from it, then that would not be a problem. Dollars would flow in, and a lot of those dollars would end up in the coffers of the central bank. The analogy is with a person: when you sell more to the rest of the world than you buy from it, you’ll use some of that surplus to invest in shares or bitcoin or lend to your sister or whatever, but a lot of it will end up in your bank account, which you can then use to pay interest on your debts.

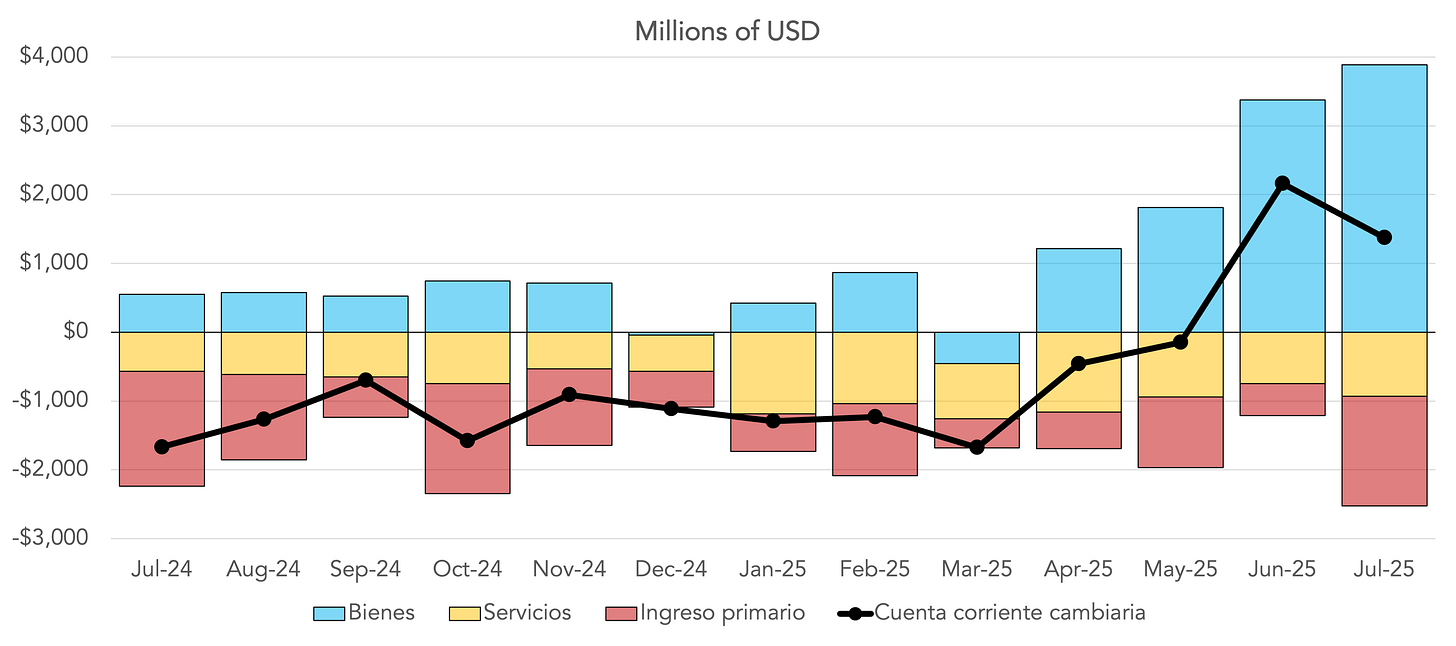

Except, well, Argentina lost its surplus at of the start of this year. In the first quarter of 2025, Argentina’s current account surplus plunged from US$176 billion in the first quarter of 2024 to negative $5.2 billion.3 The cause was not a fall in exports — in fact, exports rose by $1.2 billion.

Nope, two things killed the surplus: a $4.2 billion dollar rise in goods imports and a staggering $2.8 billion deterioration in net tourism revenues. In other words, as the peso’s real exchange rate went off exploring Mars, Argentines took advantage of cheap relative prices elsewhere to buy stuff from overseas or go vacation in Brazil. And that blew open a hole in the current account deficit. Which meant that Argentina had to either run down its holdings of foreign assets or borrow from abroad to pay for those cheap imports and bargain vacations.

But even that wouldn’t necessarily be a problem but for the fact that …

No hay plata

The Argentine central bank doesn’t have any cash.

Really, it doesn’t have any cash. If you just look at the gross headline figures, it’s sitting on almost $40 billion in foreign exchange. But most of that is tied to either bank reserve requirements (which the BCRA technically owes to the banks in dollars) or Chinese swap lines. Netting that out leaves you with only $6 billion.

Except about half of that is needed to cover three-year dollar bonds that BCRA issued to help importers pay their foreign suppliers. (The importer bought the bonds with and received a promise to get paid back in dollars at 3% interest.4) That leaves you with only $3 billion.

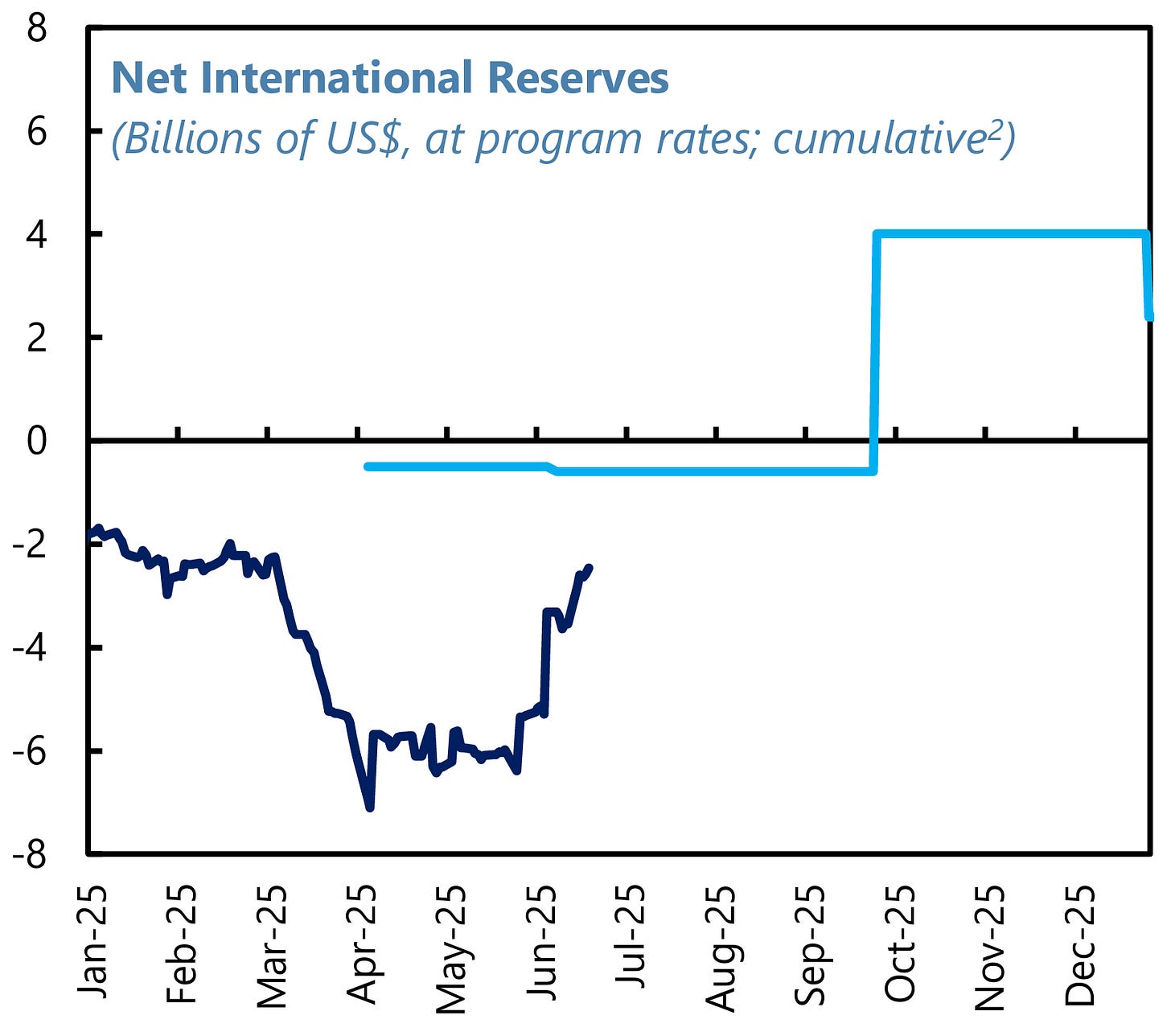

Only … the IMF thinks the situation is even worse than that. It thinks that when all is said and done, the BCRA’s liquid reserves are negative:

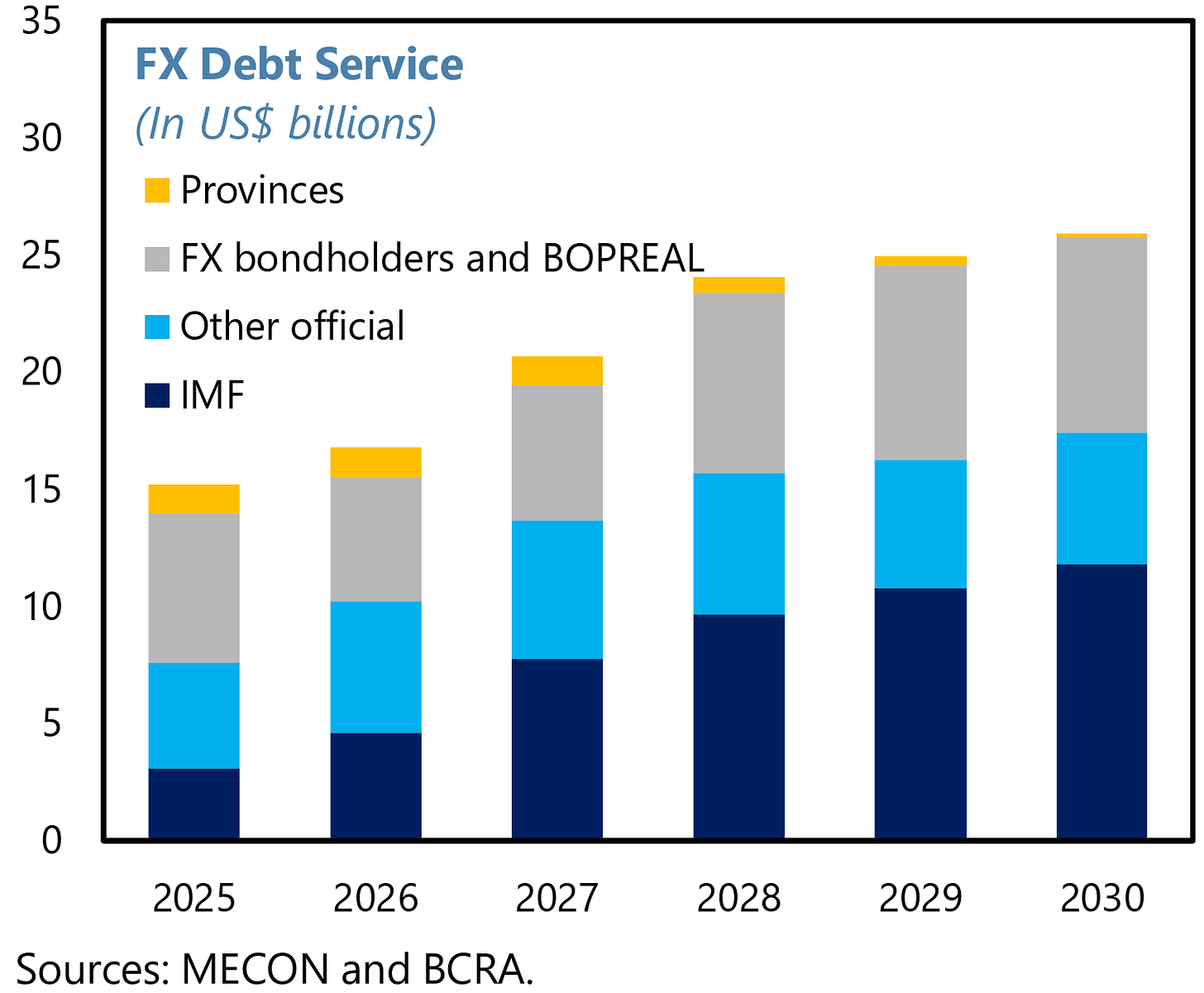

And this is a problem, because as we indicated earlier, Argentina has bills to pay: $6 billion left this year and $17 billion next year. Foreign creditors want dollars, and if Argentine businesses aren’t earning them then somebody else is gonna have to cough them up.

But Argentina doesn’t have dollars! It could get them by letting the peso fall. Exports would rise and imports would fall. So dollars would flow in. But that would smack the country in the face in three other ways:

The government collects taxes in pesos, which it then exchanges for dollars. If the peso falls, then it gets fewer dollars for the same amount of pesos. So wonderful as it would be for there to be more dollars around, Argentine taxpayers would have to shell out a bigger share of their income to buy those dollars, only to hand them back over to foreigners as debt repayments. Voters won’t like that.

If the peso falls, import prices rise. And that feeds right into inflation. Voters won’t like that either.

Sometimes it is very hard to just let a currency fall “a bit” before panic and speculation take over and move things a lot further than the authorities had expected. If the central bank announced, for example, that it was widening the band even further, then history suggests it would run a big risk of provoking the very crisis that it hoped to prevent.

In the words of Nic Saldías, speaking right before the U.S. stepped in with its $30 billion, “If they lose control of the peso, they lose the [October midterm] election.”

Losing my religion

And who would they lose that election to? Well, none other than Governor Axel Rose Kiciloff. (We really wrote “Rose” but decided it was too funny to erase.) Noel met the man back in 2012, when he had the unassuming title of Secretary of Economic Policy and Development Planning, subordinate to the Minister of Economy, and a seat on the board of the newly-nationalized YPF oil company.

They should have gotten along. They were both in their mid-forties, Jewish, professors, fathers, short (around 5’7”), and held leftish economic opinions relative to the prevailing orthodoxy at the time. They did not. The secretary clearly didn’t trust this Yankee academic in the pinstriped suit.5

Kiciloff called himself a Keynesian but it wasn’t a Keynes that either of us would recognize. Rather, he seemed more like a Marxist, in the sense that he didn’t seem to believe that the price system was a good way to allocate resources. But he eloquently and cogently defended the decision to nationalize the YPF oil company. He accused YPF’s Spanish owners of tunneling, and provided evidence consistent with that story. (A Shell executive admiringly called him “Excel” Kiciloff. He knew his numbers.) Kiciloff’s claims shaped the case study of the nationalization that Noel was there to write.

The problem is Kiciloff does not seem to have learned anything from the country’s subsequent economic travails. Watch this interview. He denies that the previous administration’s fiscal irresponsibility caused the recent inflationary blowout. He couldn’t bring himself to say that a balanced budget over the business cycle might be sensible. Nor did he admit that faking economic data was a mistake. As for current problems, he just kept repeating the equivalent of “no hay dólares,” without any plan as to how to get the dólares or make do with fewer.

Kiciloff even mangled his own analysis of the 2012 oil nationalization. It’s true that the Spanish owners were hollowing out their own enterprise instead of reinvesting. But in the interview he said that’s why the government then had to control prices and subsidize energy, when in fact the causality went the other way: controlled prices —> energy shortages —> big subsidies.

In short, he just won’t admit the presence of painful tradeoffs. Milei might well be making the wrong tradeoffs, but the guy certainly isn’t trying to avoid tradeoffs. Kiciloff might.

We understand why the prospect of President Kiciloff fills investors with fear. The Peronists really did create a disaster and he gave no reassurance that it wouldn’t happen again. And if they do get a hold on Congress on October 26th, then they have every incentive to do everything they can to wreck the economy in order to help their candidate in the 2027 presidential election.

Light at the end of the tunnel?

Without the $30 billion, Argentina really had no good options. Let the peso slide, great for exporters, bad for taxpayers. You get more dollars by in effect paying more for them. Hold the line, and you risk running out of reserves and becoming unable to make upcoming debt payments. You also further crush what’s left of Argentine manufacturing.

The Argentine economy was facing a Catch-22. But if the $30 billion from Daddy Yankee materializes, then a way out becomes very clear. Milei will have to let the peso sink more than he seems to want. But if he does that, with cash in hand, then maybe the administration can take a breather and wait for the crisis to go away on its own.

The balance of payments situation already looks to be easing. Exports spiked in June and July, more than doubling to $10.2 billion. Argentines have contined to take those cheap foreign vacations, and we would not want to work in an Argentine factory right now, but if this keeps up then the dollar shortages just might eventually solve themselves. (Although keep things in perspective: those red columns on the bottom represent largely net interest payments, and those aren’t going away.)

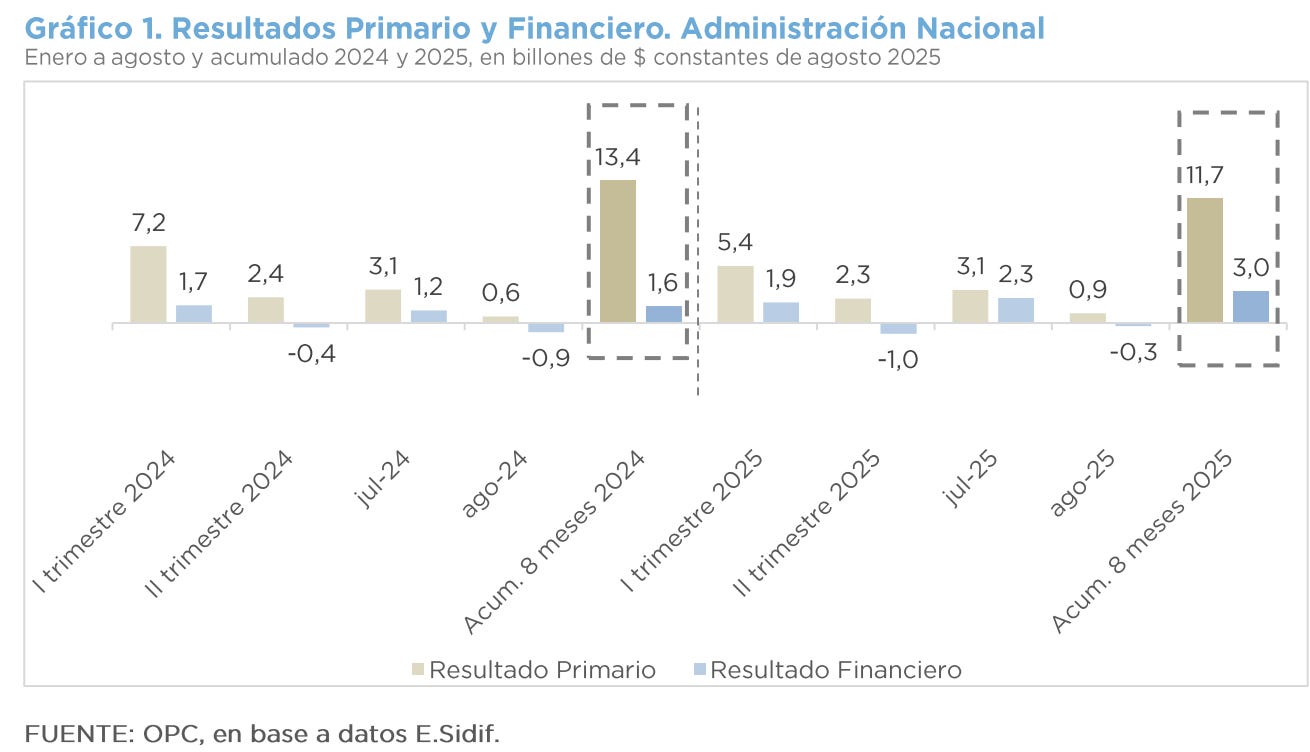

Second, despite some headlines, as far as we can tell the budget is still in generally good shape. It’s true that spending has recently moved into deficit, but that happened in the same month last year and we suspect it’s seasonal. (The relevant columns are helpfully put in dashed boxes below.) The accumulated surplus through August is still there . At some point the Milei administration is going to have to increase spending — particularly on infrastructure — but it still has breathing room.

Add a $30 billion lifeline to the above and things should — should! — work out. If Milei can make it out of the midterms without too much disaster and assuming that the commodity boom holds, then Argentina should be able to get out of the woods. The peso has to go down and inflation will temporarily go up, but them’s the breaks. That much ammunition from Uncle Sam will make a difference.

But it’s Argentina. So you never really know! Nobody’s lost money betting on an Argentine crisis.

The Peronists picked up three seats in both the lower and upper houses (gaining an outright majority in the Senate); the conservatives crashed from 54 seats (between two parties) to 30 (in one) in the lower house and from 25 to 16 in the provincial Senate. There are 92 seats in the lower house and 46 in the Senate.

Diego employs Juan as an auto mechanic. Diego thinks, “Juan is a good mechanic. He deserves a 2% raise. But inflation is running at 6%, so I better give him an 8% raise or else he might quit or become demoralized.”

Juan gets his 8% raise and thinks, “Damn, I’m good! I got an 8% raise. But these price hikes are eating up my raise. If it weren’t for this inflation, then I’d be a lot richer! Damn you, Biden.”

We’re comparing the first quarter of 2025 with the first quarter of 2024 in order to account for seasonal effects, but the story is about the same if you compare Q1 2025 with Q4 2024.

See IMF Country Report No. 25/219 (August 2025), p. 10, footnote 10.

In retrospect, it might not have been the best sartorial choice. But this was 2012, when wearing a suit and tie was considered a show of respect to the other party.

https://open.substack.com/pub/thiagodearagao/p/five-ways-cheap-oil-squeezes-the?r=2di31u&utm_medium=ios

I hope that Argentina, in the short to medium term, will emerge out of this mess much like post-Communist Poland: https://www.realclearmarkets.com/articles/2024/07/24/argentina_can_grow_by_following_the_poland_growth_model_1046708.html