Why do countries post collateral on their debt?

It usually can't be seized short of invasion, but there is a point to it

Sovereign lending and Chinese debt imperialism is back in the news! I mean, with the American election, two large-scale interstate wars, at least seven major civil wars, and the growing threat that AI will utterly up-end our society, plus the American League Championship Series and other important-to-sanity news fluff, sovereign debt is pretty far down in the news. But it is in the news! Or at least back in the news, since the main story is from last year. Anyway, my favorite blogger, Noah Smith, tweeted about it.

So is Chinese debt imperialism a thing?

TLDR: China really does try to use legal mechanisms to insure that countries repay their debts. But those legal mechanisms only work with international cooperation. Lose that, and they lose their bite. They don’t allow China to “take” Ghanian bauxite reserves, not without an invasion. But countries like Ghana will still remain vulnerable to Chinese “yuan diplomacy,” since default has costs.

The best way to protect against that, paradoxically, is to get Chinese foreign direct investment. Give ‘em a financial stake in the health of your export industry, and you’ll give ‘em incentives to go easier on the debt.

China and Ghana

The Republic of Ghana might default on $1.7 billion of debt owed to the Chinese government. The contracts allow the Chinese to seize Ghanian tax and royalty revenues from the production of cocoa, bauxite, oil, and electricity. (The details can be found on page 20 of the IMF’s Seventh and Eighth Review of Ghana; you can find other details of the loan in this magisterial database put together by Anna Gelpern, Sebastian Horn, Scott Morris, Brad Parks, and Christoph Trebesch.)

How would China “seize” the revenues? The People’s Liberation Army Navy is getting stronger all the time, but it’s really not about to blockade Ghana in this decade. (Maybe in the 2030s.) So what’s stopping a future Ghanian parliament from just telling the Chinese to take a hike?

Well, the Chinese could sue the Ghanian government under Article 293 of the Ghanian constitution. That might even work. But I doubt the Chinese are counting on it, not because Ghanian courts are dishonest or politicized, but because its not clear that Article 293 covers debt default (its equivalents in other countries do not) and in extremis Parliament could amend the constitution.1 Ghana’s internal institutions aren’t what makes collateral credible.

External enforcement

Rather, these agreements rely on external enforcement. Ghana signed an agreement with Sinohydro (a Chinese construction company) for $1.7 billion to build roads. The loan is made over 15 years at an adjustable rate of SOFR + 2.8% interest + 1.2% fees. Ghana pays an upfront fee worth 7% of the loan value and pledges income from future exports of alumina in return.

The agreement is enforced via an overseas escrow account. Ghana pledges to keep two installments ($142m) in an offshore account. In addition, all export revenues from bauxite and alumina will go through that account, which China can seize in event of nonpayment. The theory is that foreign courts would not allow the country to receive payment for the commodities via another channel. Doing so would open the country to lawsuits that would destroy its ability to borrow overseas; it would also make buyers vulnerable and then force Ghana to accept large discounts on the price it received for its alumina.

These kinds of contracts are pretty common for non-sovereign debt issuers like the Detroit or Rome (the one in Italy, not the town in New York) or the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. They were also used a lot in the 19th and early 20th centuries, although as Marc Flandreau, Stefano Pietrosanti, and Carlotta Schuster showed in a 2024 paper, the main reason for those tools was to force governments to disclose fiscal data, not to create a revenue stream that could be somehow seized in British courts.

Pretty weak imperialism

But still. First, a hypothecated revenue stream is not the same thing as “seizing the raw materials.” China won’t be taking control of Ghana’s bauxite mines. Second, the whole thing depends on the cooperation of the United States. Congress could simply pass a law allowing U.S.-based buyers to purchase Ghanian alumina regardless of source.

Finally, as of right now Ghana doesn’t produce any alumina. It did produce 959,601 tons of bauxite last year (page 26). But that is worth maybe $40 million, less than one loan payment. Now, Ghana has a plan to expand bauxite production, construct an alumina plant, and expand its aluminum smelter. That should ultimately get around $2.4 billion in gross export revenue (although don’t forget that production has costs) which China could potentially mess with if Ghana defaults.2 But in essence the Chinese are banking on Ghana’s success.3

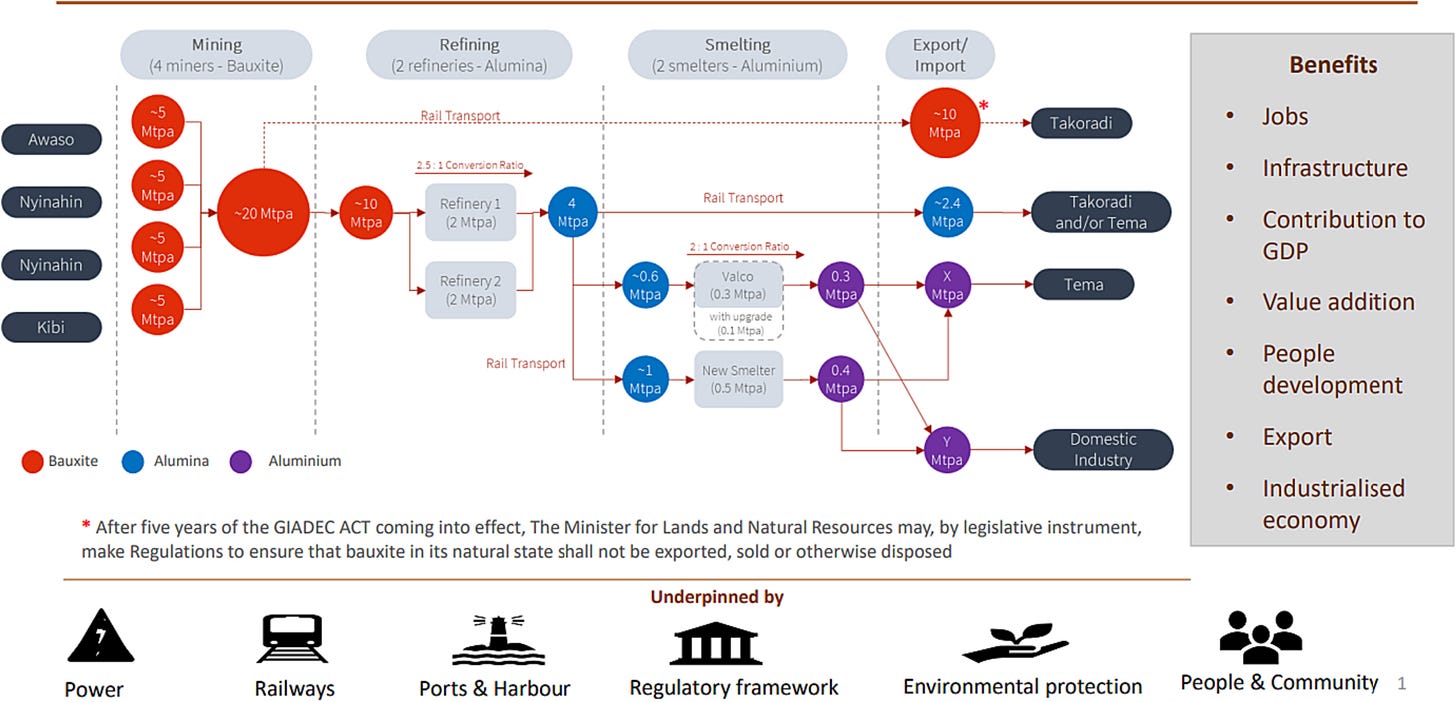

Here is a schematic of Ghana’s plan to expand the industry over the rest of the decade:

In short, right now Ghana doesn’t have the resources to make China’s “collateral” anything more than theoretical. If in the future it does produce enough to fill the collateral accounts, then China will be able to seize those accounts. China will also be able to legally cut off Ghanian aluminum revenues … but only if the U.S. and European governments cooperate. (It would only take one to render the scheme useless.) Otherwise, Ghana could come up with alternative payment mechanisms.

So what’s the advantage of requiring collateral? Well, basically the same one that Flandreau et. al. found for the 19th century: the arrangements force Ghana into fiscal transparency. That’s not nothing when you’re a big lender.

But this is China and China is big

But China would have other options to punish Ghana because this:

China dominates the global bauxite market. The PRC could just boycott Ghana, no need for any legal legerdemain. But would that work? On the one hand, that didn’t work against Australia when China decided to boycott Australian coal:

On the other hand, China doesn’t dominate the world coal market the way that it does bauxite. The Chinese could throw Ghana under the bus. Even after Ghana’s planned expansion (if it happens) the country would be a small enough producer that China could credibly do that.

Ghana could lure China into an empire trap, but doesn’t seem to be

In this, China would be taking a page out the American playbook. The United States used the threat of boycotts to keep both the Porfirio Díaz regime and its revolutionary successor in line. But American trade threats failed to protect American bondholders: the U.S. owners of the Mexican mines and oil fields did not want to sacrifice the profitability of their enterprises on behalf of Wall Street coupon clippers. (I wrote a book about this.)

Erstwhile Chinese debt imperialism would face the same problem: the interests of Chinese creditors would come into conflict with the interests of Chinese investors in the Ghanian industry.

Ghana’s problem is that, well, the Chinese-owned Bosai Minerals Group has sold its holdings to local investors. And its partnering with European companies to build refineries. That would leave the only PRC interests in the country as (a) bauxite users in China, and (b) creditors. Group (a) can get bauxite elsewhere. Which would leave Ghana hanging …

Only there’s no need for “collateral” or anything else. The threat of doing to Ghana what the PRC tried to do to Australia would be enough.

The lesson, paradoxically, is that getting more Chinese FDI might just make a small country less vulnerable to Chinese debt diplomacy. The tail, you see, can wag the dog.

This is not to imply that the Ghanian court system doesn’t have serious problems.

Ghana has signed an agreement with a Greek company to construct an alumina refinery. It also plans to produce 20 million tons of bauxite, of which half will be exported and the rest used to to make alumina and aluminum. Alumina is currently getting north of $500 per ton, although that varies quite a lot, and aluminum is in the $2,000 per ton price range.

Duke University published a decent study of the deal, although you need to go to the footnotes to get the real data. Terrence Neal, “The Environmental Implications of China-Africa Resource-Financed Infrastructure Agreements: Lessons Learned from Ghana’s Sinohydro Agreement,” Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions (March 2021).