What was the Maximato?

Applications to the present situation will be left for the next post

This post began as a commentary on the relationship (such as we can guess) between President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum of Mexico and her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, otherwise known as AMLO. Will she be a puppet of the outgoing president or take the country in her own direction? Or something in between?

The question invited comparisons with the Maximato in 1928-36, when Plutarco Calles ruled (or tried to rule) from behind the scenes as the “Supreme Leader,” sometimes holding a cabinet post but usually holding no position at all. (See here, or for a very subtle mockery of the idea, here.)

But what was the Maximato? Did Plutarco Calles really rule the country without holding formal office, a la Deng Xiaoping after 1989?1

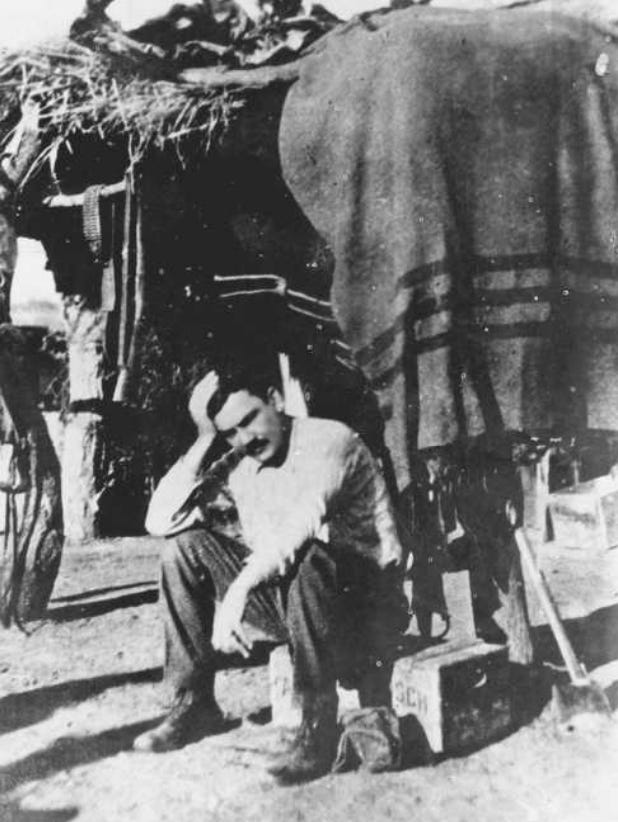

Plutarco Elías Calles, el Jefe Máximo de la Revolución

When I was a young man, el Jefe Máximo de la Revolución fascinated me. Along with Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Calles became a bit of a personal hero. Well, “hero” is the wrong word … Calles was no Neil Armstrong or Abraham Lincoln or Audie Murphy. He wasn’t even a Joe Namath or Reggie Jackson. Calles neither virtuous nor someone you should want to emulate. But I had to admire the man. Kind of like a revolutionary Meyer Lansky to my teenage mind, to name another childhood hero whom I felt kind of bad about admiring.

Why did I find Calles romantic? Well, think about it. An angry young man who hated his dad, he took his aunt’s married name as his own.2 He then becomes a schoolteacher, a hotel manager, and a failed farmer — headed to total obscurity — until the Mexican Revolution starts rolling in 1910. He’s appointed a town mayor by a revolutionary governor, winds up in the armies of so-called “Constitutionalists.” He’s a total wreck as a combat officer, where U.S. military intelligence reports him as “weak, vacillating, and not fond of fighting,” which is basically a paraphrase of what the fellows monitoring my own attempts to command troops in U.S. Army tactical training exercises said about me.

I think you can see why I felt a bond.

Where Calles shows he’s brilliant is logistics … broadly construed. The man could organize a supply chain, yes, but that wasn’t his genius. No, his skill was in raising resources by any means necessary. He confiscates cattle from opposition landowners and manages to sell them in the United States at twice the market price. He works connections in Arizona to get all sorts of everyday merchants to pretend, I don’t know, that he’s just a nice teacher man and of course there’s no problem with the Neutrality Act when he wants to buy massive quantities of clothes. Or ammunition. Or an airplane that he snarfles out of an impound in Arizona on force of character and later uses to bomb enemy positions.

In October 1914 the man realizes that technology has moved war from the kind of glorious charges and manuevers that really didn’t work for his personality to the kind of fight he could win. We’re two months into the First World War and Calles, charged with defending the town of Naco, gets it that trenches and barbed wire will totally make the place impregnable against that dashing 19th-Century combat that he was never any good at. The enemy massacres itself over the course of 107 days.3 Our boy cements his reputation and become governor of his home state with the slogan, “Land and books for all.”

He then plays off a whole bunch of conflicting interests, raises taxes on the copper mines (and makes the Americans like it!), passes reforms that give women equal rights within their marriages (including the right to leave it) and in return insists that women to volunteer to fight in the Constitutionalist Army.4

Calles’s obvious skills get him to become Álvaro Obregón’s right hand man. Obregón then becomes president in 1920 in what’s basically a military coup. “Elections” are held, Obregón ratifies his coup. Then, in 1923, Obregón makes it clear that he’s picked Calles to succeed him when Obregón’s term ends in ‘24.

The De la Huerta Revolt

Treasury Secretary Adolfo de la Huerta was not happy to learn that Calles had received Obregón’s “dedazo.”5

De la Huerta, and his military backers (who all had presidential aspirations as well), therefore declared against the government. The rebellion was not, however, just about the presidential succession. Also at stake was the question of the implementation of the agrarian reform specified in the Constitution of 1917. So the rebels pulled in support from Mexico’s largest landowners.

Two-thirds of the army joined the rebellion. These included 8 of Mexico’s 35 military zone commanders and 25 other lesser ranked generals. The conspirators included Guadalupe Sánchez, the military zone of Veracruz, Enrique Estrada, the zone commander of Jalisco, and Fortunato Maycotte, the Oaxaca zone commander.

General Maycotte’s story provides a good sense of how little control Obregón had over his own army. On hearing of the rebellion, Maycotte rushed to Mexico City where he pledged his allegiance to Obregón and asked for 200,000 pesos and war material in order to go out into the field and crush the rebels. Once outside of Mexico City with the cash and the arms, Maycotte then declared for the rebellion.6

The De la Huerta Rebellion came very close to success. Two-thirds of the army went over the rebel side. Those elements of the army that did not declare against Obregón were of questionable loyalty.

Obregón was saved by three factors — and Calles played no small roll in helping him capitalize on each one. First, the rebels were internally divided. As one contemporary observer, Ernest Gruening, put it: “The rebels could have won had they been capable of loyalty to each other for even a few weeks. But hardly in the field each general began knifing the next, fearful that a victory might give a rival the pole in the presidential scramble.”7

Second, Obregón and Calles were able to mobilize worker and peasant militias to face down de la Huerta’s numerically superior army. The worker militias were organized by a national labor union called the CROM. The peasant militias were lead by agrarian warlords who had emerged from the Revolution and who had succeeded in obtaining land for their followers. With Calles’s help, Obregón armed these peasant militias and motivated them by claiming that the rebels, if successful, would take back the land that the peasants had received from the government. The end result was that the militias could take over garrison and combat service support functions, allowing the government to put more soldiers into the field than the rebels despite the fact that most of the uniformed forces had defected.

Third, they got U.S. support. Once the rebellion started, Calles went out of his way to assure the Americans that he had no intention of breaking any of the agreements that the Obregón administration had signed or violating the property rights of any American companies operating in-country.8 De la Huerta didn’t help himself by raising money via “loans” taken out at gunpoint from American-owned companies.9 The Coolidge administration scrupulously enforced the Neutrality Act against the rebels but allowed government forces to transit American territory, bypassing rebel-held territory. The U.S. also agreed to sell the Mexican government 1.3 million dollars worth of arms, consisting of eleven airplanes, 33 machine guns, 15,000 Enfield rifles, and five million rounds of ammunition.

This was neither a huge sum against Mexican annual government revenues of 141 million dollars nor a game-changing quantity of ordinance. The game-changing effect was on rebel morale. After all, there was no reason to believe that $1.3 million was going to be the end of U.S. aid, especially considering that half of the munitions were provided on credit.10 Once the U.S. threw its weight behind the government,

De la Huerta, realizing that the situation was deteriorating, escaped to exile in the United States. The generals who supported him were not so lucky: Obregón ordered the execution of all captured rebel leaders above the rank of major.

Calles becomes President

In ‘24, Obregón steps down (as per the Constitution) and hands things off to Calles, with every intention of coming back in ‘28. Moreover, the two of them (with the legislature under their control) amend the constitution to extend the presidential term to six years, insuring that Obregón will be in until (at least) 1934.

Calles’s presidency was almost consumed the Cristero War. Calles decided to enforce Articles 3 and 130 of the Constitution, which banned religious education, stripped clerics of freedom of speech and association, and effectively nationalized most Church property. This triggered a guerrilla uprising by angry Catholics in 1926. Negotiations commenced in 1927, with a great deal of American involvement, but the conflict wouldn’t end until 1929.

Calles as the Maximum Leader

Obregón won the (completely rigged) 1928 election, but a Cristero terrorist killed him in July 1928 right before he could take office. With Obregón dead, Calles needed to pick a successor and prevent a resurgence of fighting among the generals and retired generals who had emerged from the revolutionary violence. He also needed to negotiate an end to the Cristero War. Mexico had no vice-president, likely because nobody really trusted anyone to hold a post guaranteed to make you President in the event of the incumbent’s death. Instead, Article 84 of the Constitution gave Congress the responsibility for choosing an interim president and calling new elections to “as far as possible coincide with the date of the next election of Deputies and Senators.”

To make the pick, Calles negotiated more with the military and dissident generals than with Congress. Calles sat down with the generals in Chapultepec Castle and got them all to promise that they wouldn’t seek the presidency — nor would Calles. (It helped that the Constitution nominally prevented Calles from serving a consecutive second term.)

Interior Secretary Emilio Portes Gil emerged as the consensus candidate. Congress appointed him to serve until a new election could be held on November 17th, 1929. Acting President Portes does not appear to have been Calles’s puppet. He had his own support base in Tamaulipas and among various generals. Calles opposed land redistribution, for example: Portes got funding reinstated despite the Jefe Máximo’s opposition. He eventually distributed 1.2 million hectares to more than 100,000 families. Moreover, when Calles started to lean towards appointing Aarón Sáenz to replace him, Portes openly opposed Sáenz and got Calles to appoint Pascual Ortiz Rubio instead. This was particularly impressive, considering that Sáenz was Calles’s business partner and the brother of his son’s wife. And for what it’s worth, in later life Portes was adamant that he was his own man.

Calles had some leverage over Portes Gil, but Portes was not a puppet. Calles’s influence came from four sources — you could say it was overdetermined.

He’d picked Portes. And the two of them knew each other and were colleagues. That goes a long way.

Portes Gil entered office a lame duck. He become Acting President on December 1st, 1928. The elections were scheduled for November 17th, 1929. That gave him 351 days to get anything done. 432 days if you count time until the official transition. This is not a lot.

The creation of the National Revolutionary Party (PNR, after its Spanish initials). After Obregón’s assassination, Calles wanted to head off the internecine conflict that had characterized Mexican history since the Revolution. On November 21, 1928, Calles gathered most of the potential grandees and revolt leaders in his own to create a talking shop that would attempt to adjudicate disputes among the various revolutionary personalities and factions. The PNR was not a political party the way we might think of it. There were no grassroots or patronage machines at first. Rather, it was a talking shop to which fake regional parties — the creations of regional caudillos — sent delegations. We shouldn’t exaggerate this, but it did place some limits on Portes Gil.

Portes and Calles had to face down a full on military revolt in 1930, after the PNR picked Ortiz Rubio as its candidates. Dissident generals declared a revolt and took at least one-third of the active duty army with them, under General José Gonzalo Escobar. It took several weeks of fighting and 2,000 deaths to defeat the rebellion … and it meant that Portes Gil and Calles had to cooperate closely to defeat the rebels.

Pascual Ortiz Rubio replaced Portes, but he had no political base from the start. He gained the presidency in a comically-stolen election, which everyone knew. He immediately became the target of an assassination attempt on the day of his inauguration. Calles became Secretary of War and worked continuously to provoke upheaval in Ortiz’s cabinet. In August 1932, after a hospital adminstration scandal implicated Ortiz’s brother, the jefe máximo publicly called for all his friends to refuse to serve in the cabinet. Within a month Ortiz had resigned. Sadly, the story that he woke up to read about his resignation in the newspaper appears to be apocryphal.

This was when Calles truly appeared to be the puppet master, working behind the scenes.

But was he? His puppeteering was obvious, almost crude, and aimed at a president who was weakened from the start. At the end, Calles appears to have kicked Ortiz to the curb simply because he could. The reason seems more to have been to burn somebody at the stake for the gathering economic storm of the Great Depression rather than to set a warning for future presidents.

Congress appointed Abelardo Rodríguez to the remainder of the term. Calles was still in charge — but less so than under Ortiz. President Rodríguez accelerated land redistribution and indexed the minimum wage to inflation, neither of which Calles approved of. Rodríguez also removed Calles’s preferred Treasury Secretary, giving the position to Calles himself for six weeks before they agreed on a replacement. President Rodríguez later told the American ambassador that he had removed Pani because the finance secretary had tried to appeal to Calles over the President’s head.11

Calles, ever the bureaucrat, pushed back against his waning influence by strengthening the party he ran. First, he managed to reorganize the PNR as a centralized party, and not just a federation of regional parties. Second, he convinced the PNR to support banning the re-election of federal legislators, which would make said legislators incapable of amassing power independently and force them to rely on the party for their next job if they wanted to stay in public life.

These reforms helped Calles retain some authority, but not as much as commonly believed. President Rodríguez assumed more-and-more authority, pressing various economic initiatives of which the increasingly-conservative Calles disapproved. The regional parties had been abolished in name only; local machines routinely disregarded directives from PNR headquarters. These two problems came together in the PNR convention of December 1933. President Rodríguez maneuvered a crony into the platform committee. With the help of local organizations, he got the platform to call for more land redistribution against Calles’s wishes—and Rodríguez then used that platform actually redistribute more land during the remainder of his term, even though the Maximum Leader had declared land reform over back in 1930.12

Conclusion

The story of how Calles reluctantly gave Lázaro Cárdenas the dedazo in 1934 only to be squeezed out and sent into (temporary) exile is well known.13 What is less well known is that the Maximum Leader really didn’t exercise all that much power during the “Maximato.” He received efflusive displays of public loyalty. He obtained and used a very high level of influence. But he only ruled as a puppet master during the short presidency of Pascual Ortiz Rubio — and that was under a rather unique set of circumstances. He never really even cemented control over the political party that he created.

Any lessons for the upcoming presidency of Claudia Sheinbaum are left as an exercise for the reader. Or more likely a future post.

Arguably, after 1982, since Deng held only the vague title of Chairman of the Central Military Commission after that point. Calles also held various cabinet posts and became the

I almost did just that. I am very glad that I didn’t; my father and I reconciled later in life and by the time I passed 30 anyone who met the two of us would have been shocked to think that we had once been almost (but not quite!) estranged, let alone that we’d had an outright fistfight in 1988.

The story here is somewhat more complicated. Federal Army doctrine was actually not that bad or outdated, but this particular Federal Army commander did not know when to quit.

“Dedazo” means “big finger.” As the tradition of having the outgoing President designate his successor gained traction, the appointment became known as “getting the big finger.”

I’m not going to footnote this part because it comes from a book that I co-wrote.

Gruening 1928, p. 321.

You can read all these pronouncements in Calles’s own words in his book, Mexico Before the World, published in 1927.

This kind of thing really pissed off President Coolidge’s Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes. See, for one of many examples, Summerlin to Hughes, 24 December 1923 (812.00/26664).

The fact that the U.S. was selling surplus gave the Coolidge administration a lot of leeway to set the price, implicitly subsidizing the Mexican government.

See Jurgen Buchenau, The Sonoran Dynasty in Mexico, p. 279.

The best source on this period remains Luis Garrido, El Partido de la Revolución Institucionalizada (1982), in this cases pages 158-59, although if you prefer English then I cannot recommend Jurgen Buchenau’s corpus more highly.

Although many forget that the precipitating incident that prompted President Cárdenas to exile Calles was a bomb attack on a passenger train that killed 13 people, including a prominent critic of the Jefe Máximo. I doubt that Calles actually masterminded the bombing, but people forget the background level of political violence in Mexico that lasted through the 1940s.