Exxon, Shell, and the Math of Venezuelan Oil

Venezuela’s taxes break its oil economics

ExxonMobil is in trouble with the Trump administration for telling it that Venezuela is “uninvestable” under current conditions. The President did not like this answer and is threatening to freeze Exxon out of Venezuela. Shell, on the other hand, has declared that it is “ready to go.”

So which one is right?

Well, let’s see.

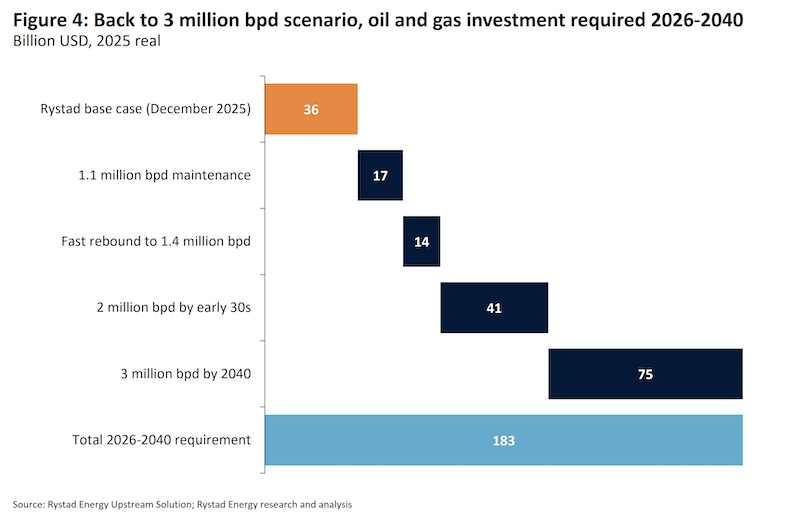

Rystad Energy tried to cost out what it would require to get Venezuela’s output back up to 3 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2040. They estimated that it would require $183 billion in capital expenditures to accomplish that, broken out as follows:

Explained: the field will need $53 billion over 14 years to maintain current production ($36 billion + $17 billion). Additional amounts will need to be invested to get production back up to historic levels.

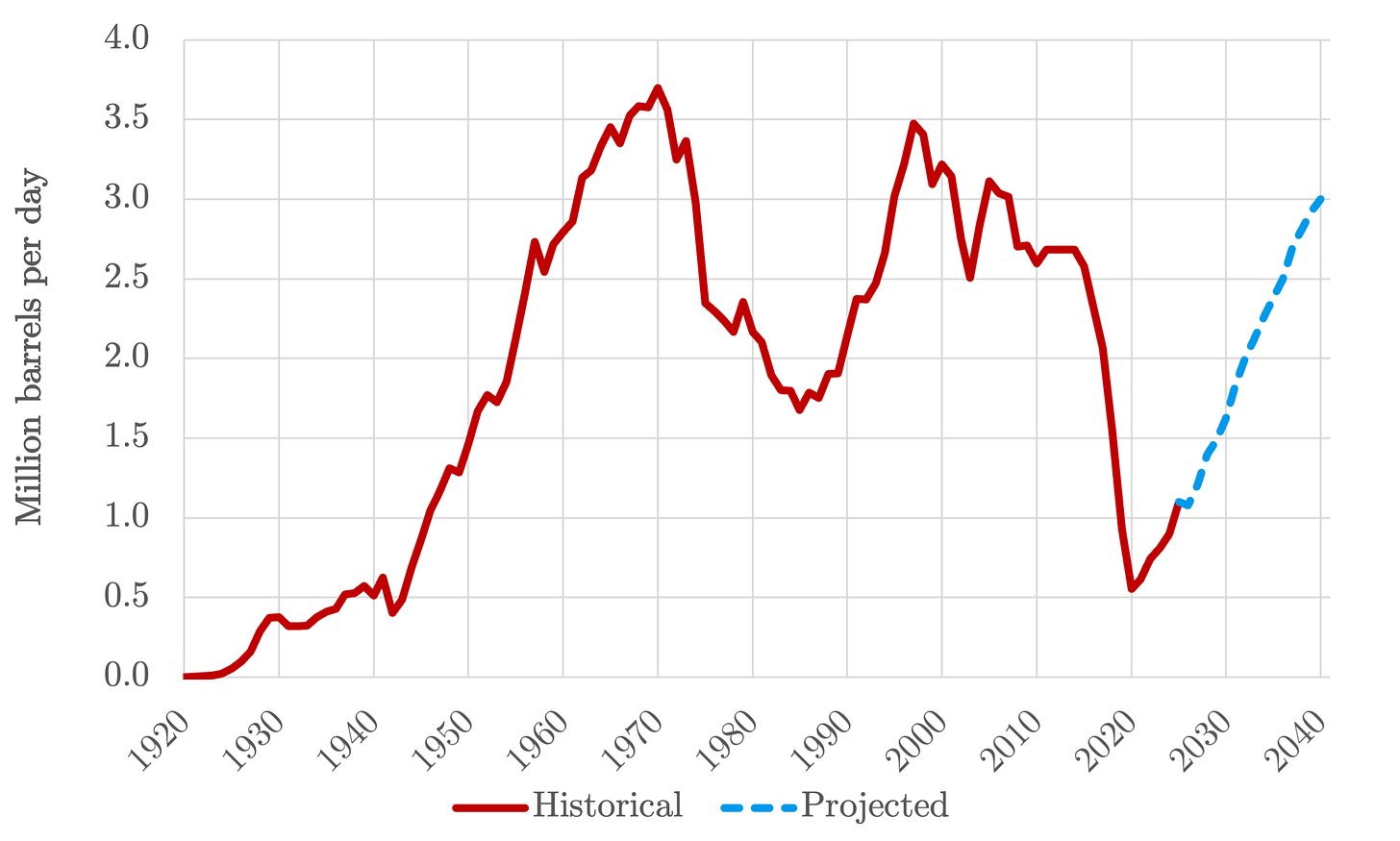

While it is possible that this could happen more quickly than Rystad estimates, it is nonetheless a pretty rapid rate of growth in historic perspective:

We can back Rystad’s capex estimates into a rough annual flow over the period. We’ll only consider the expansion: that is, the $148 billion that needs to be invested in order to increase production beyond 1.1 million bpd, rather than keep existing fields running. Assuming an operating cost of roughly $17 per barrel (this is optimistic, but I’ll discuss below in another post) then you get a flow of expenditures and output that looks like this:

The last line gives the net present value in 2041 of all subsequent expenditures, assuming a certain level of continuing capex to keep production going. You can then use the above data to back out the minimum price per barrel at which the project makes sense for any given discount rate. Let’s run with 12%. That is a relatively low hurdle rate for an oil project in a country like Venezuela. Still, it isn’t unreasonable given how much pressure companies will come under from Washington to expand production. In order to get the equilibrium price, you divide the net present value (NPV) of expenditures by the NPV of the number of barrels that you expect to produce.

That equilibrium price turns out to be $39 per barrel. This $39 figure reflects project economics without any taxes or royalties. Consider it a counterfactual benchmark. Currently, Venezuelan crude is trading at roughly $22 below Brent, which is (coincidentally) around $39 per barrel. And that price is almost certain to rise in the absence of sanctions and legal uncertainty: the historical discount on Venezuela’s Merey blend has been around $7 per barrel, not $22. Even with Rystad’s high capex estimates and a long payoff period — the expansion as a whole won’t generate a positive cash flow until 2038 — investing in the Orinoco appears to make sense on project economics.

To be clear for readers unversed in accounting: this does not mean that the project will fail to earn a return for investors. They still earn a 12% return on their capital. It just means that the payoff is back-loaded.

But to repeat, this all assumes that the Venezuelan government charges no royalties, taxes, or fees. Nothing. Zip. Nada. Which is obviously not the case.

Moreover …

The Bolivarian Republic’s fiscal system is crazy

On paper, Venezuela’s fiscal regime doesn’t look insane. There is a 63.4% combined royalty, production tax, and export charge — that’s 63.4% percent right off the top, not of income. In practice, however, the government generally cuts the combined levy to 40.1%. Then once that is paid, the government applies a 50% income tax rate. Now, that’s a pretty high tax rate — 40.1% off of gross revenues and then half of the remaining profits — but isn’t completely out-of-line for traditional oil projects.

Except that the places that have punitive fiscal regimes like the BRV also have low lifting costs and require low capital expenditures. That does not characterize Venezuela.

So what’s the breakeven price under Venezuela’s system? We can do this quick-and-dirty or we can do it right. Quick and dirty: gross taxes of 40% plus income taxes of 50% means a marginal government share of revenues in the in the 70% range.1 That means that the post-tax breakeven price per barrel (at a 12% hurdle rate) becomes:

Whoa.

Doing it right produces an even higher number: breakeven comes to an astronomical $157 per barrel, assuming that capital expenditures can be recovered through 10-year straight-line depreciation. The gap arises because straight-line depreciation means that capital costs are recouped slowly rather than expensed up-front. That means investors need more cash more quickly to hit the same hurdle rate.

Below are the results of the calculations: the project’s total NPV (including the 12% return) doesn’t go positive below that astronomical oil price.2

In other words, ExxonMobil’s CEO is correct. Venezuela needs a saner fiscal system before anyone will invest. The current Venezuelan fiscal regime is punishing and the risk of expropriation is high, in addition to the already-significant project risk given the terrible state of the fields and facilities.

It is possible to calculate the maximum government share of gross revenues that at any given oil price that will still let the investors hit their hurdle rate. At $56 per barrel, that number comes to about 30%. It will also yield the Venezuelan government about $12 billion per year once production hits 3 million bpd. A royalty of 30% off the top is not unreasonable — in Texas, private landowners generally charge around 25%.3 And, of course, Venezuela could add in income taxes or a sliding royalty scale or accelerated depreciation or all sorts of other things to that would preserve their average share of revenues while making things more attractive for private investors.

But the government is going to have to revamp its fiscal system and the United States is going to have to guarantee that it won’t change in the future. President Trump may not have wanted to hear that news, but it is nonetheless true. I presume that somebody in the State Department is explaining this to Delcy Rodríguez as you read this.

Right?

It actually comes out to 75%, but you can’t calculate the exact number without estimating the breakeven price the complicated way first.

Cash flow is calculated using the actual capital expenditures from the first table’s “capex” column, not the amount that can be expensed for tax purposes that is in the “capex deduction column in the second one.

The standard measure here is “government take,” which tries to measure the government’s share of the project’s economic rents. It takes the NPV of the government’s revenues and divides it by the combined NPV of the government’s revenues plus the project’s free cash flows. I don’t like this measure. For example, at breakeven shareholders and lenders will be happy — shareholders got their hurdle rate and lenders got paid — but the “government take” will be 100% by this measure. That seems misleading, no?

This is an excellent explainer, and the NPV tables make it very easy to understand the numbers involved.

Why is there a negative $9.1 billion cashflow (second table) in the year 2026 though? Not that it would change the results.