The Mystery of Uruguay

No, it’s not “why does the country exist”

Uruguay looms a bit larger than you’d expect in many people’s view of Latin America. It’s the “Switzerland of South America.” It’s the “first welfare state.” It has low inequality and high incomes. And its boring politics have become a regular punchline from Boz of the Latin America Risk Report.1

These views are nothing new. Here’s a discussion of Uruguay from 1953:

I again asked to see slums, sticking to my theory that a worm’s-eye view of a culture is the only one with a true perspective. Mr. Roitman did his best to oblige. Presently I said to him, “When do we get to where the poor people live?”

He stopped the car. “This is it.”

I looked around and said, “No, no, I mean the really poor people,” then explained what we had seen elsewhere.

“But these are the poor people. These are the poorest people in Montevideo.”

I looked around me again and was tempted to call him a liar. These were not tenements nor the hovels of the poverty-stricken; these were small and simple single-family houses, each with its flower garden, quite evidently the homes of self-respecting lower-middle class. I already knew that Mr.Roitman was proudly patriotic and I suspected that his national pride had caused him not to show me the seamy side of his city.

Unsatisfied, I checked on it later. Señor Roitman was right; these were their “poor.” Uruguay has no extreme poor. It is a welfare state that works, without, so far as we could see, the dreary drawbacks of other welfare states. How they have managed this I do not know, for I have seen other welfare states which appeared to have much the same sort of legislation and the results I did not like at all.

I just got back from Uruguay in 2024, and I have to say that the above is not my impression.

In fact, if you showed me pictures of Buenos Aires and Montevideo and asked, “Which city has just experienced two decades of recurrent economic crises, political instability, mass demonstrations, populist government, pension confiscations, several years of high inflation and a recent bout with hyperinflation?” I would pick the wrong one. Montevideo is the city of many obviously troubled homeless people on the streets; Montevideo is the city of run-down buildings; Montevideo is the city where the government shut down the commuter rail system leaving only a motley collection of buses.

And that’s the mystery of Uruguay. For a place as evidently well-run as this country, why isn’t it doing better?

But first, some historical perspective

Why did the visitor to Uruguay in 1953 think of it as a rich country? Essentially because it still was at that point. In the 1950s, Uruguay’s GDP per capita was roughly half the United States, putting it on a par with France. Admittedly, France in 1950 was still suffering from the after effects on the Second World War, but it was nonetheless considered a rich country. So it makes sense that American visitors to Uruguay would think of the place in the same bucket. The below picture compares Uruguay to a country most American observers would have thought of as “rich” in 1953 (France) with a country that would have seemed “poor” (Mexico).2 On this very broad-brush measure, Uruguay in the early 1950s is closer to France than to Mexico.

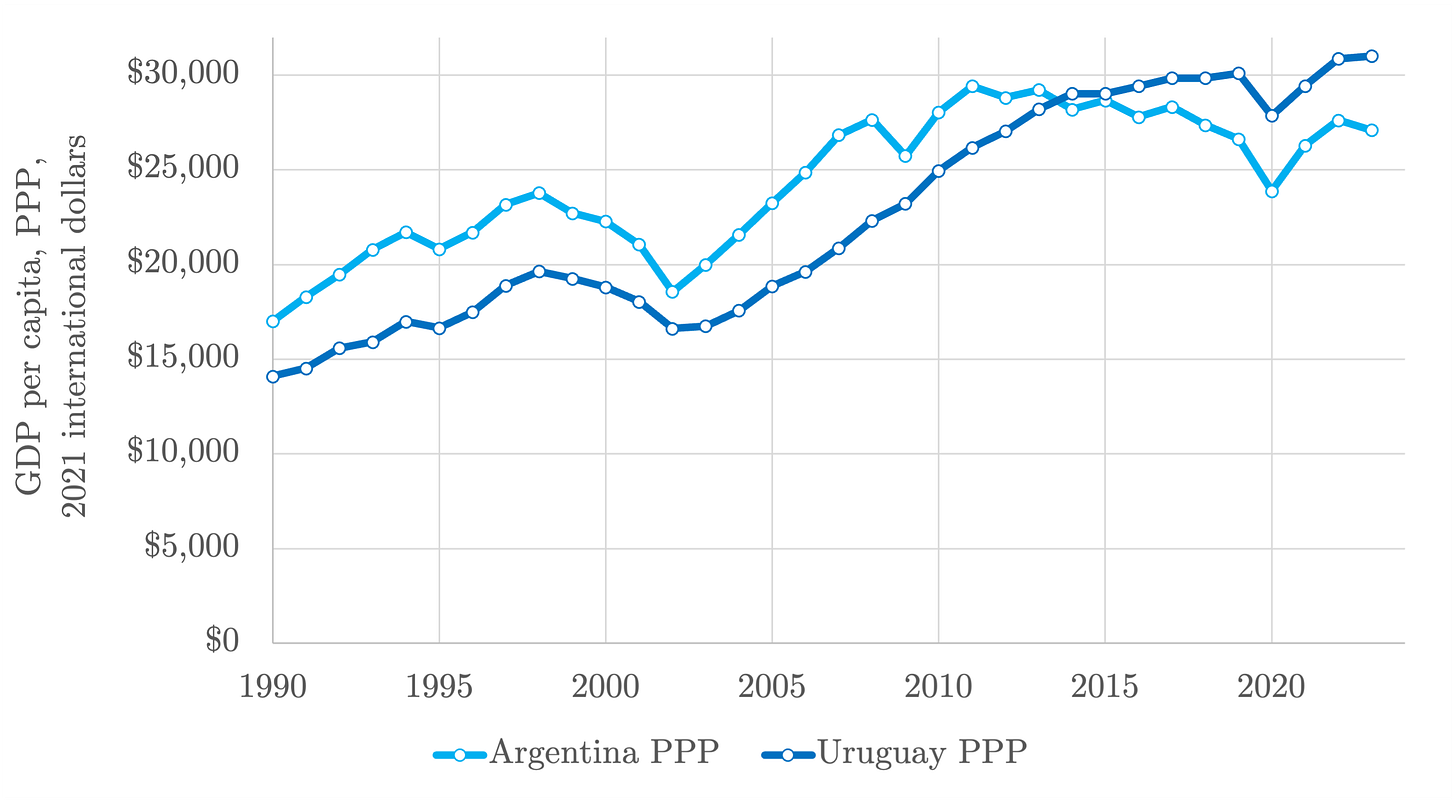

But today it is not closer to France. The country has converged downwards to Mexico. Moreover, it has failed to diverge from Argentina. Both countries exited military rule around the same time (1983 for Argentina and 1985 for Uruguay). Since then, however, Argentina experienced an ill-fated experience with a currency board, a banking collapse of Great Depression scale, a cut-off from international capital markets, and fiscal mismanagement of such colossal scale that inflation soared into the triple-digits. Well-run little Uruguay had none of this. And yet …

All Uruguay managed to do was close a long-standing (albeit relatively small) gap between the two countries. It didn’t substantially outdistance the giant across the river, despite doing everything right domestically and benefiting from the same favorable external environment. The “net barter terms of trade” measure the price of a country’s imports relative to the price of its exports. The below figure shows the figures for both countries. Uruguay’s boom developed a bit more slowly but was more-or-less the same magnitude:

Uruguay did avoid the economic mismanagement of the last decade … but all that meant was that the country stagnated instead of declined after 2015. And even now, the Argentine advantage on paper is small, and disappears on the ground when you compare Buenos Aires (including its suburbs) with Montevideo.

Uruguay has other problems, many of which are equally mysterious for a country as apparantly tranquil and well-run as Uruguay.

Which leads us back to the mystery: why isn’t Uruguay much more prosperous than it is?

To which you should subscribe immediately!

We disagree with Noah Smith that GDP/capita is a great indicator of relative living standards. One of us is on the board of the Maddison project: rebasing the deflator and purchasing-power adjustment from 1990 to 2011 bumped down a lot of countries relative to the United States and to eachother—under the old numbers, Uruguay was doing a bit better than France in 1953 and significantly outdistancing Argentina; whereas the new numbers show it doing a bit worse than both France and Argentina. Which is “right”? Nobody can say. In addition, distribution matters: Uruguay had a relatively equal income distribution but a rather low labor share of income in ‘53—how does that shake out? That said, GDP per capita is the quickest and dirtiest single number that we have and its level does more-or-less correlate with the things that really make a country seem rich.

The homicide rate been 11.5 also does not fit the "Switzsrland in LA" discourse. The rate is much worse than it looks since median age is higher in Uruguay than elsewhere https://insightcrime.org/news/insight-crime-2023-homicide-round-up/