The Dutch election of 2025 ...

... does not mean what you think it means

TLDR for short attention spans: the Dutch electorate did NOT move left in the latest election. If anything, the reverse. End. But since it’s personal for me, I’ll write a longer version.

As many of you may know, the Nobel Prize in Economics was won by a short Dutch Jew whose last name starts with “M” and first name ends in “oel.” I’d like to thank the committee on its very wise choice of Joel Mokyr.

Coincidentally, I also happen to be a short Dutch Jew with a similar first and last name.1 Which means that I voted in the recent Netherlands general election.

The lower house of the legislature is elected using an extreme form of proportional representation; the minimum threshold to get a seat is only 0.67% of the total vote.2 Which is to say that a party can get in with just a hair over 71,000 votes. Combine that with very easy ballot access — you can get on with a refundable deposit of only €11,250 — and you have a fragmented system that generally leads to very boring coalition governments.

For that reason, Dutch elections typically pass by without anyone noticing or caring outside the country. That is a good thing — elections are most exciting when big things are at stake. No one should want their well-being to hinge upon an election outcome. Elections can also be exciting when they’re dysfunctional or ridiculous, but given how important governing is, no one should want that either.

Recently, however, that has not been the case. Dutch politics has been unpleasantly exciting. The reason is Geert Wilders.

The 2023 election

In the last election, the Freedom Party (PVV) came in first place with 23% of the vote. The Freedom Party is not boring. It’s the opposite of boring.

The Freedom Party is headed up by Geert Wilders, the kind of person that my mom would have called a “character.”3 Wilders’ father, like my mother, survived the Nazi occupation and was left with a deep-seated revulsion at all things German. (Also like my mother.) Wilders’ mother was a multiracial refugee who fled Indonesia at independence for a mother country that she’d never seen. He split with the more moderate squishy-libertarian People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) over the possibility that Turkey might be let into the European Union. He then became increasingly anti-immigration and anti-Islam as time went on; by the last election, his party wanted to ban the Koran.

Nobody else wanted Wilders to become Prime Minister — Wilders didn’t seem to want Wilders to be Prime Minister — so after nine months of negotiations you got a weird coalition with the Freedom Party in it but not in it and a guy named Dick Schoof appointed Prime Minister. Here are the parties that made it up:

The Freedom Party. ‘Nuff said.

The People’s Party. Long form: “People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy,” and who could disagree with that? (Nobody in the Netherlands calls it just the “People’s Party,” but I will because it sounds good in English.) This is a boring center-right outfit that managed to put up the same guy as Prime Minister from 2010 to 2024. I think it has principles. At least that’s what its website tells me.

The New Social Contract (NSC), which was, as its name implies, new. Its leader, Pieter Omtzigt, walked out of the party I usually vote for in a huff over something or other. The NSC’s ideology could have been produced by a random number generator, which may be a good thing. Since I’m also an American, I can’t get behind its demand to create a Constitutional Court.

The Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB). In order to explain these guys, I’m going to have to explain the Only-in-Nederland nitrogen controversy, which I’m gonna punt to the bottom of this post.

This rickety thing was destined for collapse, which it finally did between June and August of this year. The collapse started when the Freedom Party insisted that the Netherlands deny all future asylum requests and send all resident Syrians home since the war was officially over. The People’s Party found some principles and said “no,” so the Freedom Party left the coalition. A new election was called for October 29th, 2025.4

The 2025 election

The election result caused celebration across the center-left in Europe; it even managed to penetrate American insularity. The Freedom Party lost its plurality, passed by the center-left D66. D66 was fairly radical when it was formed in 1966 — that’s where its name comes from — but now it’s boringly liberal.5 If the United States had a multiparty system it’s the kind of thing you’d expect to emerge from Marin County or Bethesda. On the center-right, the “We don’t need no stinking beliefs” People’s Party got 14% and the truly boring party, the Christian Democrats (CDA), revived to win 12% of the vote after a near-death experience in 2023.6

A return to normalcy! A chicken in every pot! A good €1.68 cigar!7

Uh, no.

Hoe meer dingen veranderen, hoe meer ze hetzelfde blijven

It sounds better in French, I have to admit. (And even worse in my broken Dutch with the New York accent.) Nonetheless, it is true — everything seemed to change in the election, but in reality not much changed.

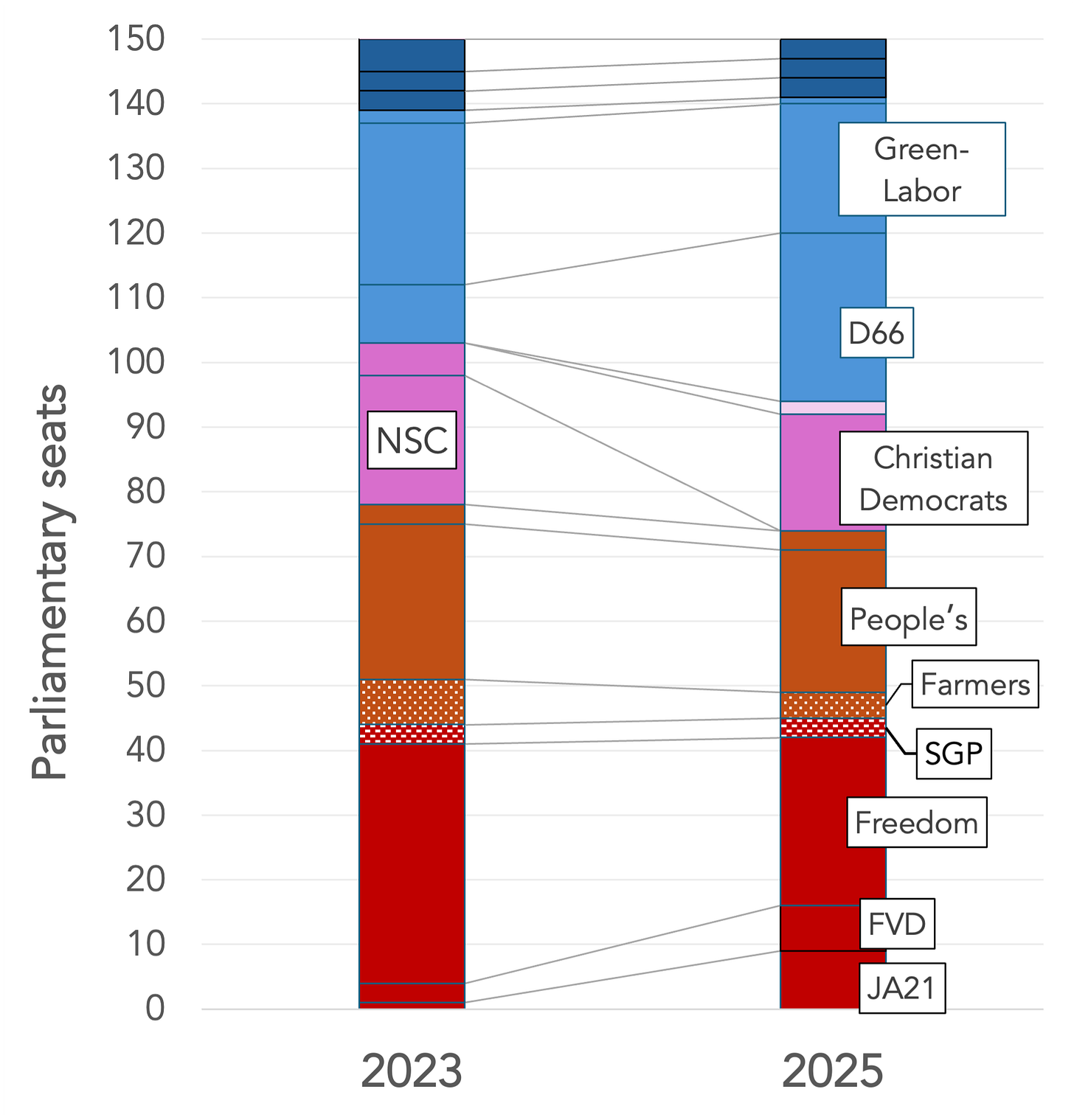

In the above chart, I tried to order the parties with left parties at the top and right parties at the bottom. I used American conventions to color-code center-left parties in blue, centrist parties in purple, center-right parties in orange, and populist right parties in red. (The ratings are subjective.)

You can see that the Freedom Party lost ground to even more right-wing outfits.8 Overall, the populist right gained a seat. (I put a fundamentalist Christian party called the SGP in lighter red. It isn’t really like the populists, but it did not lose seats either.)

D66 didn’t take votes away from the populists; neither did the Christian Democrats. Rather, two shifts determined the election. The first was the collapse of the NSC. Its voters gravitated to two established parties: D66 and the back-from-the-dead Christian Democrats. D66 also grabbed votes from the Green-Labor coalition. The second was a contraction in support for the Farmers Party (BBB), which occupied a strange issue-space in the Netherlands’ fractured political system.

In short, the center-left prospered at the expense of the center because the NSC collapsed. Voters defected from the Freedom Party, but because they didn’t think it was radical enough, not because they saw the progressive light.

Which brings us to the BBB.

The only-in-Nederland nitrogen crisis

The BBB arose in reaction to the Dutch government’s decision to limit “nitrogen” emissions. Urea-based fertilizer and manure on farms release ammonia and nitrous oxide, which can harm natural habitats. Farms in the Netherlands use a lot of fertilizer.

In 1992, the European Council passed the “Habitats Directive,” which required national governments to declare particular areas as “special areas of conservation.”9 The directive sat around unnoticed by most Dutch voters people until 2019, when the Netherlands’ highest court (not the European Court, this is a domestic story) ruled that the government had failed to protect a bunch of special areas from nitrogen runoff. So the government looked around, realized that dairy farms produced 80% of the nitrogen compounds but only employed 15,000 workers and generated just 1.2% of GDP. Deputy prime minister Johan Remkes (of the People’s Party) duly declared that “drastic measures” would be taken to reduce the emission of nitrogen compounds by buying out and shutting down dairy farms.

Uh oh.

Farmers were outraged. Giant tractors drove right into the Hague and broke into a park near Parliament. In Groningen, a town I’ve been to quite a bit, angry farmers invaded the provincial hall. The anger and demonstrations went on and on; the farmers blocked roads with piles of manure; in July 2022, police officers resorted to firing shots in the air in order to get angry farmers to disperse.

In 2022, Donald Trump got into the act:

“Farmers in the Netherlands of all places are courageously opposing the climate tyranny of the Dutch government. Can you believe that? Which wants to dramatically cut Dutch farm production despite growing food shortages. We stand with the peaceful Dutch farmers who are bravely fighting for their freedom.”

The result was the Farmer-Citizen Movement (BBB), and to a lesser extent the NSC. In the Schoof government, the BBB managed to get the buyout program declared “voluntary” and push back the target date for emission cuts from 2030 to 2035.

The controversy might result from a European directive, but at the end of the day the policy decision lies with the Hague, not Brussels. Most European countries, Germany included, have set rather more lenient standards than the Netherlands. And while some appear to be in violation of the directive, European enforcement has been deliberately slow. As of April 2024 the Commission had pursued twenty actions against states for letting too many nitrates get into water. But as far as I could find in the E.U. databases, only one of those, Case C-298/19 against Greece resulted in a fine.10 And that fine amounted to a less-than-overwhelming €3.5 million.

In other words, the Netherlands could have taken a professional foul! A professional foul in soccer is where a player decides that taking the penalty for a foul is better than letting the opposing play succeed. I’m a federalist and I don’t think that the European Union should work this way, but it does work that way, and given that there’s no reason the Netherlands shouldn’t play by the rules as they are.

The farmers are right to blame the Hague rather than Brussels for the imbroglio. And their voters were entirely rational to defect from the BBB given the BBB’s failure to adequately address their concerns.

The election has consequences but …

… they are not what most of the foreign commentariat thinks they are. D66 and the Christian Democrats are currently deep into coalition talks, but I will be surprised they choose to loosen immigration laws.

The Schoof cabinet didn’t collapse because the other parties rejected Wilders’ demands for stricter asylum rules. It collapsed because Wilders demanded that the government immediately sign off on them instead of submitting them to Parliamentary debate. In other words, he lost votes because he didn’t take governing seriously.

It didn’t help that Wilders chickened out from a debate during the campaign because he putatively received death threats from Belgian jihadis. This didn’t go over well, especially since the head of the People’s Party, Dilan Yeşilgöz, has faced death threats almost permanently because of her last name, and she didn’t suspend campaigning.. Given his failure to get his objectives signed into law, it is no surprise that Wilders’ supporters defected to further right parties.

In the medium term, this is good for progressives. The Freedom Party discredited itself as a credible governing partner. It also discredited Wilders personally.

In the longer term, however, the Dutch government will need to identify and address the root concerns of far right voters or risk a worse reaction in the future. Support for the far right is not diminishing.

The center-left may have won, but they face the electorate they have, not the electorate that they wish they had.

My mother picked my first name to be as non-Semitic as possible, “Christian” being a bridge too far for Pop. That is a true story. I could’ve been Christian Maurer, as if I don’t already have enough trouble every time I go to a new shul.

The Senate has the power to veto legislation; it can neither amend nor propose. It’s indirectly elected by the legislatures of the provincial governments, including the Caribbean territories. Each province gets a number of votes in the electoral college proportionate to its population. Those votes, in turn, are divvied up by party proportionately to the number of votes each party received in the relevant provincial legislature.

It’s not a compliment.

There was even more drama on October 22nd, when the People’s Party and the Farmer-Citizen Movement decided that they just had to do something about Israel’s war in Gaza and the NSC responded with a hard “no.”

I mean “boringly liberal” as a compliment, by the way. Boring is good.

The CDA collapsed to only 3% of the vote in ‘23, down from 10% in ‘21 and 35% in the glory days of the 1980s. And even that is an understatement, since the parties that united into the Christian Democratic Alliance in 1977 regularly pulled in outright majorities until the early 1970s.

In 1914, Vice-president Thomas Marshall famously said, “What this country really needs is a good five-cent cigar.” That remains true everywhere. In 1914, five cents (U.S.) bought you 12.3 cents (N.L.). Adjusting for inflation and currency changes, as calculated in Ljungberg (2024), that’s €1.68 today. You can actually get a decent stick in Nederland for around 6 euros, but not €1.68. Yes, I’m a nerd.

The Forum for Democracy (FVD) has traveled a trajectory not unlike the Alternative for Germany (AFD) across the border: first euroskeptical, then nativist, then near-fascist and a party which openly considers the Freedom Party too soft on immigration because it doesn’t want to pay foreign residents in the Netherlands to leave. (The FVD and AFD caucus together in the European Parliament.) The second right-wing party is formally known as the Conservative Liberal Party but everyone calls it JA21, for the letters of the first names of two of the party’s founders, Joost Eerdmans and Annabel Nanninga. It split from the FVD over the FVD’s slow response to an antisemitism scandal. I suppose the JA21’s origin story might put it to the FVD’s left, but practically I don’t think so.

The actual process laid out by the E.U. is that national bureaucrats use the directive’s criteria to draw up lists of sites hosting “wild flora and fauna.” The European Commission then designates “sites of Community importance.” (The directive passed before the European Community renamed itself the European Union.) National governments then have six years to protect the landscape and wildlife in the site.

Technically, the case involved the Nitrates Directive rather than the Habitats Directive.