The American Revolution was good

Without the Revolution, North America looks nothing like the happy Canada we know and love

In 2021, Gabriel Mathy, an excellent economic historian at American University and a friend of mine, wrote a paper arguing that the United States and the world would be better off if the Revolutionary War had never happened.

I think he’s wrong. In the next few posts, I’ll explain why. But here, let me first run down his arguments. I’ll add those of a Vox correspondent, Dylan Matthews, for good measure.

So would skipping the Revolution give us a bigger version of happy Canada … or something worse? Spoiler: something worse.

The counterfactuals

Mathy’s scenario is that the Revolution never occurs, for reasons left unspecified. That then produces a bunch of positive knock-on effects:

No Revolutionary War and no War of 1821, obviously;

More economic integration, a precocious St. Lawrence Seaway, and accelerated industrialization;

Earlier Abolition.

Dylan Matthews in turn gave three reasons why the Revolution was a mistake:

Earlier Abolition;

Better outcomes for American Indians;

A Westminster-style parliamentary system is better than what we have.

Let’s combine into the following:

Greater Canada: more integration, better governance, and faster growth;

Earlier Abolition;

Better outcomes for American Indians.

I’ll ignore the “no wars against Britain” part because, well, yeah. If the colonies refrain from going to war against Britain then there will be no wars against Britain.

Noh Canada

Would North America have industrialized faster and gotten a better constitution without the Revolutionary War?

TLDR: No. There is no plausible world in which the U.S. has better governance (for modern versions of “better”) or industrializes faster without the Revolution.

Why Greater Canada might have been better than the U.S. of A.

Let’s grant for the sake of argument that the Canadian constitution — in terms of its governing structure rather than the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms — is better than the American one. It is certainly better suited to the kind of ideologically-sorted political parties that the U.S. has now.

Paralysis is less likely, because the same party or parties controls the executive and the legislature. That in turn makes it less likely that the executive will aggrandize itself at the expense of the legislature.

Bad or unpopular governments can be easily removed.

Legislative supremacy means no debate about the legitimacy of independent executive bodies, further limiting the power of the executive.

More specifically, in the Canadian case, there is the “notwithstanding clause,” which allows governments to temporarily override parts of the Charter of Rights. That provides a necessary safety-valve and prevents judicial overreach.

But here’s the rub: without the Revolution, you don’t get the current Canadian constitution!

Continental union is unlikely

In fact, if we take Gabe’s counterfactual seriously and postulate that the American Revolution is headed off, then you don’t get any continental union at all. When the Albany Congress was called in 1754 to discuss relations with the Indian nations, it approved Benjamin Franklin’s Albany Plan of Union … but the reaction from colonial governments was resounding disinterest.

For that disinterest to have been maintained, the British would have had to have held off on the acts that increasingly angered the American colonists. That means no Parliamentary overreach. No Revolutionary War means no postwar economic disorder. No Parliamentary overreach and no economic disorder means no pressure for union. A foreign threat might have prompted federation — Canada united in 1867 from fear of the United States — but a timeline where the Revolution is aborted, it is unlikely that there would be any similarly clarifying foreign threat.

Having North America divided into ... uh .... somewhere between 13 and 16 different autonomous entities under the British crown is not a recipe for good government. It is certainly not a recipe for economic integration.

But what if it happened? What would the constitution look like?

Still, it is possible that the colonies might have formed a more unified political space. And that becomes much more likely if the rebels lose the Revolution, rather than if the revolution never happens. Either way, however, the counterfactual would require radically different British policies: the British would have to repeal the entire panoply of acts that increasingly incited colonial ire or give the Americans representation in the imperial Parliament.

Now, let’s just consider what a constitution for a united British North America would look like. We have an example, of course: the Canadian constitution as it stood in 1867. In fact, we have an even earlier example of a union: the United Province of Canada, which federated Upper and Lower Canada in 1840.

The Canadian Senate (and the lower house of the United Province which preceded it) was an undemocratic monstrosity even by the standards of the 19th century. Senators were to be at least thirty years old, citizens by birth or naturalization and hold property of at least $4,000 in the province they represented, appointed by the prime minister for life, with seats apportioned in only the vaguest correlation to population.1

The Senate did what it was designed to do, regularly rejecting major reforms. In 1926, for example, it axed Canada’s first attempt at a social security system. (Footnote #2 goes to a partial list of some major bills amended or rejected by the Senate.2)

The Canadian senate eventually became remarkably deferential to the lower house. (For example, the failed 1926 social security bill sailed through unchanged the next year.) That is in part because the Prime Minister can threaten to appoint more senators and (more recently) because the 1982 constitutional reform removed the Senate’s ability to veto constitutional amendments. But the Senate’s grip held firm for more than sixty years. Only then did its powers begin to erode, and it took until 1982 for them to basically disappear, more than a century after Confederation and 141 years after the United Province first created its upper house.

In the real United States, Southern states were able to block internal improvements thanks to a bundle of constitutional veto points: the preservation of Senate balance between slave and free states, equal Senate representation, and the Electoral College all magnified the South’s power. A British-North-American union would have had to make similarly lopsided concessions to bring slaveholding colonies into the fold, especially if the goal was to bind together regions as politically incompatible as Nova Scotia and South Carolina.

Now imagine designing a constitution for a British North America that includes a bunch of slaveholding provinces. You either get an institution rather like the Canadian senate or you get no unity at all. The southern provinces would insist on equal representation, with an effective collective veto. Quebec, with its own unique institutions, would provide an ironic ally in this pursuit.

Worse, there’s no reason to think such a union would have preserved any kind of majoritarian override. Canada’s own Senate was explicitly designed to check popular demands; if anything, a larger British union with more elite resistance to democracy would have institutionalized even stronger anti-majoritarian safeguards. So instead of creating a governing system that enables reform or integration, you get a structure even more sclerotic than what we got in the real world.

This is not going to result in good governance. In our world, Congress was only able to pass a lot of badly needed legislation when the Southern states gave up their Congressional representation during the Civil War. You got the Homestead Act, the Land-Grant College Act, the Pacific Railroad Acts, the National Banking Acts, and the Second Morrill Tariff Act. None of this is going to come earlier in a world without the American Revolution. It may never come at all, if Mathy is correct and British North America avoids a civil war over slavery.

In short, the absence of the Revolution doesn’t accelerate infrastructure development, even if the continent is united. The reason, simply, is that the politics of union will be the same as in our world through the 1830s, at least: the slave South will be opposed to internal improvements and it will have the power to push through its preferences.

The Canal Guy on the St. Lawrence Seaway

A long time ago, I wrote a book on the Panama Canal. So now I’m the canal guy among economic historians. It’s undeserved. Lots of people work on canals. But it is true that I know a lot about canal-related program activities.3

If I may, here I am going to show a little annoyance with the Mathy paper. He writes:

The Erie Canal was the longest canal in the Western hemisphere. But making short canals through rapids and portages between the Great Lakes and the Saint Lawrence is a much easier task, which was eventually completed as the Saint Lawrence Seaway. This involves making canals in Montreal, along rapids further west in the Saint Lawrence, around Niagara Falls (the Welland Canal), and constructing or widening and deepening waterways between Lakes Erie, Huron, Michigan and Superior. These sections, however, are much easier and cheaper to construct than the Erie Canal, and even provide an easy connection through Lake Champlain and the Hudson River to New York City.

This is wrong. The Erie Canal was finished in 1825 at a cost of $7.1 million, roughly $240 million in today’s money. It had a draft of 4 feet.

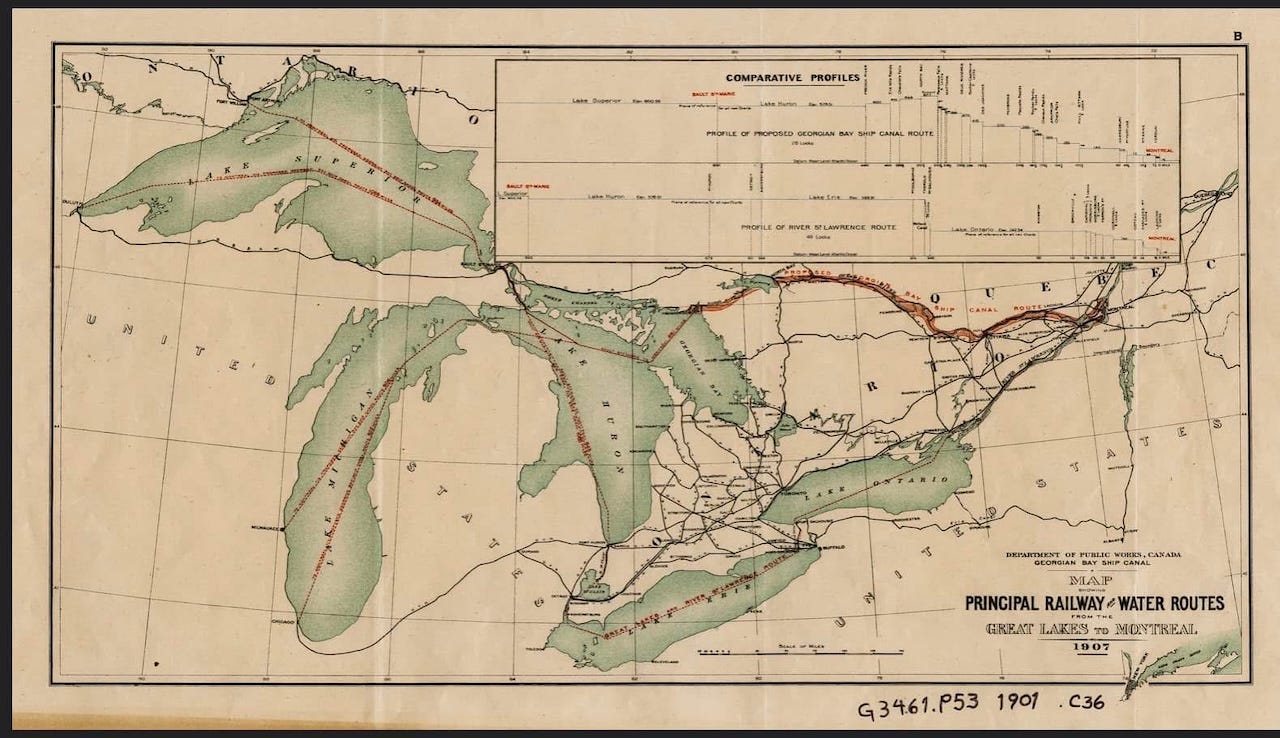

Well, by 1848 an Erie equivalent had been built to Montreal: the Welland Canal (bypassing Niagara Falls), the Williamsburg Canals, the Cornwall Canal, the Beauharnois Canal, and the Lachine Canal (bypassing the rapids around Montreal Island). The St. Lawrence Seaway was a much larger project and far more difficult. It was intended to give sea-going ships access to the Great Lakes. Nothing like it was even considered before the 1850s — and that project took the form of the Georgian Bay Ship Canal project, which was never built even though it was considered easier than what became the St. Lawrence Seaway. (William “Back Roads Bill” Steer has a good recap of the project here; the earlier link goes to the 1908 feasibility study. The 1856 arguments in favor are here.)

So how much did the St. Lawrence Lite cost? Well, there is some debate over the cost of the Welland Canal, with estimates ranging from $2 million to $8 million. Using the low estimate, you get a total cost of $7.4 million for the St. Lawrence Lite, or $310 million in 2024 dollars. That is, I remind the dear reader, almost one-fifth more than the $240 million cost of the Erie Canal.

But, as Fred Scruggs, Tyrone Taylor, and Marlon Fletcher once famously said, “But wait, it gets worse!” Which is that the northern canals regularly froze up in winter. Now, the Erie Canal also froze over, but the freezing was worse and longer up north, as was the cost of maintenance. (The Welland Canal was the big offender here.)

In other words, a precocious St. Lawrence Seaway per se was not going to be built, there would have been no reason to build the actual Erie Canal equivalent any earlier even with North American unity, and there was no way on God’s green Earth that a continental government was going to finance a northern pathway without also financing the New York route. It is just fanciful to imagine Montreal growing larger than NYC or a wholesale reshaping of North American economic geography.

Mathy makes a broader claim that a united Midwest — including modern Ontario — would have prompted noticeably more industrial growth than occurred in our world. This is unfortunately unlikely. Consider:

Mathy asserts:

In this alternate timeline, Southern Ontario would be settled by New Yorkers and New Englanders moving west instead [of Loyalists].

Uh, why? He does not address why we should expect Anglo settlement to dominate, rather than see Québécois migration into southern Ontario, abetted by the British Crown.

Mathy then states:

By unifying the Canadian and American areas of the Great Lakes, this would allow increased industrial growth and a larger economic area concentrating on resource-intensive manufacturing like steel, glass, automobiles, and so on.

There is a debate over whether the Canadian protectionist “National Policy” accelerated the population and manufacturing growth of the region by supercharging Ontarian industry under a tariff blanket. But nobody thinks Canadian independence slowed it down. It’s wishful thinking to believe that free-trade Upper Canada would have sparked scale economies absent in our world.

In other words, Mathy’s premise is wrong. The United States was already large enough to support scale-intensive manufacturing by the 1840s. Adding Upper Canada doesn’t push the country over some threshold — it’s already well over it. Industrial agglomeration in places like Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Chicago happened not because the market was almost big enough, but because it was already plenty big, with internal improvements and unified political support (at least outside the South).

So even if a British North America were more geographically integrated, it’s doubtful it would yield greater industrial scale. Scale economies don’t keep rising with market size forever. At some point — and the antebellum U.S. was already past it — other factors matter more: infrastructure, institutions, investment, and timing. A hypothetical Greater Canada might have been bigger, but it wouldn’t have been better.

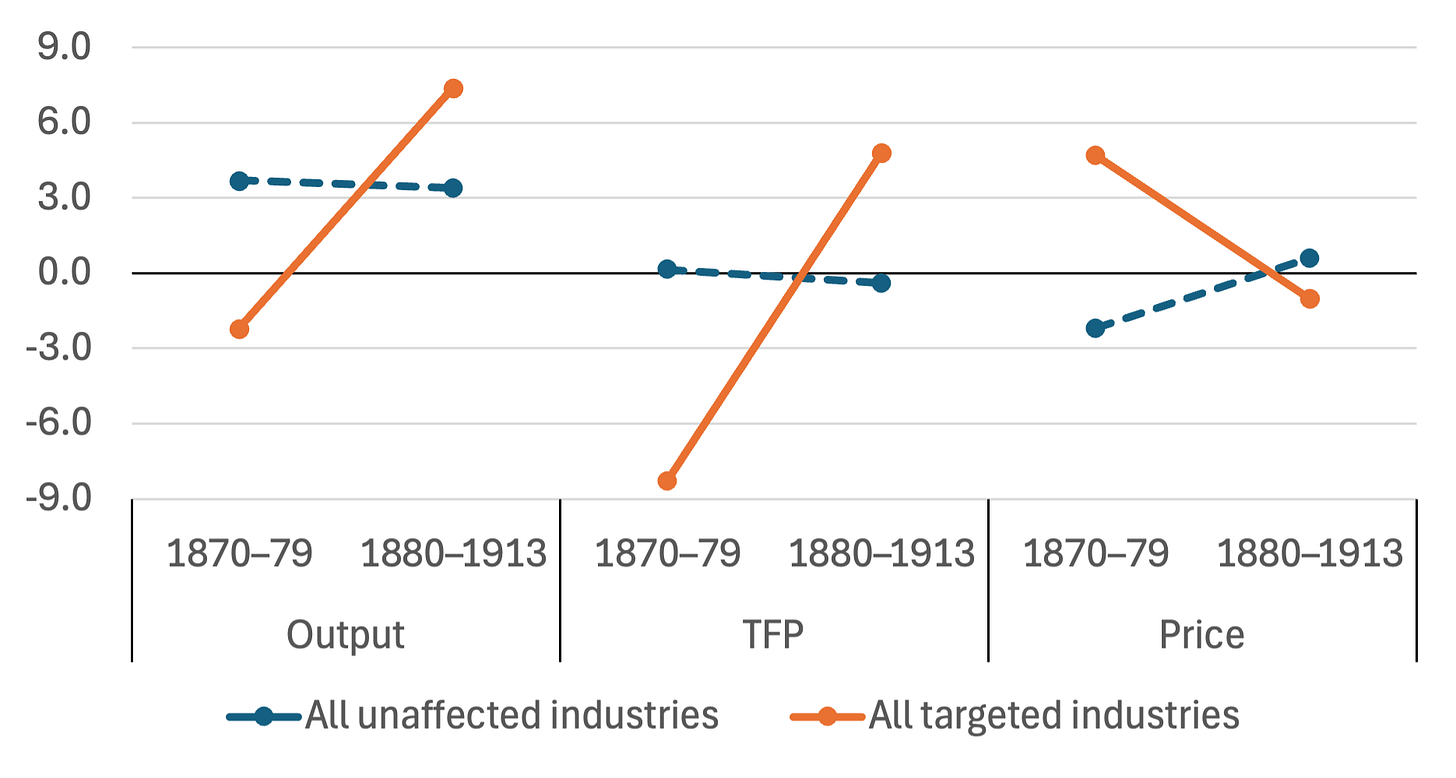

In fact, it might even have been smaller, since Canadian industrial policy likely expanded total North American manufacturing rather than just shifting it away from the U.S. industrial belt. What follows gets us a little past the 1860 cut-off with which I am comfortable, but in 2015 three scholars (Richard Harris, Ian Keay, and Frank Lewis) carried out a worthwhile Canadian initiative and used a differences-in-differences methodology to estimate the success of the Canadian National Policy. They found that firms in targeted industries grew faster, saw more productivity gains, and demonstrated more economies of scale after the policy than they had before.

Of course, the three authors have to deal with the possibility that the Conservative Party authors’ of the National Policy targeted industries that would have grown anyway. They come up with a great strategy to handle that. The Conservative designers of the policy were more likely to protect industries in close ridings than in places where their party had a lock — or conversely, where the opposition dominated. But there is no reason to think that industries in close ridings were somehow “better” than ones in safe seats. So they use close elections to predict for protection, and then they use predicted protection (rather than actual protection) to predict performance. Their results hold!

I conclude that short-circuiting or defeating the American Revolution would not accelerate economic growth or reshape economic geography. In fact, it might have even retarded North American manufacturing growth. But I call upon Vincent Geloso to confirm or deny! Vincent, for those of you who don’t know, has worked a lot on Canadian economic growth and written a bit about the economic impact of the American Revolution.

Too long, didn’t read

If there is no Revolution, then North America probably does not unite and winds up poorer than in our world. If it does unite — maybe because the Americans are defeated instead of pre-empted — then its government does not look at all like our happy shiny Canada. Rather it’s a looking-glass more-reactionary version of our antebellum United States, dominated by slave provinces in a perverse alliance with Quebec to defend their “peculiar institutions.” Any federal infrastructure development is therefore significantly slowed.

In the words of my father, “At best, this ends neutrally.”

Next up: slavery and the American Revolution.

Technically, the Governor-General appointed them on the advice of the Prime Minister.

Here is an abridged ten-item list of Senate vetoes:

In 1875, the upper chamber rejected a bill for the construction of a railway from Esquimalt to Nanaimo in British Columbia on the ground it was an unwarranted public expenditure.

In 1879, the Senate turned down a bill to provide for two additional judges in British Columbia on the ground that the provincial government was in the midst of an election and had, under the circumstances, no right to ask for the increase.

In 1899 and 1900, the Senate rejected a bill to re-adjust representation in Ontario on the alleged ground that it was inexpedient to proceed with the bill until after the 1901 census.

In 1909, the Senate rejected a bill allowing appeals in claims from the Exchequer Court to provincial Supreme Courts in certain cases on the ground that it would lead to unnecessary litigation and confusion.

In 1913, the Senate defeated the Naval Assistance Bill.

In 1919, the Senate threw out a bill bringing the Biological Board of Canada under the jurisdiction of the Minister of Marine and Fisheries on the grounds that the Board should be independent and protected from political interference.

In 1924, the Senate rejected seven bills and drastically amended three others authorizing the construction of branch lines for the Canadian National Railway.

In 1926, the Senate rejected the Old Age Pension Bill on the bases that: (1) there was no general public demand; (2) the provinces had not indicated approval, and (3) public pensions were socially undesirable.

From 1930 to 1940, thirteen bills failed to pass the Senate, including one private bill relating to patents, a bill relating to pensions for judges, and a bill extending the Farmers’ Creditors Arrangement Act.

In 1961, the Senate insisted on amending the Customs Act.

And it is a sign of my age that I still find that phraseology funny.