Nearshoring in Mexico has been a failure but it’s not all AMLO’s fault

A missed opportunity that may go on missing

In 2022, I was invited to Querétaro to talk about nearshoring. I think I disappointed everyone, because I said that despite the hype, it really hadn’t amounted to much yet.1

My main evidence was that Mexican manufactured exports to the U.S. had simply returned to their pre-covid trend. They were neither exceeding the pre-2020 trend nor gaining market share from the rest of the world:

We’re now two years on and unfortunately mass nearshoring to Mexico still refuses to materialize. The country’s share of U.S. imports has crept up a little, but a giant boom this is not. (I realize that the title of the below chart draws the opposite inference; I do not think that is warranted by the evidence.)

Why not?

(1) USMCA rules make it hard

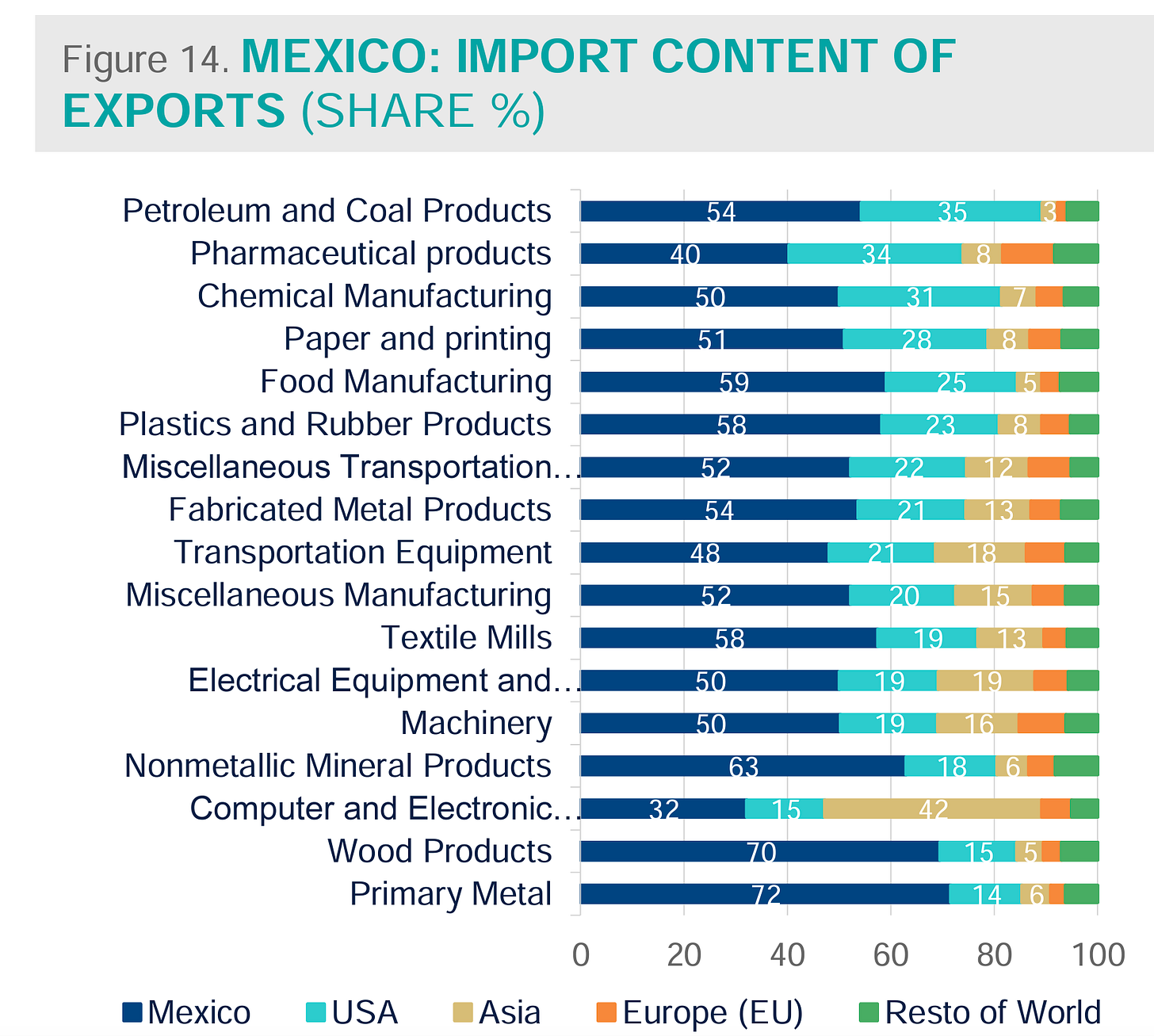

Under the USMCA, exports to the U.S. need at least 60% of the value-added to happen in North America to get preferences.2 That means you can’t just export parts to Mexico and slap them together, not unless you want a costly audit.

Look at the line labeled “computer and electronic.” Right now, most Mexican exports in that category are not eligible for USMCA preferences. That is one of the most promising categories for nearshoring, but getting it under the U.S. tariff wall will require recreating large chunks of the value chain inside North America. Places other than Mexico are better positioned to do that.

(2) Capacity contraints

In 2008, my co-authors and I pointed out that one of the reasons NAFTA hadn’t supercharged the Mexican economy was that many of the inputs for export industries come from the non-traded sector, and that sector was inefficient and starved for capital.3

That problem still exists today. Consider one of the most important non-traded input: factory space. The annual net increase in industrial real estate has grown from 2.0 million square meters in 2019 to 5.0 million square meters in 2023. At the same time, the vacancy rate has plummeted from 5.5% to 2.2%.4 That’s a sign that the construction business is laboring to open the amount of new industrial space that investors need.

So despite an incredible construction boom (see the below figure from S&P Global), Mexico just can’t build enough space even for its current modest growth. Sustaining a 20% growth rate is not going to be easy.5

Add to this constraints in electric power, transportation, and labor. Considering power, the Mexican Association of Private Industrial Parks (AMPIP) found that 91 percent of Mexico’s facilities faced energy supply problems in 2023.6 With industrial energy use rising fast, this is a major constraint.

As for transportation, Mexico ranks the worst in the OECD according to the World Bank. Skilled labor has always been a problem, but AMLO’s reforms have increased unskilled labor costs substantially. (Although to be honest, I think that is a cost well worth paying — unlike the other problems, the recent increase in labor costs did in fact come with some pretty substantial benefits for the median Mexican worker.)

Now add in the fact that the increase in public sector construction hasn’t been concentrated in things that the export sector needs (with the possible exception of the Tren Interoceánico) but in more idiosyncratic projects like the Tren Maya and the Dos Bocas refinery.

You want a sustained manufacturing boom in a trillion-dollar economy? You gotta not just spend the money, you gotta develop the capacity to spend the money, and that takes time.

(3) New investors are running scared

There has been a lot attention paid to some major greenfield announcements in Mexico. Tesla’s gigafactory in Nuevo León would be Exhibit A — although let’s not forget that Elon Musk froze that investment in June pending the U.S. election.7

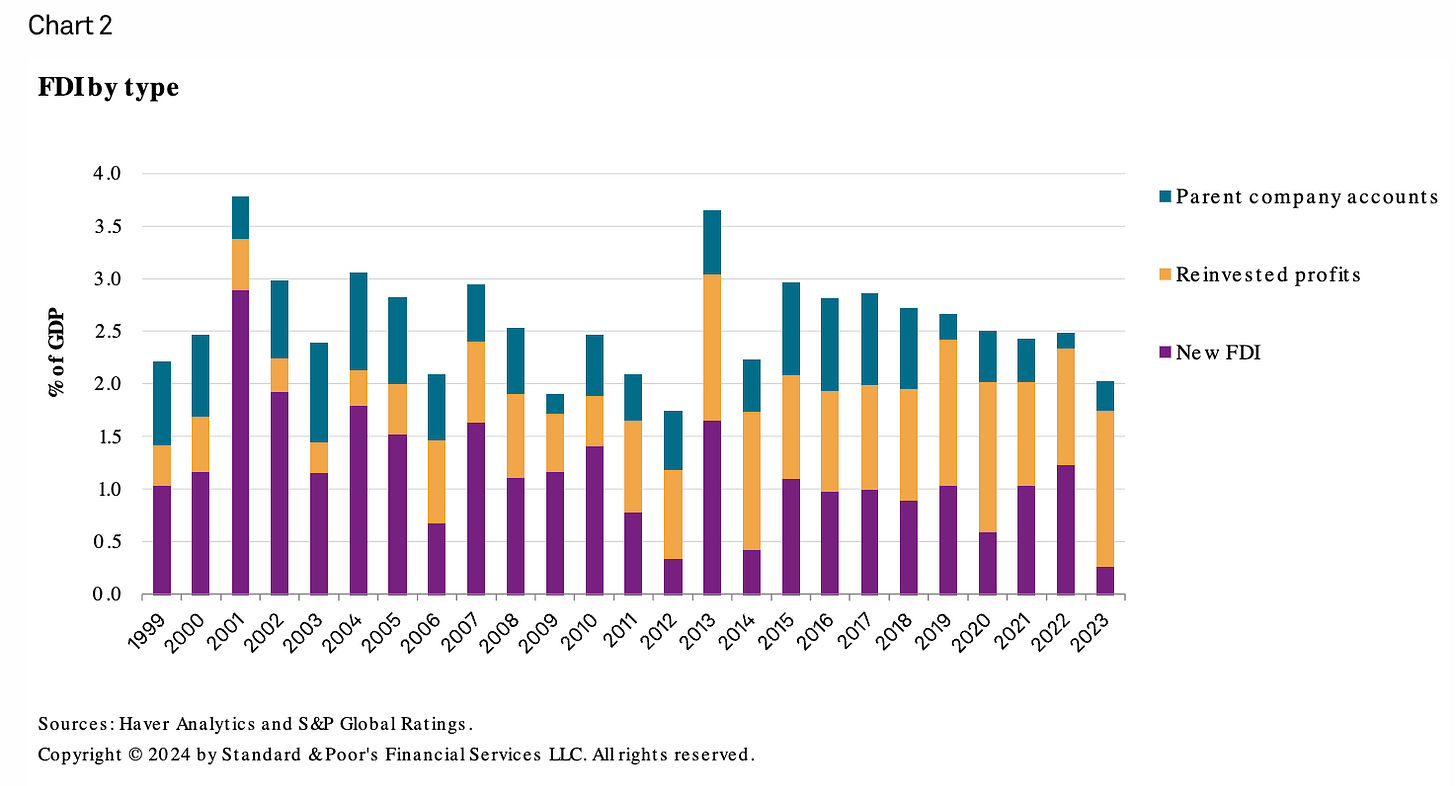

Eduardo Saucedo of the EGADE business school in Monterrey took a closer look at the numbers. And what did he find? Most new foreign investments in Mexico have been financed out of the retained earnings of existing Mexican operations. There are remarkably few expansions of existing operations financed by outside capital, let alone greenfield investments.

This fits the data from S&P Global:

In other words, foreigners seem to be willing to expand their existing operations in Mexico using resources generated in Mexico. Risking outside capital, not so much. And that’s a problem, because according to a 2022 survey by Mexico’s central bank, three-quarters of Mexican exporters aren’t in product lines that their managers think have benefited from nearshoring:

What could go right?

Well, the peso is falling, so there’s that.

The dotted line was the election. So I can’t say that the reasons for the peso’s fall were salubrious, but markets (like everything else) can do the right thing for the wrong reason.

Otherwise? Sure, the Mexican government’s gotta fix the energy problem. Mexican businesses need to up their game, not least when it comes to productivity. And everyone needs to provide more certainty — both in Mexico City and in Washington. None of that is impossible.

But nearshoring was never going to be easy. And there was never a guarantee that Mexico would be the chief beneficiary, despite its obvious advantages. I hope the boom materializes over the next three years. But despite all the post-covid hype, it hasn’t yet, and the obstacles are real.

My stance was, in part, based on the experience of a former student, who’s company had gotten business by taking Chinese goods and adding just enough value to get out from under the high tariffs on Chinese products. see footnote (2). It may surprise you to know that U.S. rules only require the product to be “substantially transformed” in order to avoid country-specific tariffs—if that sounds vague to you, that’s because it is. Now, if you want to bring it in under preferences laid out in the agreement formerly known as NAFTA, it’s a bit harder: you need to have 60% local value-added. But you can engineer that as well: the Chinese supplier will likely take a loss by selling the inputs cheap to their Mexican colleague, but as long as its less of a loss than the U.S. tariff then it will work for them.

I really miss NAFTA as an acronym, but that’s a battle that I can’t win.

Here is a quote from p. 94 of our book that explains the problem:

Consider, for example, an automobile manufacturing plant financed with FDI. Its output of automobiles is tradable, and it consumes many tradable goods such as tires, windshields, brake linings, and cylinder heads. Yet it also consumes a wide variety of nontradable items, such as the construction of buildings, machinery repair and maintenance, and accounting and legal services. The workers in this automobile plant also consume a great variety of nontradable goods (for example, haircuts, restaurant meals, public transportation, and home construction and repair), and they must price their labor in accordance with the prices they pay in the nontradable sector. Thus, the firm’s labor costs, as well as the cost of many of its production inputs, are determined by the productivity of the nontradable sector. If the growth of productivity in the nontradable sector is slow, then firms in the tradable sector will face higher prices than they would otherwise. These higher prices will, in turn, influence the prices that firms in the tradable sector must charge for their output. In short, the long-run performance of the economy hinges on the performance of myriad economic activities whose sources of finance are domestic.

Source: AMPIP, “El sector inmobiliario industrial en México,” https://www.ampip.org.mx/sector-inmobiliario-industrial.

This is going to be doubly true going forward, because some of 2023’s supergrowth involved pulling back into operation some excess construction capacity that had left unemployed by the 2020 covid shock. That’s all done now — construction firms will need to train new workers and buy new equipment going forward.

Source: AMPIP, “Los parques industriales como instrumento de desarrollo nacional: Retos en Materia Energética,” (October 2023).

People often do things because they believe in them. If you read the article, then you would surmise that Musk’s businesses would do better if Harris wins the election, and you would probably be correct.