Los primeros cien días

The Milei Administration 100 days in

The first 100 days is iconic in American politics. When FDR assumed office at the nadir of the Great Depression, he got Congress to pass 15 major laws, laying the foundation for the New Deal. Barack Obama took office during the Great Recession and his first 100 days received its own Wikipedia page. He wasn’t quite as productive as FDR. The Recovery Act was the only bit of Obama’s agenda to pass in the first 100 days; the Wall Street Reform Act and Affordable Care Act had to wait until 2010. Joe Biden, meanwhile, managed to get the American Rescue Plan through Congress and took a host of executive actions in his first 100 days, but the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act didn’t pass until Day 300.

What about Javier Milei?

Milei did one very large and sadly necessary thing which caused or enabled everything else. But other than that one very necessary thing—which so far has made life worse for most Argentines—the cupboard is bare, compared to the rhetoric.

Legislative accomplishments

Nothing. Nada. Bupkis.

Here you can find data on all the votes in the lower house of Congress. Senate votes can be found here. The Chamber of Deputies has taken some votes to amend laws protecting women from digital harassment and children from real life abuse, approve a vacuous national technology plan proposed by the previous administration, and reject piecemeal the giant “Omnibus Act” that President Milei sent to the legislature.1

The Senate, meanwhile, did even less. It approved some minor tax and investment pacts with the UAE, the PRC, and Türkiye. It voted on an amendment to the money-laundering laws. And on March 14th it voted 42-25 (with five abstentions) to overturn the “Decree of Necessity and Urgency” (DNU) that President Milei proclaimed soon after taking office.

The latter vote was a complete screw-up. Milei’s veep, Victoria Villarruel, could have kept the bill from reaching the floor. She claims that two Peronist breakaways from the Fatherland Union told her that she should put the bill on the agenda because they might be able get the two-thirds needed to bring the bill to the floor over her opposition.2 (With friends like those, who needs enemies?) To be fair, the whole story turns on points of Senate parliamentary procedure that we have not been able to fully decipher—but on page 32 it sure looks like the Vice-President (in her role as President of the Senate) has the authority to decide what is and what is not going to be voted upon.

Strong-arming Congress won’t require President Milei to moderate his public image (although that would help!) but he will need to get much better at pulling the lever.

If you needed any evidence that Milei is not yet a new Ronald Reagan, let alone FDR, you got it here. Hmm. “What if Lyndon Baines Johnson had been Argentinian?”3 LBJ would have a field day using the powers of Argentine president to get what he wants from Congress. Milei, so far, could be using those powers much more effectively than he is.

Executive actions

What about the aforementioned DNU? The courts struck down the provisions dealing with labor unions, but the rest is still in effect. (Unless the Milei Administration turns out to be as hapless with the lower house as it was with the Senate.) And the Administration is appealing the decision on the labor union clauses.

But love it or hate it, the DNU is a long-term measure. It’s about deregulation and privatization, not stabilization or recovery. Now, some of its measures could be felt as soon as recovery hits. The removal of rent and price controls might be destabilizing—but our direct experience with the rental market in suburban Buenos Aires leads us to think that the former will have only a positive effect, bringing more units into the market.

One problem, however, is that President Milei filled it up with controversial and ideological positions that serve only to catalyze opposition.4

If Milei manages to keep the lower house from repealing it, then the reforms may pay dividends in years to come. But Argentina needs to recover now, not years from now.

The Motosierra

That famed chainsaw Milei intended to take to the federal government? In terms of employment, the sawchain is still off the bar, just like it was in his rallies.

President Milei took office on December 10. As of January 31st, the last date for which we have figures, the federal payroll was 2,389 higher than it had been at the end of November. “Administración centralizada” refers to all agencies that “depend on the national executive in order to administer and use their resources.” So that’s where he could make the biggest cuts … and apparently did not.5

He cut the number of ministries in half, from 18 to nine, but that’s a very different thing from saying that he eliminated the federal programs that those ministries had been carrying out. Same thing regarding the audits of government contracts for fraud—even if fraud were found, the President can’t simply impound the money and not spend it.

Spending cuts

The Milei administration has severely cut spending, even if headcounts haven’t really fallen. They have even pulled out a primary budget surplus. How did they do that? Three ways: cut pensions (35% of deficit reduction), cut energy and business subsidies (12%), and cut capital spending (24%). Let’s take them in turn.

Pensions

Milei had the ability to cut real pensions because the outgoing Fernández administration gave it to him.

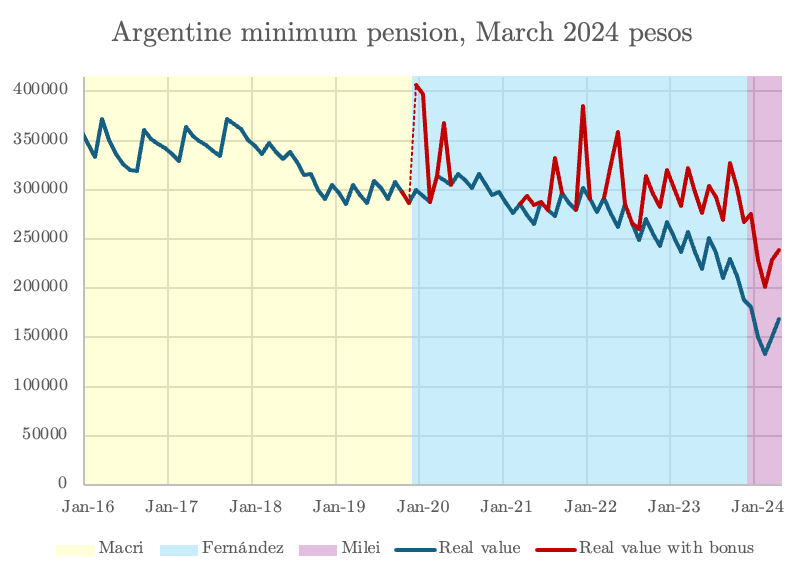

First, base pensions in Argentina are indexed to inflation, but with a three-month lag. So when inflation accelerated at the beginning of Milei’s term, base pensions fell. That’s the blue line in the below chart.

Now, Milei could have issued additional bonuses to pensioners—the red line includes bonuses. And he did issue bonuses—in fact, as a share of the basic pension, his bonuses have hit an all-time high of 52%. But as you can see, he did not raises bonuses by nearly enough to make up for the inflation-induced fall.

Why were pensions topped-up with discretionary bonuses at all? Well, the Fernández administration wanted everyone to know that they were saving people’s retirement payments. So instead of rejiggering the inflation formula, they issued a DNU that gave them the power to grant bonus payments at will.6 Of course, that meant that President Milei had the power to issue smaller bonuses that didn’t make up for inflation.

The plan now is to hike pensions by 12.5% and then link them to monthly inflation. In other words, the administration plans to make the cuts permanent.

Subsidies and capital spending

In early 2024, energy subsidies made up about 6% of spending. Milei has cut them in half. But as of now, those cuts are just delays in paying Cammesa, the distribution company. It’s blowing holes in the generators’ cash flow. The plan is to have prices rise enough to end the need for subsidies next month, but the government is almost certainly going to have to shell something out to make up for the last two months.

A similar problem exists for the suspension of federal transfers to provincial governments.

Milei has cut some support for state-owned companies, but the chainsaw really hasn’t gone brrrrr yet, regardless of the impression you might get from this Financial Times article. Privatization, meanwhile, is stuck in Congress.

Capital spending is down more than 80%, which has wrecked the construction industry. The problem there is similar to the one above: it’s an emergency measure. In a country like Argentina, infrastructure spending will certainly have to rise above the pre-Milei status quo; it is a terrible place to make permanent cuts.

TLDR: big drops in cash flow from the feds. But the real action is to come, when the administration raises real energy prices and (somehow?) makes the cuts in provincial transfers permanent. So you can’t really credit this as a “first 100 days” accomplishment.

The Big Reform

Devaluing the official exchange rate for the peso. That needed to be done, but it generated a massive burst of inflation. As Nicolas Saldías pointed out, everything so far has been downstream of that—the spending cuts, the rise in poverty.

But generating more inflation when you were elected to control inflation is a pretty ironic main accomplishment for the first 100 days.

And we hate to point this out, but Argentina still has multiple exchange rates and restrictive capital controls.

Inflation is now coming down, but without that big unanticipated jump in the price in December and January, none of his other accomplishments would have happened.

Summation

What have we got?

Legislation: nothing.

Executive action: deregulation, but the Senate has already voted to repeal.

Restructuring the state—personnel: so far, nothing.

Restructuring the state—spending cuts: other than pensions, it’s not clear that they can be sustained for more than a few months. Pension cuts were enabled by the previous administration’s machinations combined with the burst of inflation.

Restructuring the state—state-owned companies: nothing substantial.

Subsidies—see (4) above. The real action is up ahead.

Macroeconomics—inflation in February ran at an annualized rate of 343%. No sign yet of Morning in Argentina.

The hundred-day standard is unfair. FDR came to office in a pretty unique set of circumstances. It would be hard to repeat that record. Milei did not repeat it.

He needs to be a better politician and he needs more economic strategy. As in, a sequenced plan of action that takes into account the fact that other political and economic actors will respond.

For not a lot of governmental action, there has been a lot of public passion. But that’s something for another post.

Hopefully the next 100 days will show more movement than the first.

You may have read that the Chamber approved the law on February 6th. That isn’t correct. First, the Chamber leadership stripped out all the tax hikes before breaking up the bill and sending it to the floor in pieces. The Chamber voted in favor of Article 1, which stated the general aims, but then proceeded to reject clauses about the energy sector, law enforcement, bureaucratic reorganization, privatization, and the management of state enterprises. At that point Milei gracelessly gave up and the Chamber leadership sent the whole thing back to committee. You can get a good sense of the individual votes at this webpage, but go quickly—that link will rot.

The rogue Peronist senators are Carlos Espínola and Edgardo Kueider.

It’s an economic history joke that is only funny to fans of Dick Sylla. We are a huge fans of Dick Sylla.

One idiotic misstep: the law allows Argentine football clubs to convert themselves into fully private organizations, a la American sports teams. Argentine football clubs are pillars of their communities. We love the Yankees, but as the famous line goes, “Joe DiMaggio doesn’t pay your rent.” In Argentina, however, clubs “provide facilities for dozens of other sports, education and healthcare services, and even run the odd university.” (River Plate runs a university.) This fact means that fans have reasons to object beyond their fandom. It also means that the courts have reasons to get involved, since the decree effects more than just the clubs and their paying customers.

An anecdote: When Noel lived in Mexico, his downstairs neighbor was an Argentine named Fabio. This was during the late 1990s, when the Yankees dominated baseball, as God intended. (Except ‘97. Damn you, 1997.) In 2000, Fabio discovered the existence of another New York team in the National League and the fact that Noel strongly preferred their rival in Los Angeles. That led to a recount of the whole story about why they moved across country.

Fabio’s reaction? “What? That makes no sense. It’s as if, well, uh …” He tried to verbalize the thought and failed. “Boca wasn’t Boca. It’s…” A pause. “Uh, it’s Boca! How could Boca not be Boca?”

This gives an idea of just how alien the American (or European, really) concept of corporate sports teams is for Argentines.

“Administración descentralizada” refers to agencies whose budget is set by Congress and which possess a degree of independence from the federal executive. Milei can still fire people in these agencies; what he can’t do is refuse to spend money that Congress has already authorized for them. “Administración desconcentrada” consists of civilian employees of the armed forces, the statistical agency, the Foreign Trade Commission, and the Office of the Attorney General of the Treasury.

The December drop in central office personnel was due to the transition; many positions were still vacant at the end of the month.

The Pension Adjustment Act of 2008 updated pensions for inflation twice a year, in March and September based on a formula that combined a wage index with social security revenue revenue. In December 2017, President Macri pushed through the Pension Adjustment Index Act, which increased the adjustments to quarterly and replaced the previous index with one based 70% on the CPI and 30% on the nominal wage index. But the adjustment used lagged inflation from six months previous … for example, for the June adjustment, it used the inflation rate between September and December the year before. President Fernández, he issued a DNU in December 2019 to allow him to grant discretionary quarterly increases above the Macri index. In March 2021 he got Congress to pass a law revising the index again, to be 50% the increase in social security revenue and 50% the increase in the nominal wage index. Inflation was still lagged by three months, so the June adjustment would use the inflation rate between January and March.