It’s not the economy, stupid

But then what are Panamanians so angry about?

Panamanians are angry. The country has recently seen mass protests that blocked streets and shut down traffic in Panama City and several large towns. There has also been a wave of strikes. Hotels have been hit; Chiquita estimates that it’s lost about $10 million worth of bananas so far. Public construction is paralyzed.

It would be natural to look for economic roots for the discontent. But the more you look, the less the economy seems to explain it. The real problem may be how the political system handles public anger rather than the ire itself.

A poturri of pressures

As the esteemed James Bosworth pointed out, “Negotiating with protesters is tough when they don’t know what they want as a group.” Students seem angry about the basing agreement with the United States. The powerful Suntracs construction union is angry over a slew of different labor disputes. The various groups that demonstrated in ‘23 are angry over proposals to reopen the Cobre Panamá copper mine. All of the above are angry about the way the United States has pushed around its most loyal Latin American ally.

And nobody likes the upcoming Social Security tax hike.1

The atmosphere feels febrile. In 2023, massive protests erupted around the Cobre Panamá mine. But as Bosworth also pointed out, the anger remained even after Panama’s supreme court shut down the operation. The next year, in 2024, the electorate crushed the incumbent Democratic Revolutionary Party. They would have handed the reins back to former president Ricardo Martinelli, but the Supreme Court declared Martinelli ineligible to run due to a corruption conviction. So José Mulino ran in Martinelli’s place and won.2

The electorate seems to hate almost everybody — former president Martinelli is the only major politician with an above-water approval rating. And he just left for Colombia after spending a year holed up in the Nicaraguan embassy in order to avoid prison time for a money-laundering conviction.

Given all the apparent anger, it would be odd not to expect to find something wrong with the Panamanian economy.

Only there’s not.

Follow the money

Over the past quarter-century, Panama has been experiencing a phenomenal economic boom. Here are the standard figures of GDP per capita, where you can see Panama blowing through the rest of Latin America, including former star performer Chile:

There was an economic slowdown in 2024, but that was caused by the closure of the giant Cobre Panamá mine — in other words, the deceleration was more the result of political unrest than the cause of it. Open unemployment ticked up from 5.8% in 2023 to 7.8% in October 2024 after years of steady post-Covid declines, but that doesn’t seem to have fed the protests — overall employment held steady and outright recession has thus far been avoided. If the protestors are demanding jobs or handouts then I haven’t heard of it.

Still, I have seen many economic booms that raised GDP per capita but did not result in broad-based income gains. I’m looking at you, Dominican Republic. Falling or stagnant wages would certainly fuel discontent, even if GDP is growing. So let’s rewind to 2008, when real wages in Panama were basically flat, and track what changed.

Panama, fortunately, has very good data collected from a thorough annual labor market survey. That lets us follow average and median wages, the best indicator of overall living standards. And that data show, in 2024 dollars …

… pretty astonishing gains, after decades of stagnation. Adjusted for inflation, average wages have climbed 58% since the Great Recession of 2008. Median wages rose almost as fast, rising 51%. That’s astounding by any standard. Wage growth has been rockier since Covid, but that’s true everywhere.

In rough terms, Panama boomed from 2007 to 2019, got clobbered by Covid, recovered strongly in 2021–23, and ran straight into political turbulence in 2024. You would have to read a lot into the last few years of flat median wages to draw a direct line from that to political unrest.

Follow the recipients of the money

But wait, you say, inequality may have increased! After all, average wages rose faster than the median, implying large gains at the top. And overall GDP rose much faster than wages, which could mean large increases in capital income. Perhaps Panamanians are angry about that!

Panama runs very comprehensive labor market surveys, which also track income from transfers. It uses that data to calculate income inequality, which we normally measure using something called the Gini coefficient. At zero, everyone in your country has the same income. At one, a single household is collecting all the income and everyone else is about to die of starvation. The U.S. is currently at 0.41; at our most equal, in 1980, we measured 0.35.

And that data show a pretty large fall in inequality in Panama:

In other words, Panamanian inequality is still very high, but it’s falling pretty bloody fast.

How does falling inequality jibe with the other data I showed? Two facts explain the mechanics. First, incomes at the very bottom rose faster than they did at the median, as the demand for unskilled labor outstripped the supply.3 Second, Panamanian businesses plowed rising shares of their profits into fixed investment, rather than redistributing them to their owners. Investment in fixed capital as a share of GDP rose sharply from 28% in 2007 to hover around 40% in 2014-19, before dropping when Covid hit.4 Put another way, the Panamanian savings rate increased from around 20%-21% before 2007 to 36% today.5

If you don’t trust economic indicators, then life expectancy is a blunter measure of overall national well-being that will not rise much unless gains are broad-based. As P.J. O’Rourke once pointed out, you can’t (yet) increase average life expectancy by letting a few really wealthy people live to 1,000. Panama shows downward blips around the 1989 invasion and the Covid pandemic, with the former likely caused by crushing pre-war sanctions rather than military action. Otherwise life expectancy has serenely marched upward since 1960, and even accelerated at the tail end of the 1990s.

Follow the value of the money

Jumping back to the present, if it’s not economic growth and its not inequality, so maybe it’s inflation? If Panama is experiencing inflation, then people will be unhappy, even if they have enjoyed real income gains. The psychological explanation for this is simple. If your salary goes up, you attribute that to your hard work. But when prices go up, that’s somebody else taking the fruits of your labor away from you. Very few people think, “Oh, I got an 8% raise last year, but inflation was 5%, so if prices hadn’t gone up then I would have only received 3%, it’s all fine.” Even writing the sentence seems convoluted.

Once again, let’s go to the data. What do we find?

Inflation in Panama has generally been much more subdued than in the United States. The inflationary blowout that hammered Americans in 2021-23 was barely a blip in Panama. Now, Panama did experience an inflationary blowout in 2005-15. But that was the kind of inflation you get when demand outpaces supply due to an economic boom. Wages rose and so did spending. It would have been more surprising if prices hadn’t jumped.6 And while that inflationary episode produced a lot of discontent at the time, it’s hard to imagine that people are still be angry about it a decade later.

Are there violent attempts to steal the money?

Maybe the issue is security. If the streets aren’t safe, no one will be thinking about GDP per capita. What’s the use of a rising paycheck if some mugger might take it away from you?

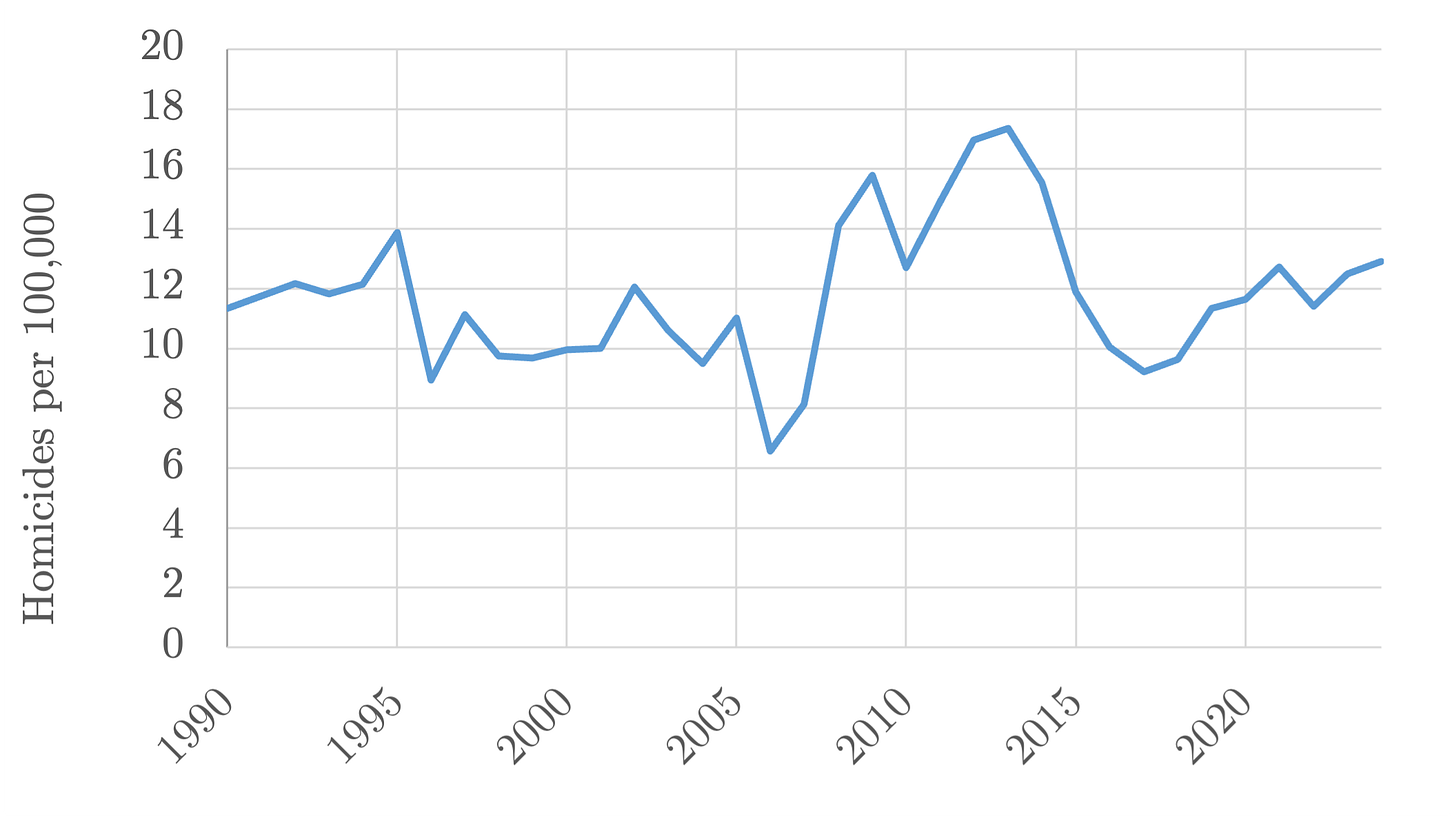

In terms of homicide, there’s not a lot to see. There was an upsurge of violence during the economic boom, but the murder rate dropped significantly in the mid-2010s and is now more or less back to its (high) historic norm:

And this jibes with what Panamanians say when asked what has the biggest impact on their quality of life. In a survey undertaken in January and February of 2024, crime barely got a mention compared to health, family and friends, and the cost of living:

Polls show overwhelming numbers of Panamanians think that crime is far too high, and self-reported victimization rates have risen. The same poll cited above also showed that roughly 22% of households reported having a member victimized by crime in the past year. That’s up from 17% in 2010, but less than the 2017 peak around 24%. You have to squint really hard to see a pattern in the annual variation. And crime seems to be one of the few things that does not preoccupy the protestors.

Protests and politics

The protests are all over the map in terms of what they want. Maybe it’s the social security tax hike.7 Maybe it is the copper mine. Maybe its the military bases. Maybe it’s watching the Trump administration walk all over the Mulino administration. And corruption really is bad — I did mention that the popular former President just accepted asylum in Colombia in order to avoid jail time? Eventually frogs really do jump out of boiling water. Perhaps Panamanians are just waking up to their political dysfunction? Somehow that feels improbable; the Panamanian electorate was pretty sophisticated in the 1990s and 2000s and the country’s corruption wasn’t exactly a state secret.

And at the end of the day the economy is in fine fettle. The current slowdown is entirely self-inflicted — from the shut down of the Cobre Panamá project — and even if it weren’t, I don’t know of anywhere on Earth where a couple of years of mild wage stagnation would produce this level of anger, especially coming on top of the very large gains in recent years. If we dig down, there are some blinking yellow lights, but that’s true in most national economies.

There is one last hypothesis, which is even less satisfying, but may be true. Panama is a Latin American country, and Latin Americans demonstrate. They march in Mexico City, they boycott in Buenos Aires, they assemble in Asunción.

Maybe it’s not the demonstrations that are unusual, but the ability of the demonstrators to get what they claimed they want. Last year they shut down a copper mine that employed 2% of the workforce (40,800 people), paid 3% of the tax revenue ($480 million), and generated 5% of the GDP. This is a “success” that most Latin American protest movements can only dream about.

But an own-goal of that magnitude is understandably a little frightening to investors. Maybe it’s not Panamanians who are particularly angry, but Panamanian politicians who are particularly inept.

In 2023, the politicians couldn’t hold the line. First, they negotiated a mining contract in a gratuitously shady manner. Then, unlike their Chilean counterparts, who faced a much bigger social eruption in 2021, they failed to channel the discontent into political action. Instead, under cover of the Supreme Court, they punched their own national economy in the face.

Perhaps what looks like public rage is simply what happens when public pressure actually works. If you can shut down a mine with a few marches, why not try it again? A political system that pinballs in the face of protest may be more unsettling than the protests themselves.

Panama currently collects a 22% payroll tax to fund social security. On paper, employers pay 12.25% and employees pay 9.75%, although anyone who has run a payroll will tell you that they think of it as a combined tax. The employer portion is now scheduled to rise by one percentage point immediately. In February 2027 it will rise a second point, and then a third point in February 2029, to a total rate of 15.25%. Independent professionals — which in practice means a lot of small businesspeople and general contractors — will also become subject to social security taxes for the first time, at a rate of 9.36% on their earnings.

President Mulino’s party is known as RM, short for “Realizando Metas.” A friend of mine likes to joke that RM really stands for “Reeliga a Martinelli.”

There was also a modest increase in government transfers, but this was small, since the Panamanian government collects relatively little revenue to redistribute.

It fell to 24% and recovered to 32% as of 2023.

National savings peaked at 37% right before Covid, fell to 28% during the pandemic, and are now back to 36%. Savings rates are calculated from the components of nominal GDP published at the Mapa de Información Económica de la República de Panamá. The U.S. savings rate is roughly 18%, measured this way; China is around 44%. So one way of thinking about the change is that the Panamanian economy has gone from looking a lot like the United States in 2000 to looking a lot more like China’s in 2025.

Unlike China, however, there is no policy shift that you can point to in order to explain rising national savings. Panama doesn’t force its companies to bank their export earnings. Nor does it deliberately repress wages, discourage dividend payments, ban unions, or run big budget surpluses. My hypotheses is that rising savings are a lagging indicator: the economy took off, generating a lot of profit opportunities, and Panamanian companies and households decided to save more in order to take advantage of those opportunities.

The basic formula to calculate national savings is:

national savings = domestic investment spending + net foreign investment

In turn, net foreign investment is equal to the current account deficit —> if a country sells more to the rest of the world than it bought from it, then it has to park the excess in foreign assets, the same way that an individual who spends less than she earns parks the savings in an external bank account or some other investment asset. (Even if you stash cash under a mattress, that’s technically a liability of the Federal Reserve, and thus a “foreign” asset from the point of view of an individual.) Conversely, if a country buys more from the rest of the world than it sells, then it needs to borrow from abroad, finagle foreign equity investment, or sell assets to cover the gap.

Digression: Panama’s inflation, 2005-15

The reason for the inflation surge during that decade isn’t complex: it’s what happens when you have a local economic boom in a fully dollarized economy. The demand for labor soared. Wages then rose. So did the demand for haircuts, dry cleaning, movie tickets, taxi rides, electric power, and much else. The prices for that stuff shot up until domestic supply was able to rise sufficiently to meet the increased demand. That is normal; it would happen in any part of the United States that experienced a sudden boom. Go look at prices in West Texas or North Dakota when fracking took off, or ask why California is so damn pricey!

What worsened inflation in Panama is that the country’s agricultural policy is highly protectionist, sometimes under the guise of health and safety concerns. For example, in 2016 the Panamanian Food Safety Authority unilaterally withdrew import permits from Brazilian meatpackers in order to protect Panamanian hamburger-makers. Rice is even more protected. The upshot was that when demand spiked during the boom, imports couldn’t increase commensurately.

The result was price hikes followed by price controls followed by a jump in direct fiscal support to agriculture from around $18 million in 2010 to $167 million by 2019. (See Egas et. al., “Análisis de políticas agropecuarias en Panamá,” Informes de política agropecuaria (BID: 2023), particularly Table 3.) And those figures understate fiscal support, because the sugar and banana industries were still net generators of public revenue that went to support rice growing and cattle ranching.

I get annoyed when people call it “pension reform” without mentioning that it doesn’t cut pensions, it raises taxes.