Europe’s Dependence on America Is a Choice

And it’s one Europe can afford to undo

I may support trying to convince Greenlanders to vote to become an American territory, but threatening force against Denmark was just insane. Europeans no longer trust the United States. One of the (many) problems for them, however, is that they still depend on America for defense.

Can Europe end that dependence? Mark Rutte, NATO’s civilian head and former Dutch prime minister, says “no.” Speaking to the European parliament:

If anyone thinks here . . . that the European Union or Europe as a whole can defend itself without the U.S., keep on dreaming. You can’t. … If you really want to go it alone, forget that you can ever get there with 5 percent [of GDP spent on defense]. It will be 10 percent.

Is Rutte right? Is strategic autonomy for Europe a chimera, something politically impossible to muster and economically impossible to afford?

I am loath to contradict a former Prime Minister, who also has access to a hell of a lot more information than I do. I’m just a guy, a former E-5, a nobody.

Modesty and disclaimers out there … the evidence is that Rutte is wrong. (Ed West is my witness that I started work on this before the FT ran its article today.) As a citizen of both continents, the possibility of a rupture pains me — never did I imagine that American and Dutch interests wouldn’t align! But here we are, and it matters that Rutte is wrong.

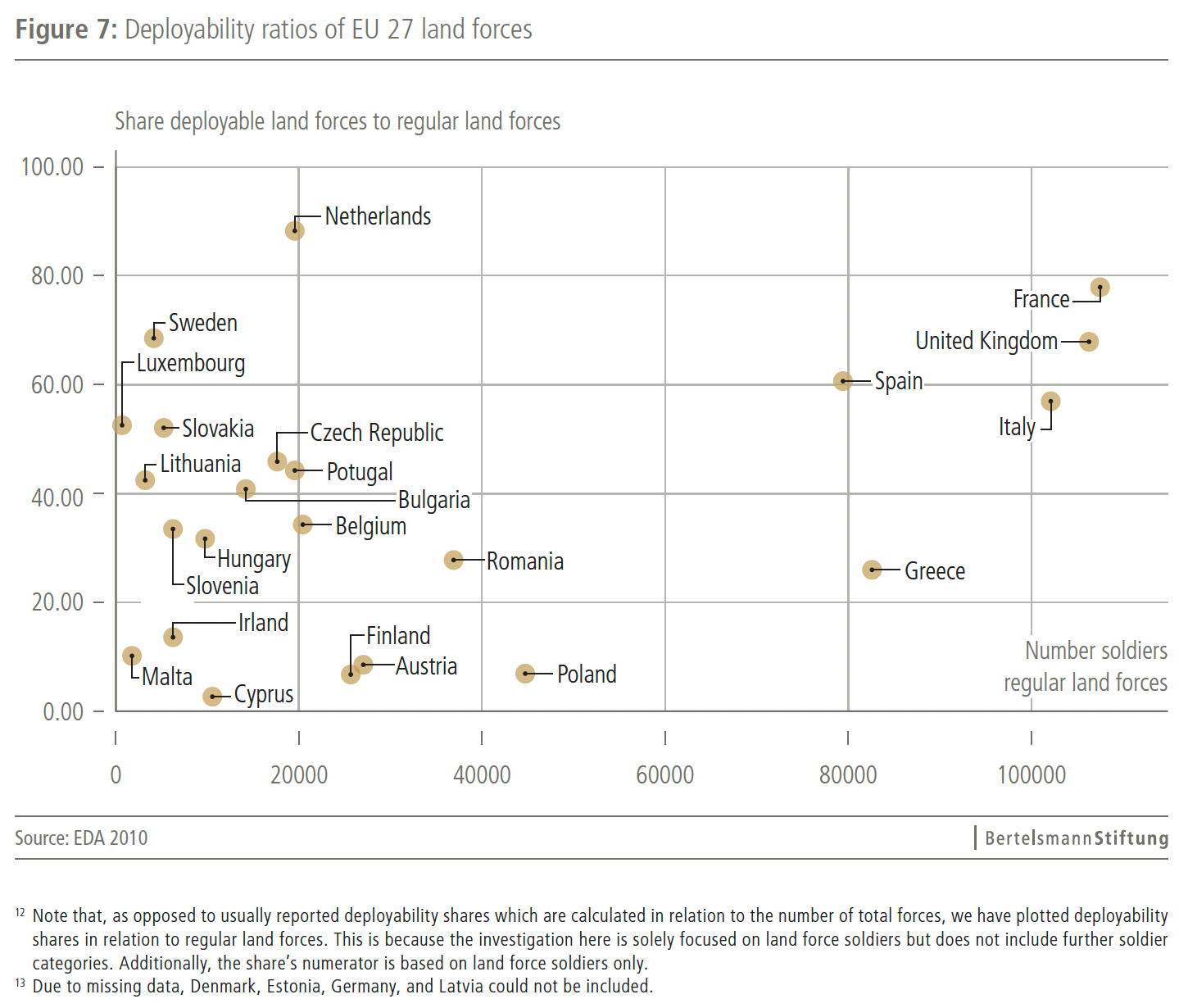

A common European defense will save money

NATO has a common military command and strives for “interoperability”: that is, NATO forces use the same ammunition and power standards and the like. But they are not equipped with a common kit. For example, Europe uses 55 different land combat systems and 39 air systems, as opposed to 5 and 10 for the United States.1 Worse yet, there is a huge variance across countries in the share of their active-duty soldiers who are actually deployable in case of war. This number doesn’t matter much for places like Finland and Poland, which border the Russian Federation, but it makes a big difference for, say, Belgium. (The Royal Netherlands Army, of course, scores very high —although this number may have declined since all Dutch land forces are now effectively integrated into the Bundeswehr.)

Europe could save quite a bit of money by eliminating all the duplication and taking advantage of economies of scale. In 2020, the European parliament commissioned a study that aimed to estimate the potential savings from creating a common military. As shares of GDP and military spending, here are the estimates:

Carlo Cottarelli and Leoluca Virgadamo at Bocconi University doubted this estimate — it’s really large! So the European Parliamentary Research Service later used a more direct methodology and came up with a number that was about half the size, but still large:

To be fair, the second methodology envisioned a less-comprehensive military unification than the first one and limited itself to areas where the authors felt comfortable with the data. R&D, for example, included only “emerging disruptive technologies” in the second estimate, whereas in the first it included things like creating tastier ration packs and redesigning camouflage patterns.

In short, creating a European military would allow Europe to get the same bang for somewhere between four-fifths and three-fifths of its current spending.

Creating new capabilities isn’t that expensive

But Europe also has to create new capabilities if it’s going to free itself from dependence on the Americans. How much would that cost?

Two estimates are floating about, both from 2025. The International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) estimated the capital cost of replacing U.S. combat capabilities, which came to somewhere between €200 and €305 billion. It’s a little hard to convert these numbers into an annual flow, since they don’t include the full life-cycle costs nor personnel costs (they do include munitions), and presumably the flow of expenditures will be lumpy. They end by saying it will cost a cool $1 trillion over a quarter-century, which comes to €35 billion per year.

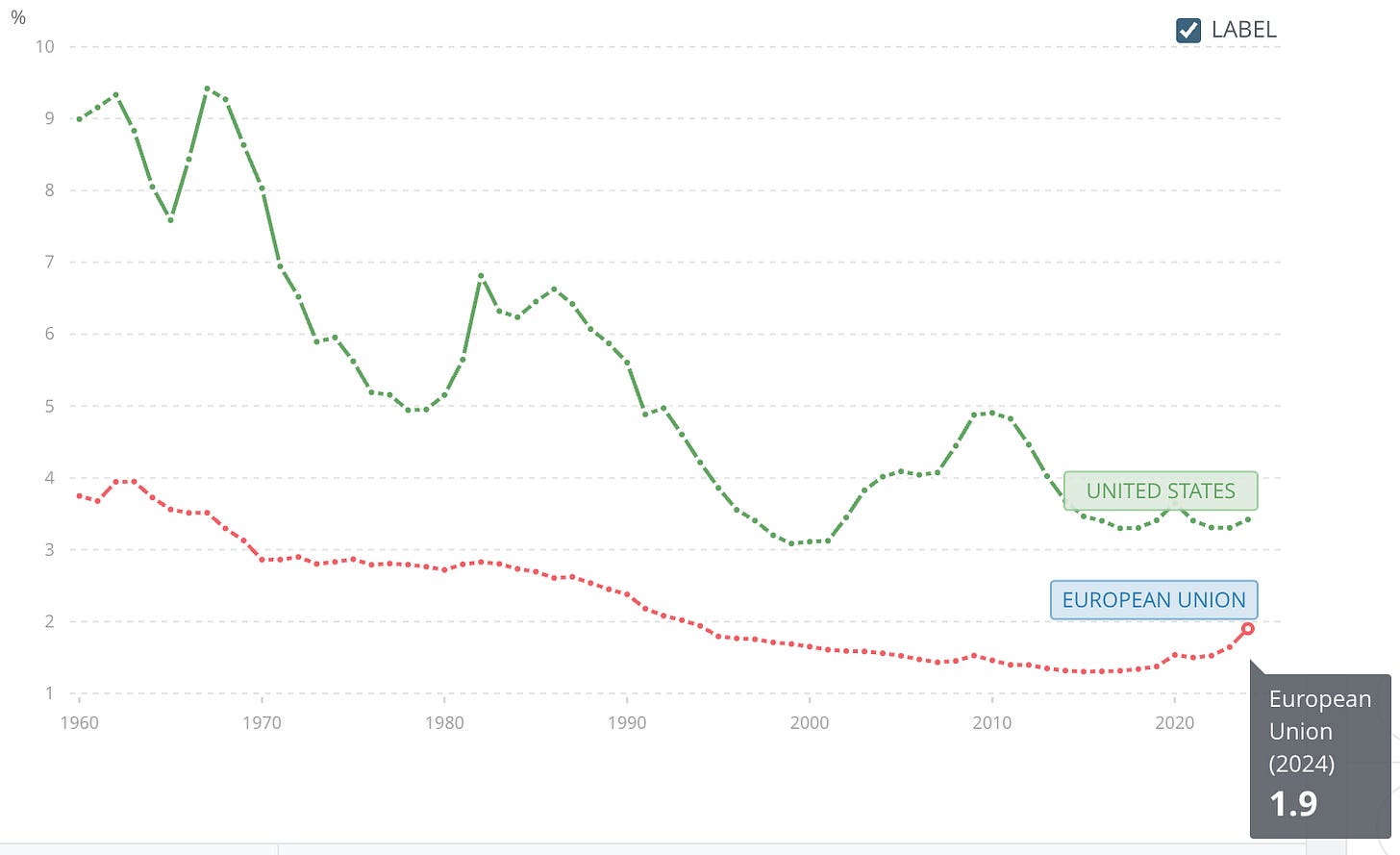

That seems kinda small, actually. No? It’s 0.2% of the E.U.’s GDP, which is almost a rounding error in light of the massive increases in spending that we’re currently seeing. Spending hit 1.9% of GDP in 2024 and is scheduled to head up to 5% in most countries, which by the IISS’s lights should be much more than enough to replicate America’s current sumilitary presence in Europe.

European and American military spending, share of GDP

In short, the IISS’s high estimate of the cost to replicate American capabilities is about the same as the low estimate of what the Europeans could save by getting their act together and creating a common military.

But there’s a problem. This spending is going to be lumpy. There will be short-term spending to rapidly expand land forces and build electric flying robots (the IISS estimate doesn’t reckon with the ongoing revolution in military affairs), but also much longer term projects to figure out how to do things like build nuclear submarines.

Alexandr Burilkov and Guntram Wolff at Bruegel produced a much more back-of-envelopey estimate that it would require roughly €250 billion per year to match American capabilities. That’s a lot more than the IISS! But it nonetheless implies that European annual spending will “only” rise to 3.5% of GDP per year — which if you take the 20% cost savings seriously means that a common European military would only require 2.8% of the Union’s GDP per year.

The problem lies in several vital capabilities … but most of them would probably not be needed to fight off the Russians, or even a Russo-Chinese alliance. The E.U. could certainly use an expanded nuclear deterrent, but the French one is pretty robust, barring some revolutionary increases in the effectiveness of antimissile technology. (Which could happen, of course.) Airlift capabilities will take a long time to rival the U.S., but that’s less than vital in a war against Russia. Space is dicier — as are American intelligence capabilities and our amazeballs “suppression of enemy air defenses-slash-destruction of enemy air defenses” that everyone saw in Venezuela. But you can fight and win a territorial war without that.

Plus American training training training training. Which is not as easy to replicate as people who haven’t experienced it might think.

But building an independent European defense is far from insurmountable, and looks quite affordable, even if it can’t be done quickly.

Political will could change quickly

Right now Europe is increasing defense spending, but there’s not a whole lot of political will to create a European armed force. Oh, the Spanish foreign minister might say that the continent needs a “European army,” but it’s a freaking word salad:

We must go to a European army. I am very much aware that you don’t do that from one day to the other, but if we are doing a coalition of the willing when it comes to security for external threats to Europe, we can very well do it for us, for our deterrence.

Right. We need an army but you know, we can do a coalition of the willing. Huh? At least the French have been direct: European defense would rest upon the sovereign choices of each nation.

Except the French statement is not clear at all either. After all, a nation can make a sovereign choice to merge its military with another nation’s. The Nordic countries have operationally merged their air forces, integrating the chain of command, creating a joint logistics system, combining training, and using similar equipment.2 In December, the Finnish defense minister went so far as to say (assuming you trust the automated translation), “The Nordic air forces will form a unified air force in the future.” They’ve also centralized ammunition production and purchases and created a common field uniform, albeit with separate camouflage patterns.3

And without anybody noticing, the Kingdom of the Netherlands has done just that, quietly merging all of its land forces into the army of the Bundesrepublik next door, despite, uh, checkered historical relations.

Still, those are isolated examples. Why might general European sentiment change?

Well, Janan Ganesh recently wrote a column entitled, “The right will want a United States of Europe.” He said:

The right, above all the hard right, should favour a United States of Europe. And over time, I think it will, at least on the continent, if not in Britain. A unified Europe, a cause that has long been associated with liberals, will start to appeal to traditionalists as the only hope against brash, technologically ascendant superpowers to the west (America) and east (China). It will be framed as a matter of cultural survival.

Ed West agrees, writing:

Right-wing Europeanism is certainly growing, and is based on a real identity, stronger than the post-national ethos that currently defines the E.U. It’s real because, like all strong nationalism, it’s based on a sense of the “other” — Russia and Trump’s America, yes, but more so immigration from the Islamic world.

If they’re right, then the European pendulum might swing quickly in favor of a European military once the older generation of rightists is out of the way, especially if there was a way to build one separately from the current European Union.

One weird trick to create a real European army

Back in the 1950s, western Europe hammered out an entity called the European Defence Community (EDC). The idea was to allow Germany to rearm without creating a German military. Essentially, the treaty would have combined the armed forces of the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Italy, and Luxembourg into the European Defence Forces (EDF), with a common uniform, and then allowed German units to be created under its auspices.

The innovation at the heart of the EDC was the Commissariat. It consisted of nine people appointed by governments but serving fixed six-year terms. The Commissariat would have been charged with signing defense contracts and executing budgets — national governments set budgets and policy, but it was this independent group what would ensure that contracts went to the lowest bidder unless security concerns meant that a single company should get it … which the Commissariat would decide. In fact, the treaty gave the Commissariat authority over all war-related production.

This is heady stuff, more so than the mere fact that national units would be lumped together into multinational divisions. (NATO already does that, just without a common uniform.) And while a common uniform would be pretty cool, it doesn’t mean that much in practice.4 The EDC’s real innovation was the way the treaty made sure that there wouldn’t be any national favoritism in war production and ensured that everything would be standardized and fixed capabilities would be shared in pursuit of a single strategic vision.5

But the French parliament killed it in 1954 — by the expedient of indefinitely postponing discussion rather than voting “no” outright — so in order to resuscitate it, you’d need to go through the whole arduous process of reinventing the wheel by getting all twenty-seven E.U. states to agree. Right?

Maybe not! Here comes the weird trick.

And an Italian legal scholar, Federico Fabbrini, has argued that the treaty is still alive and the ratifications of the four countries that agreed to the treaty are still valid. So all you would need to do to bring it back is get France and Italy to ratify.

Moreover, a resuscitated EDC will have no direct ties to the E.U., which will please many right-wingers who increasingly support European unity but consider the E.U. to be irredeemable. The EDC Treaty makes reference to an Assembly, but those clauses do not refer to the European Parliament.6 The Treaty is also full of references to NATO, which might be a problem if the worry is a bolshy American government. But the references are all conditional — lots of “may” and “recommend” and “with the agreement of.” So that shouldn’t pose a problem.7

It is true that if the revived EDC were to assume by itself the entire burden of recreating America’s European presence, the burden would be a little higher — but still only 2.0% of the combined GDP of the six EDC states, even using the high cost estimate of $250 billion per year. In other words, their defense spending would have to rise from 1.7% of GDP in 2024 to 3.7% of GDP.

Obviously neither France nor Italy is going to bring the EDC back to life today. And as a practical matter, they would need buy-in from Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, even if their parliaments don’t need to take a formal vote.8

But if the political winds shift the way Ganesh (and maybe West?) think that they will, then building a European force will be easier than expected. Once conservatives start to think of themselves as European — driven by the contrast with all the not-European threats out there — then a united Europe as a bulwark against those threats becomes thinkable.

But

I don’t think this will happen. But I think it should. I think it should even if there is a rapprochement between Europe and a future American administration. The math adds up, the threats are real, and the management problems were sorted out in 1954. Just do it!

Marco Centrone and Meenakshi Fernandes, “Improving the quality of European defence spending — Cost of non-Europe report,” European Parliamentary Research Service (November 2024), p. 4.

They have converged on the F-35 over the Gripen, which might cause problems if the U.S. and E.U. really do break. This problem is explicitly discussed at 4:38 in the video. “These jets may be the last American aircraft Denmark acquires for a while.” Sweden is moving from America to Brazil for transport aircraft; others will follow.

To be honest, I don’t believe that the different patterns are really any more effective. This is residual nationalism. Ironically, given current events, Denmark’s pattern is almost indistinguishable from the U.S. Army.

As the Dutch soldiers who have all found themselves effectively serving in the German army will tell you — your German commander doesn’t care that you’re wearing a different uniform. The different command styles can cause teething pains, however. In 2023, the highest-ranking officer in the Royal Netherlands Army told Parliament: “If a German commander takes a decision, it is the end of the discussion. When a commander takes a decision in the Netherlands, it is the start of a discussion. But we have to respect each other.”

NATO tries, but doesn’t succeed at that last bit.

They refer to the Assembly created as part of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), and that treaty expired in 2002. The Treaty calls for a conference to replace the ECSC Assembly with a new democratic body, and then says “if the Conference … has not reached an agreement within one year … the member states shall by agreement among themselves proceed to a revision of the provisions [governing the Assembly].” Moreover, the Assembly only has limited veto powers under the treaty, which is designed to function fine without it.

The EDC Treaty contains provisions to insure its continuity if NATO ceases to exist.

In theory, France and Italy could revive the treaty, only to have Germany say, “Hey, we didn’t mean it, not gonna participate” but since activating the treaty only requires six ratifications then the EDC could go along without Berlin. In practice, even I can’t imagine that happening.

Brilliant breakdown of the actual economics here. The 0.6% GDP savings figure from eliminating redundancy in procurement and standardization is huge when most debates ignore that angle entirely. I've worked adjacent to defense logistics and the waste from 55 differnet land combat systems versus just 5 is insane when you consider maintenance chains alone. What strikes me is how Rutte's 10% claim assumes zero efficency gains which seems almost deliberately pessimistic.