Was Napoleon right? Thoughts on the Chilean constitutional draft

“A constitution should be short and obscure”

Today, Chile votes on a new constitution. We think it will be better if Chileans vote it down. But we do not think that for the typical reasons: the prose is bad, the tone is too woke, the policy commitments are left. Those things are all true, but they are mostly superficial. Rather, the problem with the new constitution is that it is a bad governing document. If enacted, Chile will become more like Brazil, or, God forbid, the United States.[1]

TLDR: the new constitution will hamstring the Chilean state and make it extremely difficult for governments to get anything done in a country that still needs to get things done. Sure, political paralysis can afflict countries with streamlined constitutions — look how the U.K. has saddled itself with a housing crisis for no good reason — but it almost always afflicts countries with clunky veto-ridden messes. And a clunky veto-ridden mess is what Chile has produced.

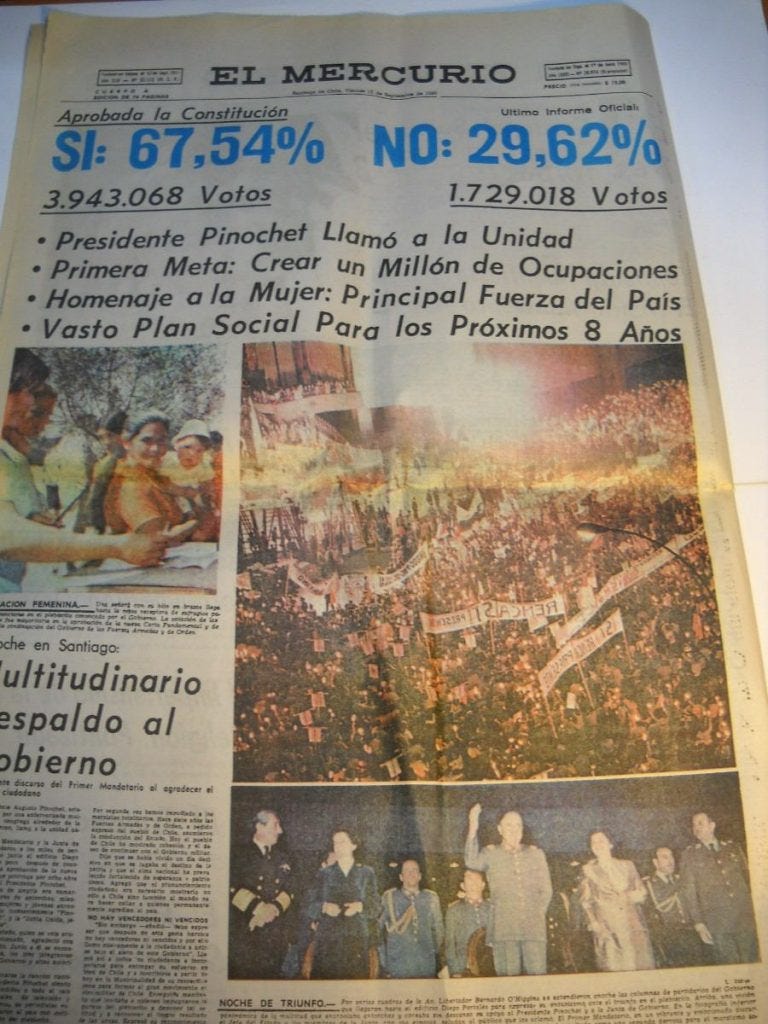

Before we start, we should point out that the problem with the current constitution is legitimacy. Substantively, it is a fine governing document with no particular political valence. That was not always true. In 1980, when the dictatorship wrote it, the constitution was a dictatorial authoritarian mess. And as a general rule, as Michael Albertus and Victor Menaldo (U.W.) have shown, holdover constitutions generally work pretty badly when democracy returns! But the 1980 constitution was relatively easy to amend and most of the offending clauses were removed over the subsequent decades. By the time the 2019 riots rolled around, there were only four significant flaws, none of which was particularly egregious and only one of which has any particular ideological valence.[2] In other words, the problem wasn’t anything in the current constitution; it was that the current constitution was imposed by a brutal dictatorship that killed and tortured and redistributed income from poor to rich. (See page 265 here.)

OK, so what’s wrong with the new document? Let’s briefly go over some of the common objections which we think are not that serious.

1. Polarizing wording: The new constitution’s phrasing is deliberately provocative to anyone of mildly conservative sensibilities. That said, there isn’t really any way to write a gender-neutral document in Spanish without offending some people’s sensibilities, and just because something annoys you is not a reason to reject it.[3]

2. Length: The document itself is long, around 54,000 words. Still, many countries have overly long constitutions without too many problems. For example, New Zealand’s governing documents come to 48,438 words while Austria’s constitution is a prolix 41,366 and both places seem to do okay.

3. Torturous prose: The Constitution is repetitive and desperately needed an editor. The Convention refused to appoint one because that would be authoritarian. There was a 40-person editing committee, which did about as good a job of editing as you would expect a 40-person committee to do. They cut the draft from 499 articles to 372, which then somehow expanded back up to 388 articles on the Convention floor.[4] The writing really is terrible and confusing and overwhelming and one of us is a native Spanish speaker! Still, while repetition and length are annoying, they also aren’t particularly harmful.

So what is the serious problem? Too many opportunities to gum up the wheels of government. It’s great the constitution eliminates the mostly-terrible Chilean senate! But it adds too many other roadblocks for us to support it.

The clauses that most worry us are in Articles 153-57, where the constitution calls for referenda. Article 157 allows three percent of the population to force a legislative proposal onto Congress’s agenda. Article 158, conversely, allows five percent of the population to call a referendum to repeal any law that doesn’t involve taxation or budgeting. It is very easy to see how these could be used to obstruct legislation. More seriously, Article 155 calls for municipal and regional referenda on any topic, which will turn the country’s newly empowered regional governments into sclerotic messes.

Other clauses introduce further sand into the governing process. Article 152 calls for public reviews and comment periods for legislation. Such provisions create opportunities for lobbyists — in other countries, they are the ones who make most of the “comments.” They also open the door to legal challenges based on procedural problems. Articles 191 and 192 mandate popular participation in regional policy making, which will further hamstring the regional governments. Articles 58, 59 and 143 set the stage for fights over water resources.[5] Article 333 creates a system of special environmental courts. Article 119 makes it much easier to sue the government for failing to meet its constitutional mandates. Finally, a series of vaguely-worded clauses about new indigenous governments open the door to indigenous vetoes over large-scale infrastructure or energy projects.[6]

In short, we worry more clauses designed to reproduce the procedural excesses of Anglo-American democracy more than we worry about a long laundry list of positive rights. The latter is something that is common to many constitutions across the world. (Have you read the New York State constitution?) We do not think that such lists are a good thing, but we can say that scholars have found no causal links between constitutional guarantees and more social spending.

On the other hand, procedural roadblocks have pushed the United States and Great Britain into slow-motion crises. Neither country can build long-distance power lines or infrastructure projects; increasingly, they can’t even build solar power plants or large wind farms. Both countries have created housing shortages for no good reason, despite slowing population growth and (yes, even in Britain, which is only half as densely populated as New Jersey) an abundance of open space. A decade ago, one of us was impressed by Chile’s ability to build … that ability could be lost while the country still desperately needs it.

Napoleon was right for the wrong reason: “A constitution should be short and obscure.” Otherwise you get a structure that’s too rigid for good governance.

The last thing that Chile needs is to make governing more difficult than it already is.

[1] The fact that the U.S. managed to saddle itself with the problems that we lay out using a short and succinct governing blueprint and a concise Bill of Rights indicates that we are not worried about problems of tone or length.

[2] The strange clause on “constitutional organic laws.” Those are defined as laws that carry out constitutional mandates and they require a four-sevenths supermajority. The bizarre result is to make it harder to implement any rights or mandates written into the current constitution.

[3] The drafters weren’t consistent in their decisions. For example, the Convention decided that some words ending in “e” are masculine and therefore must be presented twice: “Presidenta o Presidente.” But they also decided that other neutral e-words did not require such treatment, so we get only “Representantes.” Uh, okay.

[4] For all our criticisms of the final version, Tammy Pustilnick deserves credit for doing a much harder job than Gouverneur Morris had to face. If you want to see how the Convention made decisions in all its gory detail, go here. In case of link rot: Diario Oficial de la República de Chile no. 43,076 (13 October 2021), pp. 1-31.

[5] Article 58 guarantees indigenous nations the use of water resources in their territories — which have not been delimited. Article 143, meanwhile, mandates a “participative and decentralized system of water management,” which would open whatever system Congress decides upon to serious litigation.

[6] Article 234 and Article 309 are the main ones, but similar clauses are scattered throughout the text.