Observatorio argentino 46: All this will PASO

Argentina has a weird two-stage electoral system. The first stage is called the PASO, for Primaria Abierta Simultánea y Obligatoria. Everyone has to vote in the primary, therefore “Obligatoria.” (Although the fine is currently running only around 50¢, U.S.) All parties are on the ballot, thus “Simultánea.” Any voter can vote for any party, thus “Abierta.”

Yesterday was the PASO! All votes have been hand-counted and the results are in, which should make all Americans slightly ashamed.

In the senatorial PASO, each party puts up two candidates in each province. If a party has internal competition, then it puts up more than one slate. (Most parties put up only one slate.) If you get more than 1.5% of the vote in the PASO and beat the competing slates within your party (if any), then your slate gets on the ballot for the general election. When the general election comes along, the party with a plurality of votes will win two Senate seats for the province and the runner-up will get one. If that seems like a stupid system to you, that is because it is, although stupidity is a general characteristic of most senates around the world.

The PASO for the lower house runs similarly. Each party puts up a list of candidates, ranked in order. The lower house of Congress is based on proportional representation, so if a province has (say) 35 seats, then the party needs to put up a list of 35 candidates in the order in which they will take their seats. In the PASO, a slate has to clear 1.5% of the vote and beat any competing slates in order to get on the general election ballot. When the general election rolls around, seats will then be distributed to the winning party based on their vote share. So if you win, for example, 15% of the vote share in Buenos Aires in the general election, then the first 5 names on your party list get to go to Congress.

What is voting like? Well. You go into a polling station. There you wait in line, match your name to a voter registration list, and get a ballot. Which looks like this for the lower house in Buenos Aires province:

I told you that there were a lot of parties here. The photo (if there is one) is of the headliner(s): that is, the first person on each party list. You can see that Juntos por el Cambio (Together for Change) and the Frente Unión por el Futuro (United Future Front) conducted a genuine primary. For the former, you had to pick between the slate led by Diego Santilli and the slate led by Facundo Manes.

The rest of the parties fielded only one slate, so the only thing that they had to do was clear 1.5%.

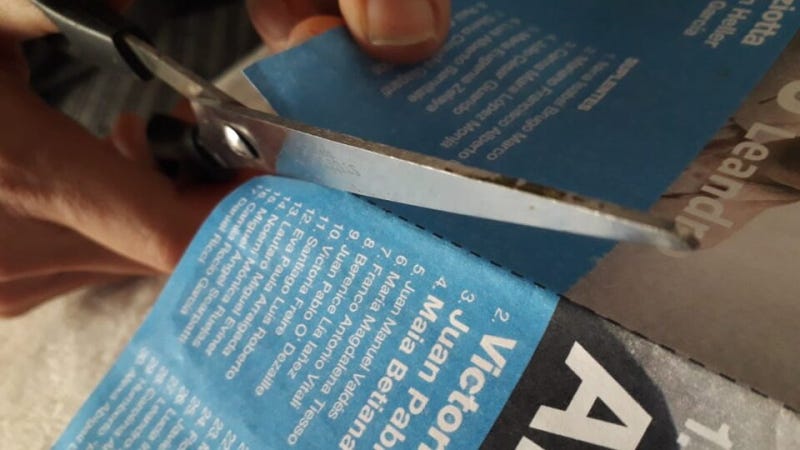

You might ask upon seeing this ballot, “WTF?” I certainly did back in 2019, when I visited a polling place in San Isidro, B.A. Well, here is the F. Polling officials give you a pair of scissors. You go into a little private booth. You then cut out your preferred party list, stuff into an envelope, properly seal the envelope, and then put the envelope into the ballot box.

In general, the PASO is nothing more than a government-sanctioned obligatory poll. The parties do not have to allow for competing slates if they do not want to. Juntos wound up fielding two slates because it is not really a party. Rather, it is a coalition between two parties who usually hate each other: the Radical Civic Union (UCR), which has long historic roots, and the Republican Proposal, which dates back only to 2010 and started as a personal vehicle for Mauricio Macri.

(As for the Frente Unión por el Futuro, well, I have no idea why they fielded two slates. Neither one cleared 1.5%.)

Anyway, as a government-sanctioned obligatory poll, which is highly correlated with the general election results, the PASO has the ability to move markets and break careers. So what happened yesterday? Well, you will have to either go to any other news source of the hundreds available to you ... or wait until tomorrow.